Trials should happen as soon as possible after the defendant is arrested.

The U.S. Constitution spells this out in the Sixth Amendment, the first of several rights afforded.

“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial, by an impartial jury of the State and district wherein the crime shall have been committed,” it states.

A speedy trial might seem like a license to lynch, but those other rights — a right to counsel, a right to confront witnesses, a right to be told the charges — should counter that. They should ensure a quick trial is a fair and well-represented one.

But while the founding fathers — men who had recently committed treason to create the country — were no doubt concerned about the rights of the accused, those same rights protect the system. By defending the integrity of the court, they also stand for victims.

Following the rules of jurisprudence means a case is less likely to go wrong, to be overturned on appeal or to make victims and witnesses endure retrials. But does a speedy trial help anyone other than the defendant?

Yes, it can — because when someone doesn’t get to court in a timely manner, it can affect the outcome.

In May 2015, Tionna Banks and her grandmother, Valorie Crumpton, were killed in Crumpton’s East Hills home. It was a gruesome crime. Banks, who had recently had a baby, was stabbed 15 times. Her grandmother was bludgeoned with a fireplace poker.

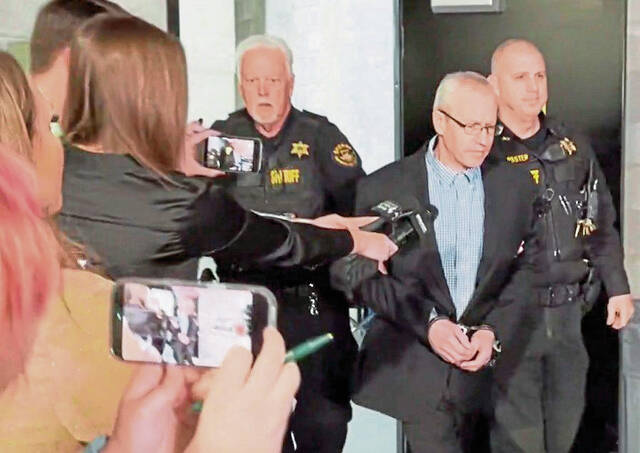

Solving the crime was not a complex math problem. Banks had a restraining order against Cesar Mazza for an assault during her pregnancy. Mazza was arrested in August 2015.

Pennsylvania’s Rule 600 compels criminal cases to go to trial within 365 days for a defendant on bail. For someone incarcerated such as Mazza, the threshold is six months. That can change if the defense requests delays or prompts delays.

But Mazza is pleading guilty more than 10 years after being charged. In a plea deal struck without input of the victims’ family, Mazza is set to plead to an Allegheny County judge. In return for removing the death penalty, Mazza would receive a sentence of 30 to 60 years in prison for both murders. With credit for the decade he already has been jailed, he could walk free in 2045 at age 57.

The slow walk to a sentence did not just take a first-degree capital murder case and reduce it to a third-degree homicide. It also happened without consultation with the family of the victims.

Robin Crumpton knew Mazza was unlikely to receive the death penalty for killing her mother and niece, but she still believed he deserved to spend his life in prison. Instead, she knows he now is likely to walk free one day.

The plea comes after Mazza’s case meandered through six judges and six previous defense attorneys. A witness died.

No defendant should ever spend 10 years in jail awaiting trial. But, by the same token, no victim’s family should ever have to watch prosecutors accept a plea deal after the case has languished for so long.

A speedy trial is not about defending the rights of the accused over the victims. It certainly isn’t about placing the victim ahead of the defendant. But it should be about valuing justice and fairness over everything dispassionately.

It’s hard to see anything dispassionate and fair for anyone about a slow-motion train wreck derailing justice.