Most states have already finalized their new congressional maps, with candidates jockeying to gain their party’s nomination, and hopefully win a seat in the 118th Congress during the upcoming November midterm election.

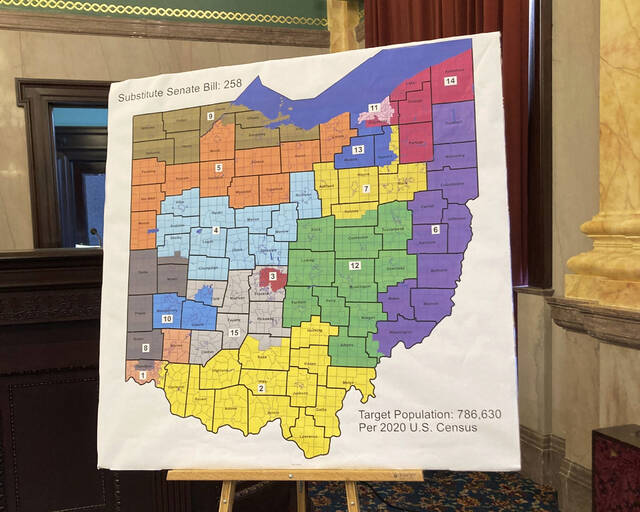

Ohio is bucking this trend, with the first Republican supported map invalidated by the state’s Supreme Court back in January. A revised map, which also gave Republicans an overwhelming edge in the upcoming midterm election, could not gain support from the court in March.

With May 3 set for Ohio’s primaries, the likelihood that the mapping debacle will get resolved to everyone’s satisfaction by then is remote, forcing a federal order for an unconstitutional map to be used in 2022 and 2024, with a new map set for 2025-26.

Partisan gerrymandering is not new, and certainly not unique to Ohio. The eye test for Illinois’ new congressional map reveals an egregious gerrymander by a Democrat-controlled legislature. The Princeton Gerrymandering Project graded the map as F for fairness, competitiveness, and geography (with F standing for “Fail”, not “Fair”). Florida’s mapping fiasco instigated by their Republican governor has drawn national attention, also earning an overall grade of F.

By comparison, Pennsylvania’s mapping conflicts were relatively placid, earning an overall grade of B for the adopted map drawn by academics.

Both parties are guilty of exploiting the redistricting process for their own gain. The party holding the mapping power is typically the gerrymandering perpetrator.

The mix of political leanings amongst the people who appoint the members of the Ohio Redistricting Commission ensure partisanship of the commission, guaranteeing a pathway for gerrymandered maps to be drawn and enacted into law.

Gerrymandering weakens democracy. It permits legislative bodies or partisan commissions to pick voters for candidates, rather than allowing voters to elect their representatives.

In a technology-centric world, we can do better, and we should do better. And the way to do better is to use computational algorithms to design and score congressional maps.

Computational algorithms are available to draw maps with any desired objectives. For those interested in fair maps, measures like efficiency gaps (which measure and compare wasted votes by each party) or compactness (how geographically tightly drawn districts are) can expose egregious gerrymandering. These same measures can be also used to draw highly partisan maps.

Partisanship can be injected into computational algorithms. But the partisanship cannot be hidden when reviewing the end results. No matter how maps are drawn, the tools of computational redistricting are available to shine a bright light on nefarious intent ensconced in the final proposed maps.

Anytime maps are drawn that require review by the courts, the mapping process has failed. Even when gerrymandered maps are enacted into law, ongoing legal challenges and court battles ensure that public resources are being wasted to defend or overthrow maps that should never have been proposed.

The Ohio mapping debacle demonstrates why map drawing and evaluation require computational algorithms as the vehicle to protect the interests of voters. Unfortunately, the very people, elected officials, who have the power to change the mapping process also have a vested interest to maintain the status quo. This obvious conflict of interest means that structural changes to mapping processes will likely require federal legislation, though that too is unlikely to yield productive and constructive changes anytime soon.

Technology is the mainstay of our lives. We trust it for communication, transportation, and commerce. Yet some remain suspicious when it comes to drawing maps. Indeed, the only people who voice their suspicions are those who hold the mapping power and have the most to lose.

Voters deserve to be treated better. Computational redistricting is how they can be treated better.

Sheldon Jacobson is a professor of computer science at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and founding director of the Institute for Computational Redistricting, with a mission to provide transparent approaches for redistricting grounded in computational methods.