“Life is full of a thousand red herrings, and it takes the history of a civilization to work out which are the red herrings and which aren’t,” once noted Welsh screenwriter and film director Peter Greenaway.

Or a public policy think tank that condenses the long history of facts to dispel one giant canard in one deft swoop.

As the debate continues in Harrisburg about how to fund public transit, the issue of geographical funding equity has reemerged. That is, shouldn’t rural areas help foot the bill for urban public transit services?

After all, one local newspaper columnist argued last month that “every dollar put into mass transit generates up to five … dollars in economic activity.”

“But that hasn’t stopped state senators from rural counties from arguing against funding Pittsburgh Regional Transit (PRT) and Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA), claiming it harms rural communities,” the columnist wrote.

“Even though urban taxes subsidize rural roads, hospitals, police departments and other crucial public services,” she argues.

But this red herring has been around for a long time, notes Alex Sodini, a research associate at the Allegheny Institute for Public Policy (AIPP).

He cites a 2013 AIPP analysis (Policy Brief Vol. 13, No. 33) that evaluated testimony from the Greater Pittsburgh Chamber of Commerce and the Allegheny Conference on Community Development provided to the Pennsylvania House Transportation Committee, which attempted to persuade rural lawmakers to approve funding for mass transit.

“The testimony insinuated that rural roads and bridges were ‘built and maintained with gas taxes from Philadelphia and Pittsburgh and other urban areas around the state,’ and therefore ‘rural counties should be willing to move funds to urban areas to fund mass transit,’” Sodini recounts.

But that research, from 12 years ago, concluded that the primary methodology to reach that conclusion — juxtaposing the number of urban vs. rural linear miles — was weak.

“In sum, linear miles of road are not the sole determinant in road funding, and, in fact, urban areas likely have a leg up based on the existing formulas,” Sodini says. “Even before factoring in a variety of other funding sources at the federal, state, and local level — the idea that urban gas tax money is being diverted en masse to support rural roads is not so clear-cut.

“Consequently, using such a claim to justify mass transit funding is dubious at best,” he says.

“As was the case a decade ago, the debate over which taxpayers should subsidize others’ transportation interests misses the point,” Sodini says, noting that Act 89 of 2013 was the last attempt at a comprehensive transportation funding package. But as Policy Brief Vol. 13, No. 59, noted: ‘while (Act 89) raises considerable funds for roads, bridges, and mass transportation it falls woefully short in demanding accountability for the money.’”

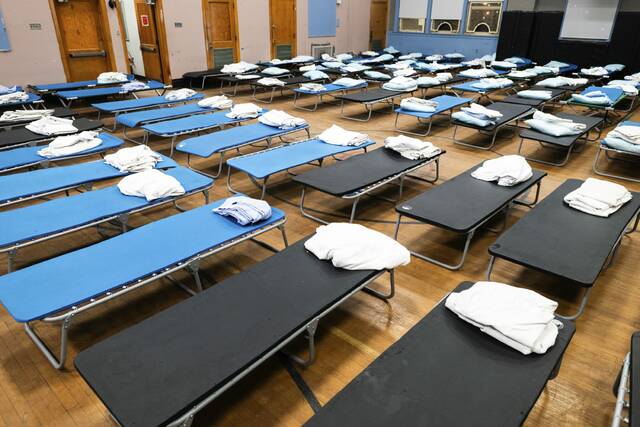

Think of, as but one example, the Allegheny Institute’s well- and oft-documented PRT exorbitant bus operating expenses per vehicle revenue hour (VRH), the fundamental cost of providing the service.

“Data from the National Transit Database showed PRT’s fixed-route bus service ranked sixth-highest in the nation on operating expense per VRH,” Sodini reminds. PRT’s bus operating expense per VRH dwarfed the nine other agencies included in its ‘peer agency selection’ in its annual service reports.

“Additional measures to ensure accountability and efficiency for mass transit agencies would be a step in the right direction,” he says, “but more substantial reform is needed. Although it wouldn’t deal with existing legacy costs, eliminating the right of transit workers to strike must be the first priority to help lower future expenditures,” Sodini says. “Privatization and/or contracting out are hinted at in (new state legislative proposals) but must be more seriously explored, if not mandated.”