When assessing a Pittsburgh Pirates offense that ranked last in the major leagues in home runs, runs scored, RBIs, slugging percentage and OPS, general manager Ben Cherington didn’t mince words.

“We’ve got to score more runs,” Cherington said.

How the Pirates will do that will be the focus of their offseason and the key to whether they can go from a 91-loss team to making a push for their first postseason appearance in a decade.

“Some of that needs to come internally, no doubt. Whether it’s guys that have produced at a high level in the past and getting them back to that level, or improvement from young players, it has to happen. We believe it can happen,” Cherington said. “And yes, of course, we need to try to strengthen the offense through acquisitions this offseason, too.”

The internal improvement is most important, especially after the Pirates got substandard seasons from their top offensive players.

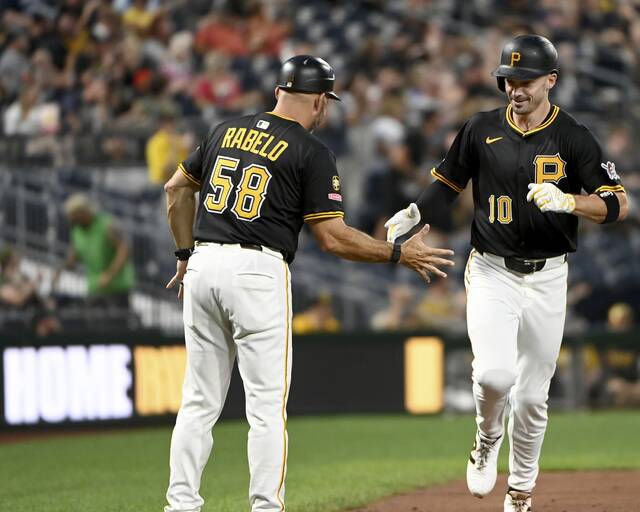

• Bryan Reynolds, their highest-paid position player at $12.25 million, had a career-best 38 doubles and led the team in RBIs (73), despite a drop from 88 in 2024. But his 16 home runs were his fewest since his rookie season in 2019, and he also had a career-high 173 strikeouts and a career-worst 26.5% strikeout rate.

• Oneil Cruz produced a 20-20 season with 20 home runs and 38 steals — which tied for the National League lead — but endured a second-half swoon in which he batted .200/.298/.378. Cruz struck out at a 32% rate and led the team in strikeouts (174).

• Andrew McCutchen led the team in walks (67) and on-base percentage (.333), but his 13 home runs and 57 RBIs ranked second-worst among all qualified designated hitters and his .367 slugging percentage and .700 OPS were the lowest of any DH.

Despite shining on the Home Run Derby stage, that Cruz didn’t develop into an All-Star proved troubling. He bated .177/.255/.311 in 50 games in the second half, when the Pirates often sat him against left-handed pitchers because of his .102 average and .400 OPS.

Cruz led the majors in bat speed and average exit velocity and ranked among the best in barrel and hard-hit percentage, as well as walk rate (11.8%), yet batted 29 points below his expected average and slugged 59 points lower than expected. His 32% strikeout rate and 34% whiff rate were among baseball’s worst.

“It’s definitely something that we’re really, really digging into and focused on. It’s really important,” Cherington said. “We thought he was there for a couple of months. He got off to a little bit of a rough start, stabilized and then was proving he could play center field. That part, I think he mostly has done. It looked like for a couple of months that he was about to reach that next level, but it hasn’t happened.

“I think particularly since the All-Star break, the offensive production just hasn’t been there. He’s aware of that. We’re digging into it with him. I think the offseason is going to be really important for him. Mostly, it just comes down to approach and swing decisions with him. When he makes contact and barrels the ball, still really good things are happening. It’s just what pitches he’s swinging at and how consistent in that approach. It just hasn’t been there for him in the second half of the season.”

What bothered Pirates players the most is their actual statistics didn’t align with their expected averages, which were considerably higher. Reynolds produced the best exit velocity and second-highest hard-hit rate of his career yet saw his power numbers drop. McCutchen’s expected batting average was 28 points higher, and his slugging percentage was 62 points higher than his actual numbers.

“I try not to get too big into the metrics and the numbers but obviously, as a whole, it’s not just one or two people but the entire team, offensively at home we just haven’t slugged — and that’s a problem,” McCutchen said in August. “I don’t think it’s strictly on the offense. I don’t think it’s just us. Obviously, the expected doesn’t give the full picture on what you’re doing or what you’ve done. But when you’ve got a lot of guys whose expected numbers are 100 points or 100-plus points higher than what they should be, there’s something there. I just think that needs to be answered. We need to figure out the whys.”

McCutchen believes a deeper dive into the analytics of the difference between the Pirates’ expected and actual statistics could help explain why the offense hasn’t produced. Because Pirates players are at a loss.

“I don’t think we as an offense or as a team pressed on it,” McCutchen said. “When it comes to the numbers, you can look at stuff and make people look really bad. Or you can look at numbers, and you can make that same person look really good. That’s how much is out there from an offensive standpoint.

“You can look at the standard OPS as a team, slugging as a team, runners in scoring position, whatever. You can look at that and be like, ‘These guys are really bad.’ Or you can look at expected, a lot of other things that go into the offense and say, ‘This team really isn’t that bad.’ There’s just something that’s happening that’s causing their numbers to not be as good as they were even a year prior. I’ll tell you, it’s one thing when it’s one or two or three or four guys doing it. But when the whole team’s doing it, there’s something going on. Not necessarily in a sense of a conspiracy theorist. We just have to dive in a little deeper.”

Some Pirates hitters blame the ballpark, with a widespread belief the ball doesn’t carry at PNC Park and it takes a Herculean dead-pull effort to take advantage of the 325-foot fence down the left-field line. Its dimensions can be daunting for right-handed hitters, especially the 410-foot North Side Notch in left-center. McCutchen and Reynolds have asked the Pirates to move in the left-field fence, much like the Baltimore Orioles and Toronto Blue Jays have done in recent years.

“I’ve asked for that left-center wall to be moved in for so many years. For some reason, they won’t do it,” said McCutchen, who hit only four of his 13 homers at PNC Park. “There’s no point having it there. There really isn’t. It’s not like the ball rolls there. The grass catches it by the time it gets there, anyway. What’s the point of it being there? It’s not like we’re hitting so many more triples because that left-center Notch is there. It’s still not happening. I have mentioned that: What’s the point of it?”

The point is that it’s made PNC Park a pitcher-friendly field, especially for left-handers, because of its cavernous dimensions in left-center and center and the 21-foot Clemente Wall in right field.

But the Pirates’ starting rotation, led by NL Cy Young favorite Paul Skenes, is composed primarily of hard-throwing righties. Reynolds is a switch hitter who hit four of his 16 homers to left field, and Cruz is a lefty who hit five of his 20 homers to either left or left-center.

As someone who has played left and center field and attempted to hit home runs to the deepest part of the park, Reynolds is no fan of the North Side Notch and would prefer to see it straightened.

“People love talking about it, so it’s probably not going to happen,” Reynolds said. “It’s cost us a bunch of runs. You shouldn’t have to hit a ball 420 feet to left field to hit a home run. … I’m not saying make it 200 feet, but 400 feet is absurd. We already have it where the ball doesn’t fly.”

Reynolds has as much of an issue with the green batter’s eye, which reflects the sun for much of the season.

“It’s 410 feet to left field, and you can’t see off the batter’s eye for the first three at-bats for half the year,” Reynolds said. “I’ve been telling them to make it matte black for six years, and we haven’t. Every batter’s eye you go to is black, so it eats the sun up. It’s just plastered in your face. When the sun’s blasting on that, you can’t see for two at-bats, at least.”

Pirates players, both past and present, are quick to point out that other teams have adjusted their ballparks to better serve their players.

At Camden Yards, the Orioles moved in their left-field wall — nicknamed Walltimore — anywhere between nine and 20 feet in spots and lowered the fence 3 to 6 feet, and found that 29 balls that would have been non-homers in 2024 went out this season. The Detroit Tigers moved in their left-center fence at Comerica Park from 422 to 412 feet and lowered the fence from 8 1⁄2 feet to 7 feet high.

“If we can make an adjustment as a ballclub to help the offense out a little more,” McCutchen said. “I don’t know what that means. Does that mean moving the fences in a little bit? Does it mean cutting the grass a little bit shorter, like they did in Kansas City? Because those boys were struggling, so they said, ‘You know what? We’ll just rip out all the grass and give you new grass.’ For people that say stuff can’t get done, it can get done.

“I think there needs to be a lot of stuff that goes into the reasons of why, not just looking at home or road split or you score runs at home but you don’t on the road. But for some reason you don’t slug at home, but you slug on the road. There’s a bunch of stuff that needs addressed, I think.”