https://triblive.com/opinion/carl-p-leubsdorf-republicans-hope-the-supreme-court-will-help-them-hold-the-house/

Carl P. Leubsdorf: Republicans hope the Supreme Court will help them hold the House

Perhaps it was inevitable.

But it seems increasingly likely that the Supreme Court, with its 6-3 conservative majority, will play a major role in determining which party wins the U.S. House next year.

That possibility increased when Justice Samuel Alito paused a lower court’s rejection of the effort by Texas Republicans to heed Trump’s demands by giving themselves five more House seats.

With filing opening Dec. 8 for the 2026 Texas primaries next March, the full court’s ultimate ruling will either restore the GOP effort to use redistricting to keep its House majority — or doom it.

But Texas is just one of several states whose redistricting cases could ultimately wind up before the court. That includes some where GOP-controlled states joined Texas in voting to help the Republicans — and others where Democrats sought to offset them.

This legal maneuvering is occurring against a political backdrop in which polls indicate that, without judicial intercession, voters are increasingly likely to restore Democratic control of the House next year — and thus dampen the final two years of Trump’s presidency.

But the potential for judicial influence goes beyond the rush to redistrict.

The justices are also considering a case that could dramatically change the entire legal basis for redistricting by overturning 60 years of rulings that the 1965 Voting Rights Act requires that minority voters have an opportunity to pick representatives of their choice.

With Republicans currently holding only a three-seat House margin, and the political tide running against them, the prospect of favorable Supreme Court rulings may constitute their best real hope of keeping control.

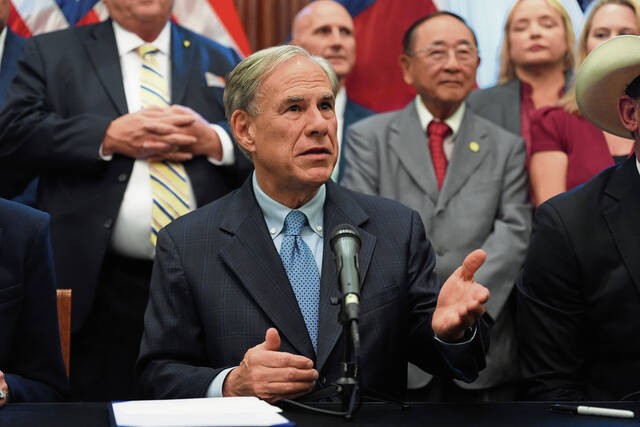

This latest skirmish began when Trump pressured Gov. Greg Abbott and the Republican-controlled Texas Legislature to enact an unusual mid-decade House redistricting plan to help the GOP buck a potential 2026 Democratic electoral tide. The goal was to increase the party’s current 25-13 margin by five seats, though reduced GOP support among Hispanic voters in recent polls and off-year elections has raised doubts that will happen.

But the GOP plan suffered a judicial setback earlier this month, ironically in a decision written by a Trump appointee. A three-judge federal court ruled the Republican redistricting plan was unconstitutional because it was racially discriminatory, rather than the kind of political gerrymander that the court previously sanctioned. It would likely eliminate the seats of two Black Texas Democrats and make three other districts more Republican.

The decision cited a letter from the Trump Justice Department that contended the state’s prior 2021 districting plan reflected illegal racial considerations, even though it followed Supreme Court guidelines.

After the Texas legislature’s action, the Missouri legislature’s GOP majority voted to eliminate one of the state’s two Democratic House members, and Ohio Republicans passed a plan that could cut 1-2 more. Further Republican moves are pending in Florida, but reluctant Republicans blocked potential action in Indiana and Kansas, at least for now.

Unsurprisingly, those moves prompted Democratic responses, notably Gov. Gavin Newsom’s plan to add five Democratic seats in California, which its voters approved this month. A state judge unexpectedly gave Utah Democrats a seat they can likely win, and Virginia Democrats could easily add two more early next year.

Republicans quickly filed a court challenge to the California plan. Interestingly, their suit opposing the Democrats is backed by the same Justice Department that is supporting the GOP’s Texas plan, lest anyone doubt this is more about politics than legalities.

Meanwhile, the Supreme Court itself has raised doubts on the future role of racial considerations in congressional redistricting. Earlier this month, it held a re-hearing on a much-debated case involving the drawing of district lines in Louisiana.

In that case, it ruled last year that the Voting Rights Act required the state to create a second minority majority district — out of six — because Louisiana’s population is more than one-third Black. But critics of that decision argued this month that the landmark law’s provisions protecting minority voters should be declared illegal because they discriminate against white voters.

Several members of the court’s conservative majority — which includes three Trump nominees — seemed sympathetic to that argument during the oral argument. If the court ultimately rules that way, the practical result would be to enable Republican legislatures in Southern states to eliminate districts that have generally elected Black Democrats, possibly jeopardizing the re-elections of more than a dozen of them.

There is a certain irony in how Trump, who has contended without evidence for years that the 2020 election was rigged against him, now wants to rig next year’s congressional balloting for his party.

It’s because the Republicans fear the combination of the normal mid-term tide against the party in power, Trump’s low job approval levels and the party’s tiny current margin is likely to bring a Democratic House — unless they could change the calculus. Recent polls confirm their fears.

Not only would a Democratic House stalemate any Trump legislative initiatives, like proposals for further domestic spending cuts, but it would almost certainly unleash a spate of investigations into his administration and probably, given recent history, renewed attempts to impeach him.

After all, when Trump was last in the White House and Democrats regained the House in the 2018 midterm election, he was twice impeached by the House — though rescued both times by the GOP Senate.

Republicans hope the Supreme Court can help to prevent that.

Copyright ©2026— Trib Total Media, LLC (TribLIVE.com)