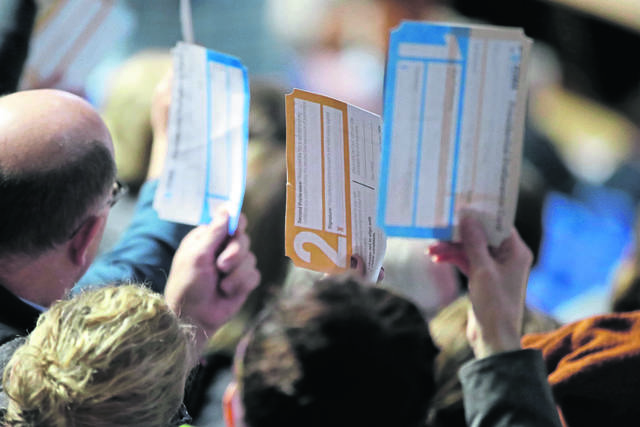

During Monday’s Iowa caucuses, a mobile app designed to report results malfunctioned. Unsurprisingly, Republicans gloated that the glitch is a calamity for Democrats.

Yet even The New York Times worried about what this snafu might signify. As Times columnist Frank Bruni wrote, “Maybe there’s a moral here in dreaming too big and reaching too high.”

Bruni is on to something.

Innovation isn’t as easy as it appears. We take for granted not only decades-old marvels such as automobiles and antibiotics, but even newer wonders such as smartphones and music streaming. These and countless other embodiments of innovative awesomeness are so commonplace that, by the time they reach us as consumers, they seem routine, even easy.

But there’s nothing easy or routine about successful innovation. The innovations that we see all around us appear easy — indeed, almost natural — only because they’ve been tested and polished in highly demanding free markets.

Free markets have four vital features that call forth innovation in ways that make its fruits appear to consumers to be mundane. The first is the fact that entrepreneurs spend only their own money or money voluntarily entrusted to them. The second is the freedom of whoever wishes to compete for consumer dollars to do so. The third is the freedom of consumers to buy, or not to buy, whatever products are offered for sale. The fourth is the resulting competition that rewards with profits innovators who please customers and penalizes with losses innovators who don’t.

Each of our modern marvels is the result of human creativity tested and improved in markets. From innovations in transportation and packaging that enable Bostonians to enjoy fresh blueberries in January, to advances in electronics and computer technology that give us online retailing and sharing-economy apps, these innovations are overwhelmingly the product of decentralized free and competitive markets. By the time we consumers see innovations and their fruits, the failed ones have been weeded out and the successful ones are much improved from their original state.

As the Iowa caucuses show, not all innovations work. This particular failure is more visible than most only because of the high profile of U.S. presidential elections. And so while Democrats should not be ashamed of this failure, it ought to teach them the importance of humility.

Today’s Democratic ranks swell with people armed with plans and blueprints for using government to overhaul or re-engineer large swaths of the economy. These plans, all born of hubris, are fun to discuss, and the blueprints are exciting to ponder. Yet this sort of policy innovation is not tested by market competition. Government imposes these schemes on citizens, and no politician or bureaucrat — unlike a private entrepreneur — has a personal financial stake in getting things right.

If a President Sanders’ plan for making college more affordable fails, his personal wealth won’t decline. Indeed, he’ll still likely receive plaudits for his good intentions. Ditto for a President Buttigieg’s blueprint for increasing the affordability of health care. The people who will bear the costs of these interventions if they fail are ordinary Americans.

Making matters worse is that failed government programs — unlike the Iowa debacle — don’t often reveal themselves as failures. Compelled to pay and participate in programs, citizens can’t easily express their dissatisfaction. Costly and damaging programs often survive.

I hope against hope that Democrats will learn from their Iowa experience that if engineering a new app is subject to failure, the successful engineering of society is impossible.