Pennsylvanians just voted in primary elections to nominate Democratic and Republican candidates for the office of state auditor general. Those candidates will face off against each other in November.

I teach courses about American politics and elections at Penn State. Every time I ask students if they know what the duties of the auditor general are, none of them know. If I ask them the name of the current Pennsylvania auditor general, none of them know. And when I ask if they can name any of the candidates for auditor general, even if they plan to vote within a week, none of them know.

While my students are newer to the political system than most voters, I doubt that most Pennsylvania residents have any idea who their state auditor general is, or what that office does.

So when given a ballot, how are voters supposed to decide who is the best candidate for the office that examines whether state tax money is being spent properly and whether state government programs are working effectively, and as intended?

In a general election, voters may have seen some advertising, and most likely vote with partisan preferences. But in primary elections, with less advertising, that doesn’t work. The ballot can be crowded with candidates voters don’t know. When confronted with such a choice, some voters pick a name because it sounds familiar.

Consider the plethora of candidates named Bob Casey in the 1970s. One Bob Casey, the father of current U.S. Sen. Bob Casey, had been the state auditor general and later was the governor of Pennsylvania. Another was a local official from Cambria County; he won the Democratic primary for state treasurer in 1976 and the general election later that year.

Yet another Bob Casey, a teacher and ice cream-seller from Pittsburgh, won the Democratic primary for Pennsylvania lieutenant governor in 1978 — the same election when the “real” Bob Casey lost a primary for governor. It’s easy to understand why voters were so confused.

But if voters can’t choose a candidate on the primary ballot based on a familiar name, how else can they decide? Pennsylvania is one of only a few U.S. states that provides another clue on its primary ballot: the county of residence of the candidate.

For many years, Pennsylvania has had strong regional political rivalries and divisions between the Philadelphia and Pittsburgh areas. On primary election ballots, voters in the Philadelphia area often vote for the candidate who is from Philadelphia, or from nearby Montgomery, Delaware or Bucks counties. Voters in the Pittsburgh area tend to vote for the candidate from Allegheny County or one of the surrounding suburban counties. Most of eastern and western Pennsylvania’s voters follow suit, choosing the candidate from their side of the state.

The tendency of central Pennsylvanians to vote for the Pittsburgh-area candidate has often allowed western Pennsylvanians to win primaries. But that practice gets confounded when candidates from central Pennsylvania are on the ballot, too.

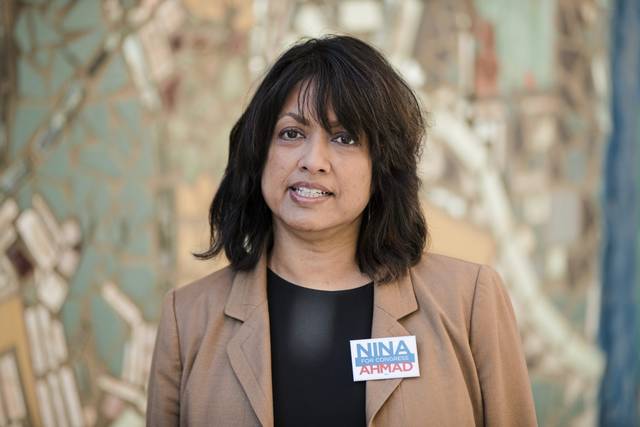

That is exactly what happened with the recent Democratic primary for auditor general. There were six candidates on the Democratic primary ballot this year — Nina Ahmad of Philadelphia, Michael Lamb of Allegheny County (Pittsburgh), Scott Conklin of Centre County (State College), Rose Davis of Monroe County (East Stroudsburg), Tracie Fountain of Dauphin County (Harrisburg) and Christina Hartman of Lancaster County.

Political observers knew that Ahmad and Lamb were the likely front-runners, due to endorsements, campaign fundraising and their political backgrounds in the state’s two largest population centers.

Once all the votes were counted, Ahmad emerged as the statewide winner with 36% of the vote, followed by Lamb with 27% of the vote. Hartman finished with 14% of the state vote, and the other three all received less than 10% statewide.

The sources of those vote totals were revealing. Ahmad won 72% of the vote in the six-way race in Philadelphia and more than 59% of the vote in every county bordering Philadelphia.

Lamb won more than 70% of the vote in Allegheny County and every county that borders it. He finished far ahead of his five opponents in every county in the western quarter of Pennsylvania.

The rest of Pennsylvania largely went for the other four candidates, generally choosing whomever lived closest to their homes.

Hartman won easily in her home county of Lancaster, with 75% of the vote. She finished first in every county bordering hers except for Dauphin County, which is home to Fountain, who won 63% of the vote there. Fountain also won by large margins in the two suburban counties directly west of Harrisburg.

Conklin, of Centre County, only won 7.5% of the state vote but won more than half the vote in 10 central Pennsylvania counties. He finished first in many others. Davis won her home Monroe County with 76% of the vote. She finished first in three other neighboring counties.

This is not the first time this has happened. The same pattern occurs in most Republican and Democratic statewide primaries for offices and candidates that voters know little about, including statewide judicial elections and elections for statewide offices like auditor general, state treasurer and lieutenant governor.

What’s the solution? Given how little information voters have about any of the candidates or offices in primary elections, it doesn’t seem productive simply to eliminate county of residence from the ballot and leave voters with even less information than they have now.

One idea would be for party leaders to choose candidates, since those leaders probably know more about who is most qualified and who would be a stronger general election candidate. Another idea is not to vote for so many offices. In Erie County, where I live, we elect 79 different offices, including a county coroner. It doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense to elect dozens of people we know nothing about to offices we know nothing about.

However, Americans are stuck on the idea that electing everything is part of our democratic heritage. Given that, Pennsylvania’s transition to mail-in balloting this year provides an opportunity. When candidates qualify to be on the state ballot in Pennsylvania, perhaps they should now be offered visibility on a state election website. On that website, all the candidates for all the offices can list some biographical information and state their positions on a standard set of issues compiled by non-partisan voter groups.

Some privately run websites and voter groups do that now, but not all voters are aware of those efforts, and it is hard to get information about all offices and candidates at once across all parts of the state. As more Pennsylvanians vote by mail at home, perhaps some can be encouraged to visit a central website to learn more about candidates than simply their name and county of residence before deciding how to vote.

Robert Speel is an associate professor of political science at Penn State Behrend, Erie.