More than anything, John Wehner remembers a sound in the locker room.

The Pittsburgh-born Pirates infielder was part of the team that lost Game 7 of the 1992 National League Championship Series, 3-2.

“It’s dead silent except for the clubhouse guys. Out of breath. Heavy breathing,” Wehner said.

The clubhouse attendants were winded from feverishly tearing down the staged celebration in the Pirates locker room after their ninth-inning blown lead.

And moving everything into the Atlanta Braves locker room instead.

“All the plastic. The trophy. The booze. Everything had to be taken out of our clubhouse and put into their clubhouse. Right there. Right then,” Wehner said. “It was as quiet as I ever heard in the clubhouse. The bus to the airport. The plane home. I don’t think I heard a sentence, a syllable.”

For as devastating as the loss was as a singular game, the defeat was much more for that group of Pirates — and for fans in Pittsburgh. The instant that ex-Pirate Sid Bream was called safe at home plate after Francisco Cabrera’s game-winning base hit, everyone knew the good times for the franchise were finished.

Not just for the following year but for many to come. As it turns out, for the better part of three decades.

Bream’s slide not only ended the Pirates’ 1992 season, but it also began a slide for the franchise that is still happening today.

‘We knew that was our last shot’

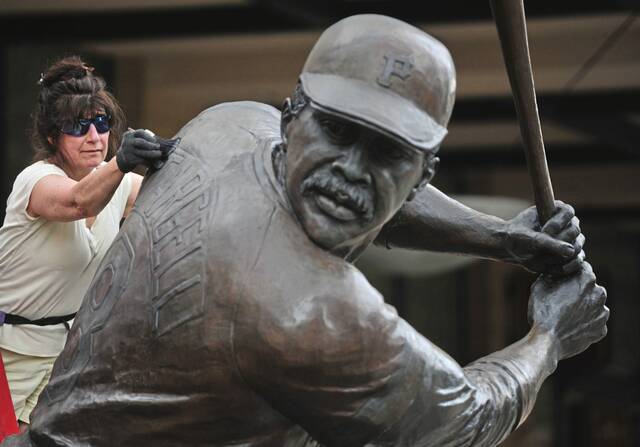

The old adage is that “a picture tells a thousand words.” In the case of former Pirates All-Star outfielder Andy Van Slyke, one picture of him tells the tale of 2,586 losses.

That’s the number of regular-season defeats the Pirates have endured since that brutal night in Atlanta on Oct. 14, 1992. Not counting the strike year of 1994 or the coronavirus-shortened season of 2020, that’s 92.4 losses per season.

Strange. Somehow it feels like that number should be more, doesn’t it?

Many Pittsburghers vividly recall that painfully iconic television shot of Van Slyke sitting in center field, ashen-faced after the team had just surrendered a 2-0 lead in the ninth inning of a game that would’ve sent the franchise to its first World Series since 1979. The slumped shoulders and expression on Van Slyke’s face was a perfect encapsulation of what the entire team — and the entire fan base — was feeling: simultaneously dumbstruck as to what just happened while also being completely cognizant of what the loss would mean.

“He was sitting on the outfield grass, in disbelief, realizing that this was the end of that Pirates group as we knew it,” CBS play-by-play announcer Sean McDonough recalled. “That cast of players and that manager wasn’t going to go forward together, which made it that much tougher. There was a sense that this was the last chance for that really talented group.”

It was over. Not just the game. Not just the season. But an era of competitive baseball.

“We knew that was our last shot,” Van Slyke said. “It was the best time of my life. … It was just a lot of fun. Very disappointing. It was the best time and the worst time.”

After three straight seasons as National League East champions — and three straight gut-wrenching defeats in the NLCS — the roster was about to dissolve. Everyone knew it. In fact, the looming deconstruction of the team is part of what had made the 1992 playoff run so special.

“We knew it was a possibility,” Game 7 starter Doug Drabek said last month. “Once it was done, it hit a lot of guys to where, ‘What’s next? What’s going to happen for next year?’ It was a combination of that and it was the third year in a row (being in the NLCS), and it didn’t happen. So the combination of the disappointment and the uncertainty of the future popped into a lot of guys’ heads.”

Coincidentally, Bream’s free-agent departure for Atlanta after the 1990 season was one of the first dominos to fall. All-Star outfielder Bobby Bonilla signed with the New York Mets for $29 million over five years after the ’91 NLCS loss. In March, general manager Ted Simmons traded 20-game winner John Smiley after the lefty agreed to a $3.44 million contract following an initial arbitration filing.

“I would have been willing to stay here for a fair price,” Smiley said at the time. “I’m not a big money person. … If they would have made me a reasonable long-term offer, I would have gladly stayed. They didn’t even make me an offer, though.”

Now that the ’92 season had drawn to a close, Drabek and two-time MVP Barry Bonds were destined for free agency, with little to no hope that the Pirates would retain their services.

The fans, the local media, everyone saw labor struggles on the horizon, skyrocketing player contracts and disproportionate television revenue. Not to mention that the team was still being operated by the nebulous “Pittsburgh Associates” consortium, with no clear-cut owner in sight.

At that moment, with Van Slyke and Bonds still rendered motionless in the outfield as the Braves celebrated at home plate, if you had gone forward in time and returned to say, “Hey, I just came back from the future, and the Pirates are not going to have another winning season for the next 20 years,” a lot of people in Pittsburgh would have believed you.

Sometimes being right isn’t fun.

‘I knew it was time to move on’

Bonds went to San Francisco for a then-record $43.75 million, six-year contract. Drabek went to the Houston Astros for $20 million over five years. The Pirates offered $19.5 million. But Drabek’s home was there. And the threat of cost reduction on the roster made staying in Pittsburgh far less appealing.

Pitcher Bob Walk, who spun a gutty complete game in Game 5 to extend the series, stayed one more year, posted a 5.86 ERA and then retired.

“We knew that was just going to continue,” Walk said. “I’m in my late 30s. So I know that even if they rebuild this — looking back over the years, they didn’t rebuild anything — but even if they rebuild this, it’ll take a couple of years. I’m not going to be around here anymore.”

That 1993 team fell from 96 wins and an NL divisional crown to just a 75-87 record and a fifth-place finish. It would be the first of 20 consecutive sub-.500 seasons.

It wasn’t long before the rest of the roster withered away. Catcher Mike LaValliere was released in 1993. Tim Wakefield, who would’ve been named 1992 NLCS MVP had the Pirates held on to win Game 7, lost the touch on his knuckleball. He was demoted and eventually released. The season-shortening strike hit in 1994. Once it was over, Van Slyke signed in Baltimore.

In 1995, there was plenty of talk about the franchise moving to Northern Virginia or Orlando, Fla., until newspaper heir Kevin McClatchy bought it in 1996 for $95 million.

Manager Jim Leyland stuck around through that ’96 season, an 89-loss campaign that saw the Pirates finish last in the National League Central for the second time in the division’s three-year existence. Leyland resigned after the season.

“I never wanted to leave Pittsburgh,” Leyland said. “I didn’t want to go somewhere else to manage. Originally, they thought they might sign some mid-range free agents. That would’ve been OK. I knew we couldn’t sign the big boys. But Kevin decided they had to strip it down and rebuild it again. And I knew it was time to move on.”

The next year, Leyland led the Florida Marlins to the 1997 World Series crown.

Meanwhile, the Pirates had “The Freak Show” team under Leyland’s successor, his former bench coach, Gene Lamont. Despite its humiliating $9 million payroll, the group of castoffs, prospects and never-was players managed to stay in the 1997 race for a weak NL Central crown into September but still finished below .500 with a 79-83 record — an embarrassing high-water mark for the organization for the next 15 years.

‘That’s ridiculous to me’

In 1998, funding was approved for a new stadium through the controversial “Plan B” proposal. Had that not occurred, the Pirates may not be here today. After construction was complete on the sparkling new facility, it proved to be the lone, meaningfully good thing the franchise accomplished since Wakefield won Game 6 in ’92.

But it never translated to winning. And it rarely translated into spending enough to fielding a competitive roster. When familiar names were acquired — see: Bell, Derek and Burnitz, Jeromy — they were busts. When pennies were pinched, the likes of Jason Schmidt and Aramis Ramirez became multiple-time All-Stars with other teams.

The first 12 seasons of the new park never yielded plus-.500 baseball. The same promises continued. Assurances that young stars were in the pipeline. Unfortunately, they either never developed or were moved to other teams once they got too good — and too expensive — to keep.

In 2007, McClatchy ceded control of the team to current owner Bob Nutting. By 2013, the Pirates put a temporary stop to the hex that had haunted the franchise. Behind the on-field leadership of manager Clint Hurdle and MVP Andrew McCutchen, the Pirates made the playoffs as a wild card three years in a row, and PNC Park felt like how Three Rivers Stadium used to feel in the ’90s.

Until the cycle repeated itself. Only once (in 2013) did that group of Pirates advance to the divisional series round, and like the ’90s teams, they never won a series.

Also mirroring the ’90s teams, after the third year of trying, general manager Neal Huntington — who helped build the roster in the first place — tore it down. Piece by piece, Huntington sold off components such as Gerrit Cole for inadequate or nonexistent return. Despite a fleeting season barely above .500 (82-79) in 2018, he and Hurdle were dismissed after the 2019 season.

Now current general manager Ben Cherington and manager Derek Shelton have presided over consecutive 100-loss seasons.

Even Bream, the Freddy Krueger of Pirates fans’ nightmares, wants better for the franchise he loged and once called his own.

“Thirty years to the day on Oct. 14, and they haven’t been over .500 in 26 of those years. That’s so ridiculous to me,” Bream said. “You can say small market. But the Minnesota Twins, Oakland A’s, Cleveland (Guardians), they all do it. The Pittsburgh Pirates can be doing it too.”

‘A Pirates fan is the best fan in sports’

Sometimes we see it in sports. A much-maligned franchise finally wins a title. Those who came close and failed in the uniform before get their public reprieve from the fan base.

Like when a teary-eyed Bill Buckner came back to throw out the first pitch at Fenway Park in Boston after the Red Sox had won the World Series in 2004 and 2007.

It’s a cathartic “You’re off the hook now. Thanks for getting us as close as you did.”

I asked Van Slyke if that’s something he’d like for himself and all of his former Pirates teammates. Of course, that’s if the Pirates could ever win a World Series in his lifetime.

“I would just like to get back to the days where the front office makes an effort to get back to the playoffs,” Van Slyke said. “If you start with an effort, maybe your chances increase. But when you are so disingenuous for 30 years, it’s too obvious. In a lot of ways, a Pirates fan is the best fan in all of sports. I mean, they are selling you the Brooklyn Bridge every year.”

Pittsburgh has plenty of bridges. They all need to be repaired. But we don’t need another bridge.

What we need is a baseball team good enough to get a crack at another ninth inning, with a lead, with the World Series on the line.

And it’d be nice if that happens before another 30 years vanish.

Listen: Tim Benz and Jim Leyland remember Game 7 of the 1992 NLCS