When the virus struck, we were terrified. We saw people dying alone on television. Confused about how the virus spread, we washed groceries and hands repeatedly, changed our clothes and immediately modified our work. For me, that meant seeing my patients online. This felt heretical, because I’ve always sat with the patient’s pain — literally — to facilitate emotional healing.

My method was altered dramatically. So was my way of communicating with my oldest male friends. The four of us went to college together 40 years ago and have been close ever since, with ebbs and flows. Some friendships were challenged by career moves. One friend’s depression eight years ago and our frequent conversations about his moods brought us closer.

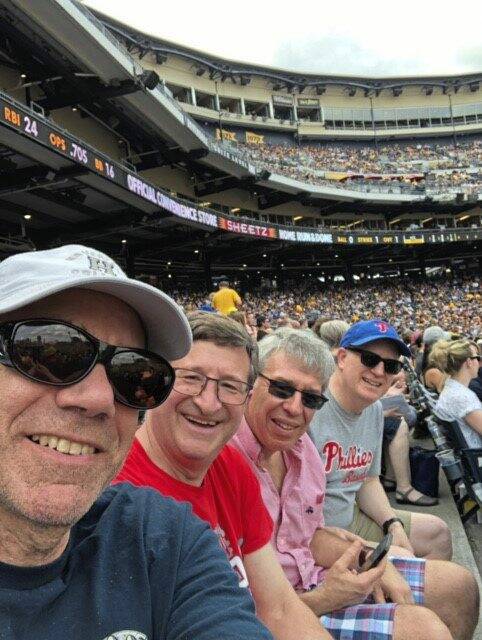

Because we live in different parts of the country, regular in-person contact had become impossible. We dealt with these limitations by traveling annually for long weekends. Since we love baseball and its timeless rituals, we agreed about 10 years ago to visit ballparks in a different city each year. Chicago, Pittsburgh, New York, Baltimore, for example, with Toronto planned for 2020. But what happened instead has been a golden lining.

In the spring of 2020, springing from covid upheaval, we began to meet every Sunday for Zoom conversation. We overcame the muted volume and blank windows with input from our kids. And we began to talk with continuity about some of the travails about which we had fallen out of touch: our careers, their triumphs and disappointments; concerns about our health; our kids’ decision-making as they navigate an overwhelming number of variables; worries about our aging parents; and most important, exasperation with our cherished baseball teams. Yes, men can talk about feelings if the environment is secure.

We benefited from the momentum that builds from weekly meetings. Subjects could be extended and deepened from one conversation to the next. Being able to see each other helped; when one friend contracted covid, we were reassured to see that he wasn’t short of breath. Our relatively small number of four means that we take turns talking and listening; if someone is silent for too long, the others notice and ask: are you OK?

The truth is that baseball wasn’t most important. What took priority was our anxiety about the status of the country. As a professional group leader and student of group dynamics, I wondered whether this emphasis represented avoidance of tender personal matters. Or was it the result of our already knowing each other’s quirks? No, actually, I think it reflects our place in the lifespan: late middle-age, most of our children almost launched, awareness of mortality, wondering how we can leave this earth intact and slightly better.

The problems have accumulated while potential solutions have been blocked. The climate will not cool down without planetary coordination. The inequities in our society are blatantly wrong. We are incredulous that citizens can’t agree on values of fairness and reality. That not everyone agrees our community should begin with looking out for our neighbors and not ourselves. Some can’t agree that vaccines are a safe godsend. That public officials’ lying should be unacceptable and grounds for removal. No, our citizenry can’t agree on these principles.

We think about our group of four and how we have jelled during the pandemic. How are other small groups faring? The crucial determinant is a concept called group attachment security, which is essentially how accepted and protected you felt in your family of origin. When people are alienated within their families of origin, they search with urgency for new groups where they can find a sense of belonging. Sometimes this works out. Sometimes it doesn’t and they remain alone. Sometimes people join groups where there is no room for dissent.

We don’t agree on everything. One of us is cynical about the likelihood that our society can tackle these problems. One of us would dissolve capitalism. One of us would shackle drug companies. But we disagree respectfully. We are straight with each other when we mess up. We consult with each other about dilemmas regarding our families. If one of us is in trouble, the others will undoubtedly be there. This is a unique kind of love and we all know it.

Would it have evolved this way without the pandemic? We would have eventually resumed our trips to watch the Mets lose. But for all of my reservations about the acceleration of technology, it allowed me to treat patients during those months and the four of us to draw closer. I treasure these friendships, and in a world increasingly less connected, we should strengthen our relationships any way we can.

Andrew Smolar, M.D., is a psychiatrist, psychoanalyst and clinical associate professor of psychiatry at the Temple University School of Medicine.