Forty-four years would have seemed like a lifetime to a 24-year-old man in 1975.

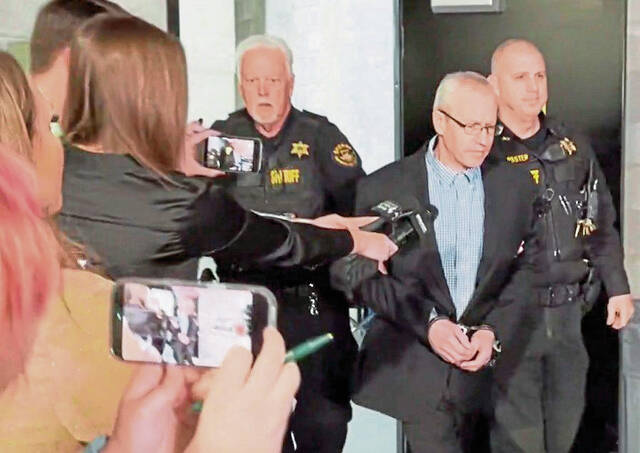

Robert Wideman, now 68, was just 24 when charged with second-degree murder. He was convicted the next year and sent to prison for life.

Nicola Morena was 24 back in 1975, too.

Morena was the man who died in the robbery in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Overbrook. Wideman didn’t shoot him, but he was one of the three men who participated in the crime.

Wideman’s sentence was commuted by Gov. Tom Wolf on Tuesday. After 44 years, Wideman will get to come home to his family (after a year in a halfway house).

He comes home over the objections of Morena’s family. He comes home over the objections of Allegheny County District Attorney Stephen Zappala Jr. Both opposed his bid for commutation with the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons, which voted in May to release Wideman.

Morena’s family doesn’t get him back.

The criminal justice system is a complicated machine because none of the parts are just pulleys and gears. They are people and pain, and being fair to one person can feel like being cruel to someone else.

At the board’s hearing, there was just one witness. Allegheny County Judge Jeffrey Manning pushed to end Wideman’s sentence. He knows exactly how long has passed since Morena’s death, because in 1976, he was the assistant district attorney who prosecuted him.

Under Pennsylvania law, second-degree murder is the charge you receive for a death that occurs in the commission of another crime. You might not have pulled the trigger. You might not have intended for anyone to die. But you did knowingly commit a crime, and this is how you are held to account.

Manning opposes that law.

A victim’s family would no doubt disagree.

That painful, imperfect criminal justice system is being reformed at different levels, but as it moves from past problems to new processes, it’s important to remember that it will always be imperfect and it will always be painful.

We can try to mitigate places where it has been unfair, and we can try to improve it — to make people safer, to give victims and their families a voice, to protect rights and to prevent the system itself from turning a one-time mistake into a criminal career.

Still, at the end of the day, when you are dealing with a murder, there will always be someone who doesn’t get to come home.

And for that family, no amount of remorse or rehabilitation may ever restore what they lost. That is understandable.

But 44 years might be justice, even if it’s not perfect.