The City of Pittsburgh’s Bureau of EMS (Emergency Medical Services) Medic 5 is located at the border of two vastly different neighborhoods. One, Oakland, is home to the University of Pittsburgh, two major hospitals and a busy business district. The other, the Hill District, is a historically black community that has significant problems with violent crime and poverty. I started my Pittsburgh EMS career at Medic 5 as a paramedic student and eventually ended it there as a crew chief.

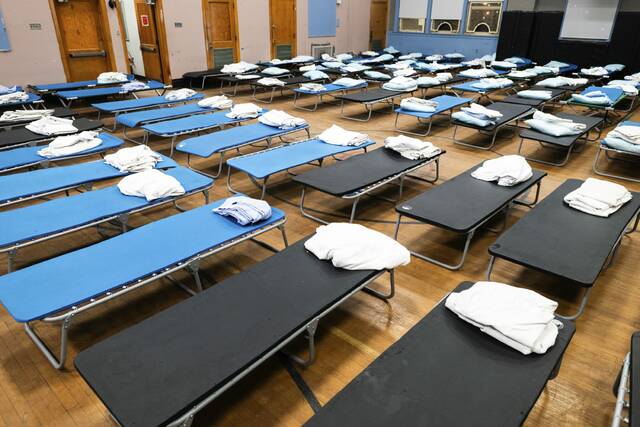

On Friday nights, the general inclination would be that most of Medic 5’s time would be spent in the Hill District. However, it was much more common for the university to overwhelm the system, with its intoxicated undergraduates sometimes using five of the 10 available ambulances the city had in service on any given night. Given that the system was already strained due to understaffing and overutilization, taking valuable resources to transport mostly non-taxpaying, non-city residents to a hospital blocks away did not sit well with most of the paramedics.

To make matters worse, Pitt and UPMC, the organization that owns the two hospitals in Oakland, are both nonprofit institutions, meaning that they do not pay property taxes on any of their significant amounts of property. According to City Finance Director Paul Leger, this means about 40% of the assessed property value of Pittsburgh is untaxed. This is especially fiscally damaging because local governments are highly reliant on property tax revenue. As the industries of many American cities, especially in the Rust Belt, change from manufacturing to health care and education, local governments need to find a way to receive revenue from these institutions that own a significant amount of valuable property and put a significant strain on city services.

Historically, cities have attempted to do this through PILOTs (payments in lieu of taxes). These are voluntary payments made by nonprofit institutions instead of paying property taxes. PILOTs are negotiated between the locality and the institution and vary widely, and they are often unequal and unreliable.

One city has been able to provide some consistency in its PILOT agreements. Boston is best known for Harvard, Tufts University and the Red Sox, similar to Pittsburgh with Pitt, UPMC and the Steelers — two of which, in both cities, do not pay property tax. However, Boston created a PILOT Task Force to negotiate payments. The task force includes representatives from all stakeholders and created a systematic approach to how much is paid and who pays PILOTs.

Boston’s program has a few features. First, it has a $15 million property value threshold to determine which nonprofits to request PILOT payments from, thus excluding smaller organizations. Second, a target for contributions is set based on the cost of services that directly benefit the nonprofit. Third, a set rate, based on a measurable metric like revenue, is used to further justify and equalize payments.

Municipalities also can allow nonprofits to reduce or make their payments by providing services to residents. This is something nonprofits are often well equipped to do. However, municipalities need to be clear and consistent about what services are needed and which will qualify. Finally, long-term PILOT agreements are best. Long-term agreements allow municipalities to spend less time on negotiations and make better budget predictions.

PILOTs are still voluntary payments, and they are unlikely to adequately satisfy the revenue lost by tax-exempt property. Municipalities should therefore look to other means to gain revenue from nonprofits. One option is more fee-based funding of services such as fees for garbage pick-up, snow plowing or sidewalk repair, instead of these services being tax funded. Another example would be the ambulance response mentioned above. Although operationally it had a lot of cost for the bureau, fiscally it potentially works well. College students, compared to low-income residents of the city, were usually much better insured and, since they were not typically city residents, they were held responsible for ambulance bills.

As city economies transition to a greater reliance on nonprofit organizations, local government needs to find a way to recoup revenue lost from the increasing proportion of tax-exempt property. However, unlike the factories of the past, universities and hospitals are much less mobile and more reliant on the municipality for their image. It is therefore in their interest to be located in a successful, well reputed city. This gives hope to the residents of Pittsburgh that health care and academics could become more fiscally sustainable than steel and coal.

Charles Pratt is a University of Pittsburgh alumnus and former Pittsburgh paramedic. A police officer in Madison, he is pursuing his master’s degree in the University of Wisconsin’s La Follette School of Public Affairs.