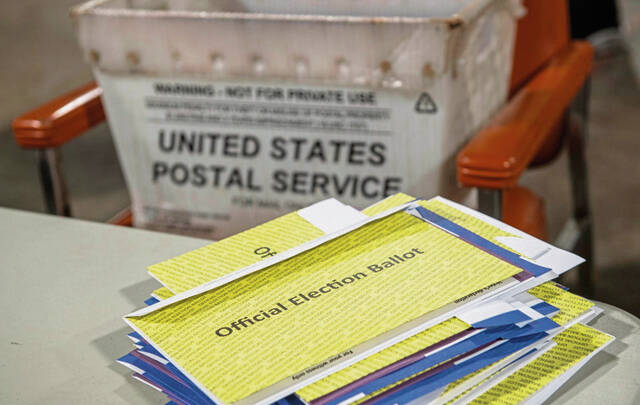

Pennsylvania voters who commit paperwork errors with their mail ballots could risk their votes being rejected in the days ahead — depending on which county they reside. Thanks to failed leadership from commonwealth Secretary Al Schmidt and the General Assembly, a voting rights “Wild West” has flourished where counties are left to craft procedures — often unwritten — about if and how voters who face ballot rejections can fix their errors. Now, the U.S. Supreme Court has been pulled into the legal tangle that has been building across numerous lawsuits since 2020.

Failing to follow instructions on dating and signing return envelopes could lead to substantial numbers of rejected ballots for “disqualifying errors” across the commonwealth this year. Some might forget to return the necessary ballot secrecy covers as well. Signing or dating wrong (or failing altogether) are quick ways to earn a rejection. However, some counties give voters opportunities to cure the deficiencies — but the means by which errors are corrected and how voters are alerted to the need to cure will vary.

In August, attorneys and researchers for the Public Interest Legal Foundation traveled across the commonwealth to survey practices and policies about ballot curing. We anticipated some pro-and anti-curing practices across the state. But the real surprises came between the counties with curing. Whereas some counties would allow curing but make no affirmative effort to inform the affected voter, other counties dedicated themselves to exhausting every known means of contact. Next came the differences in curing process. Some counties who would not be calling any voters plan to allow curing only in the county elections office. Allegheny County, by contrast, planned to mail the defective paperwork back to voters to make corrections from the comfort of home.

Let’s recap: Curing is acceptable in some counties and prohibited in others. Even where it is acceptable, the process can be more difficult or taxing to complete depending on where you live in Pennsylvania. You don’t need a law degree to sense a basic unfairness in that environment. Anyone with a law degree could tell you this all sounds like an equal protection violation worthy of the Supreme Court’s notice.

This week, the foundation filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court of the United States in Genser v. Butler County Board of Elections. Largely at issue is whether provisional ballots are an acceptable safety net for voters whose ballots were rejected in some counties. And while the key parties are acting out of partisan interests about whether curing should be allowed this November, we instead hope the court will take notice to equal protection guarantees within the Pennsylvania Constitution. The foundation does not take a stance here on curing — only that the policy, whatever it is, be clearly defined and fair to all. That is not happening. In fact, several counties told the foundation that its curing policy did not exist in written form and could change on a voter-by-voter basis. We even found legal disagreements about using provisional ballots among the curing-friendly counties.

We focus on equal protection matters in the case because that sets Pennsylvania on the path to ultimate resolution of the problem. Courts do not like to make election law right before Election Day — it’s bad for morale and violates established legal precedent. Worse, the Pennsylvania executive and legislative branches have put the courts into tough spots on this topic for years. Instead of having a confusing law that partisan interests need interpreted in time for voting, Pennsylvania’s legal architecture around mail voting is silent on rights to cure. Curing is neither legal nor illegal — it simply depends on whether your county leadership wants to engage in the practice.

No matter who the Supreme Court finds for, the dispute is only resolved for this November. Not the next one. This is ultimately thanks to a failure in leadership with Schmidt. For years, his office knew about this gap in the law and it is still not filled. Legislators give considerable reliance to the insights of state and county election officials when crafting new law. Schmidt has failed in leveraging his position to address the problem. Pennsylvania’s peer states are not having to litigate this question in late October.

No one wants national attention over rejected ballots in Pennsylvania this November. The U.S. Supreme Court is ideally placed to weigh these matters with an eye toward equal protection for all. The status quo is unacceptable and practically unique compared to other states. If policymakers and authorities do not act, we will repeat this fight in 2026 and beyond.

Logan Churchwell is the research director for the Public Interest Legal Foundation, a nonprofit law firm devoted to election integrity.