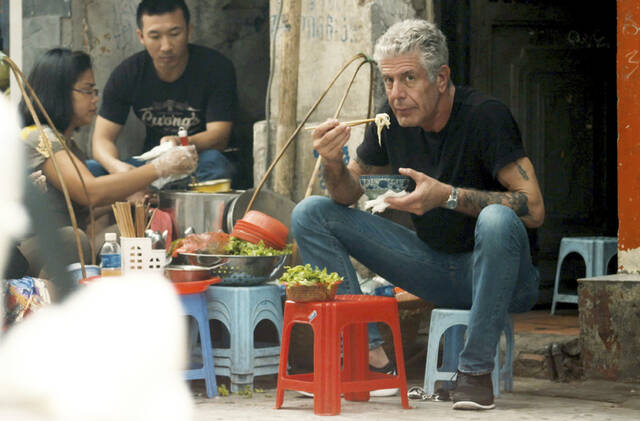

With CNN airing its new “Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain” this month, the public’s fascination with the late chef, writer and travel storyteller, who died in 2018, continues. Part of the interest may be due to Bourdain committing suicide and the difficulty for many to understand why someone at the top of his game, and beloved by many, would choose to take his own life. His suicide again reminds us that success, wealth and fame don’t make one immune to the effects of depression.

Like Bourdain, I am part of a generation where men did not admit to being depressed, nor did they cry, because it was viewed as not being a “real man.” You were taught to be thankful for what you had. After all, your parents had lived through the Great Depression and World War II and were thankful just to have survived. You were told that your feelings would pass, or to “just to get over it.” Only those viewed as having serious psychological problems sought counseling. People often self-medicated with alcohol or drugs, or engaged in risky activities so adrenaline and fear would replace feelings of depression.

Bourdain was at one time a heroin addict. Did he use drugs as a way to combat the sadness and helplessness that depression causes? Could he have avoided his addictions if he had sought help for depression earlier?

Family and friends are often shocked by suicide, saying there were no outward signs of problems. Bourdain’s mother said he was “absolutely the last person in the world I would have ever dreamed would do something like this.” The reality was that Bourdain, like many men, was good at masking signs of depression. They are great actors who follow a script established by generations of men that before them.

When I was growing up in small-town Western Pennsylvania, suicide was a taboo topic. Our local newspaper never mentioned suicide in an obituary. Drug overdoses were explained away as an adverse reaction to medication; for people who shot themselves, the story was that the gun accidentally discharged. For many families, it was a scarlet letter of shame, a failure.

The fact that depression could have contributed to someone taking his or her life was never discussed; depression was thought of as a character flaw, not clinical in nature. Even mention of going to a counselor or obtaining a prescription could result in puzzled looks or ridicule. And who could afford such treatment, and where would you even go?

We have come a long way in better understanding and treating depression. It is no longer viewed as a scarlet letter or sign of weakness to admit to depression. Actors, athletes, politicians and other high-profile figures have announced their treatment for depression. We also can better recognize the warning signs of someone related to people considering suicide.

Despite this progress, many men still avoid getting help.

A man acknowledging that he may be depressed is not a declaration that he is less of a man. To me, it means he is more of a man because he is facing the problem and hopefully dealing with it. Counseling and medication help. Let’s let men know that there is no shame in seeking assistance.

Greg Fulton is a Western Pennsylvania native living in Denver.