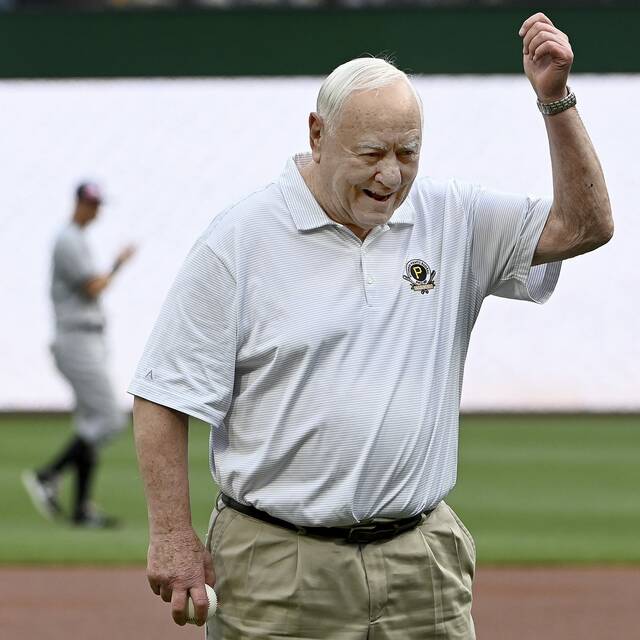

With the anniversary of Game 7 of the 1992 National League Championship Series fast approaching, I reached out to former Pirates manager Jim Leyland. Not long after I sent a text message requesting a telephone interview, he called back.

“Hi, Jim. Thanks for calling. I appreciate it.”

“What are you trying to do,” Leyland replied. “Break my heart again after 30 years?”

Three other managerial stops. Three trips to the World Series. Three decades.

All of those things happened in Leyland’s life between Oct. 14, 1992 and our conversation last month. But the disappointment of that night still resonates with him.

“We had a good team. We played great baseball. We even played good baseball in the playoffs,” Leyland said of that series against the Atlanta Braves. “We just lost a really gut-wrenching Game 7. … Certainly felt great going into that ninth inning. It was just a great ballgame. Then a couple of freaky things happened.”

Yup. About a half-dozen “freaky things.” All of which culminated in Francisco Cabrera’s base hit, which scored former Pirate Sid Bream to win the game for the Braves, 3-2. They went on to the World Series. The Pirates went on to 20 consecutive seasons of losing baseball.

A role player off the bench with 10 Major League at-bats that season, driving home a 32-year-old man with five knee surgeries under his belt to beat the throw of a Gold Glove, MVP outfielder for the winning run.

As if that wouldn’t have been “freaky” enough.

Outside of Pittsburgh and maybe Atlanta, that play is basically all that is remembered from that night. I often wonder whether Braves fans even bother to recall much of the ninth-inning rally that led to that moment. I’m sure they don’t. At least not to the degree Pirates fans are forced to dwell on it.

How could they? They’ve had 18 years of playoff moments to remember since then. Don’t they run together after a while?

Meanwhile, the Pirates have had a total of three wild-card games and one divisional playoff series since.

The image of Bream beating Barry Bonds’ throw and Mike LaValliere’s tag will always be remembered. But the wounds of the rally that led to that slide also have left scars in Pittsburgh.

‘I’ve thought about it a thousand times’

The hero of Game 5 couldn’t stand to watch the ninth inning of Game 7.

Pirates pitcher Bob Walk was roaming the bowels of Atlanta Fulton County Stadium. His arm was “absolutely on fire” after tossing 128 pitches en route to a complete game three nights earlier. That 7-1 win kept the Pirates alive in the NLCS. Tim Wakefield’s 13-4 complete game victory in Game 6 on Oct. 13 forced Game 7 the next night.

That final contest was much closer. The Pirates held a tenuous 2-0 lead heading into the ninth inning with former Cy Young winner Doug Drabek on the mound.

“When the inning started, I was really confident, but I didn’t want to watch it,” Walk said. So he camped out underneath the dugout in an open dirt area near a batting cage en route to the visitors’ clubhouse.

“Every now and then, you’d hear a roar of the crowd. Then I’d hear another roar of the crowd,” Walk said. “Finally, I couldn’t handle it anymore. I walked out, and I looked to where the dugout was. At that point, I saw Leyland turn around to (pitching coach) Ray Miller and say, ‘Get Walk up.’ Ray saw me. I said, ‘I heard him.’ I grabbed my glove, which was sitting on the shelf, and went out to the bullpen. … That’s where I saw everything unfold.”

For the Braves, it was unfolding. For the Pirates, it was unraveling.

What Walk was hearing underneath the stadium was a leadoff double by Atlanta’s Terry Pendleton, an error by second baseman Jose Lind and a four-pitch walk to Bream to load the bases with nobody out. Already, it felt as if the baseball gods were conspiring against the Pirates.

Pendleton was 0 for 3 on the night and 6 of 29 for the series. The lefty handed-hitting third baseman turned on a 1-1 pitch and pulled it down the line toward the deep right field corner.

Right fielder Cecil Espy either didn’t get a good jump, didn’t hustle, took a bad route, played it conservatively or froze. Whatever the case, he didn’t catch it. Pendleton ended up on second base with a double.

From the archive: More on Bream's slide:

• 4.7.2020: The day Pirates catcher Mike LaValliere finally cussed out the 1992 Game 7 umpire• 12.9.2017: Tim Benz: Sid Bream pulls a Michael Keaton at PiratesFest

• 5.25.2012: Braves to honor Bream's moment

• 10.14.2007: Bummer of '92: Bream's slide lives in infamy

That was the first ball Espy had seen since pregame warmups.

A bench player, Espy pinch-ran for Lloyd McClendon during the previous inning. McClendon, who would manage the Pirates in the early 2000s, was a scalding 8 for 11 in the series. He walked with two outs in the top of the ninth. With shortstop Jay Bell batting, McClendon went to second on a wild pitch. Along the way, though, McClendon said he pulled his hamstring. Espy replaced him on the bases. Bell grounded out, and Espy had to go out to right field cold in the bottom half of the inning.

“I don’t know if it was dehydration or what,” McClendon said. “I’ve thought about it a thousand times. What would have happened if I had stayed in the game? Would my read or jump have been better? You never know.”

The next Atlanta batter in the ninth was clean-up hitter David Justice. He hit a ground ball to the backhand of Lind, the Pirates’ smooth-fielding second baseman. Lind, however, flubbed the play and was charged with an error. He had made only six errors during the regular season. Less than a month later, he would win his first — and only — Gold Glove.

McClendon had an odd premonition about that moment involving first base coach Tommy Sandt.

“In our pregame workouts, Chico took his ground balls like he usually did. Tommy hit him one. He bobbled it. Almost the same play,” McClendon recalled. “Tommy said, ‘One more.’ And (Lind) said, ‘No. I’m good.’ It’s just … you think about that.”

From there, Drabek walked Bream on four pitches, prompting Leyland to replace him with Stan Belinda.

It also prompted 30 years of second-guessing whether Leyland should have pinch-hit for Drabek (after 120 pitches through eight innings) in the top of the ninth. Or whether Leyland should have left Drabek in the game to work out of the jam. After all, Drabek already had wiggled out of one bases-loaded, nobody-out jam in the sixth.

“If they let us replay it, we could find out. I left Stan in a bad spot. I’d like to say, ‘Yeah (I could’ve stayed in).’ But you never know what would’ve happened,” Drabek said. “Adrenaline takes over everything. I didn’t feel tired. I wasn’t thinking about anything besides making a pitch to get outs.”

A moment to believe

In a way, what happened next may have made things easier to digest.

The first batter Belinda faced was Ron Gant. An All-Star. A man who would end his career with 321 home runs. Someone who had hit a grand slam earlier in the series. If he hit another one to end the game, oh well. One of their best beat a relief pitcher who had blown six saves already that season. What can you do?

Gant offered at a 1-0 pitch and cranked it into left field.

“Bonds. At the track. At the wall,” CBS play-by-play man Sean McDonough trumpeted, his voice rising with the crowd. “Makes the catch!”

Pendleton would tag up and score as Bonds’ left foot came within a step of the wall. A near grand slam turned into a sacrifice fly to record the first out and cut the Pirates’ lead to 2-1.

“There was a good feeling for a little bit until we saw Barry camping underneath it,” Bream said. “When it went off the bat, there was that thought, ‘We just won the game!’”

At that point, I couldn’t blame Pirates fans if they had finally started to have faith that their team might escape and win an NLCS after two failed attempts in 1990 and ’91. That ball stayed in the park. Bream was on first base. Another slow runner, catcher Damon Berryhill, was coming to the plate.

Even though Belinda was a flyball pitcher, perhaps a double play was on the horizon. A double play would end the game and send the Pirates to their first World Series since 1979.

Enter home plate umpire, Randy Marsh.

The umpire ‘choked’

Further evidence that something cosmic was working against the Pirates was what happened with the umpires. John McSherry — noted for having a fairly pitcher-friendly strike zone — started the game behind home plate. But he felt dizzy and was replaced by first base umpire Randy Marsh. A bad omen, according to McClendon.

“Not a lot of good things happened to us when Randy was behind the plate,” McClendon insisted.

For instance, Marsh — renowned for having a small strike zone — was behind the plate when the Pirates walked eight Braves batters as part of a 13-5 loss in Game 2.

Berryhill fouled off the first pitch before taking a ball off the plate. The third pitch is where the strike zone started to contract. Belinda appeared to have snapped a pitch right at Berryhill’s knees and on the inside corner, but Marsh called it a ball.

The next pitch was inside for ball three, but it wasn’t by much. And the 3-1 pitch, which was definitely a strike, framed by LaValliere over the inner third of the plate, was also called a ball.

Yes, I'm a glutton for punishment. pic.twitter.com/j17NJvWpKI

— Matt Gajtka (GITE-kah) (@MattGajtka) April 6, 2020

Berryhill walked to reload the bases, still with only one out.

“I don’t want to be pointing fingers, but we had Berryhill struck out. We didn’t get the call(s). That would’ve been the second out of the inning,” Leyland said.

Leyland is reluctant to dwell on the Berryhill at-bat, insisting he doesn’t want to advance a “sour grapes” explanation of what happened. Other Pirates are less concerned about appearances.

“The person who choked the most in that game was the umpire behind home plate,” center fielder Andy Van Slyke said. “When the lights are shining, and it means that much, it just hurts that much more when an umpire can’t pull the trigger when he is supposed to.”

During our interview, Van Slyke wondered if Marsh was “caught up in the moment and couldn’t perform.”

LaValliere joined me for a radio interview on 105.9 The X in 2012. LaValliere held a grudge so long that while he was a roving catching instructor on McClendon’s staff — roughly 10 years after the game — he lost his mind before a spring training game when he saw Marsh and blistered him with a verbal assault so graphic he couldn’t share it on the radio.

“I just lost it,” LaValliere said. “I just started screaming. And all these (young players) are looking at me, like, who is this screwball?”

Apparently, the reason for LaValliere’s tirade was lost on Marsh.

“Randy looked at me, and he had no idea what I was doing,” LaValliere laughed. “I’ve never been thrown out of a game. That was the closest I ever came. And I don’t know if that would’ve even counted because the game hadn’t started yet.”

After Berryhill’s dubious walk, the Pirates got a momentary reprieve. Pinch hitter Brian Hunter looped a pitch behind second base that Lind caught for the second out. It felt like Belinda had dodged a bullet because Hunter had homered during Atlanta’s Game 7 NLCS win in Pittsburgh the previous year.

That brought up Cabrera, a backup catcher/first baseman. However, he had three home runs against the Pirates in his career, including one against Belinda in 1991.

“I knew the guy. I knew what he was going to throw. He was going to throw me slider, sinker, fastball,” Cabrera said.

Up 2-0 in the count, Cabrera roped the third pitch foul. During a recent phone call from his home in the Dominican Republic, Cabrera admitted he was worried that was going to be his best swing of the at-bat.

“I was thinking that was the hit, and now I’m not going to get any more hits,” Cabrera said.

‘I wish the ball was hit to me’

What happened next is one chapter of Pittsburgh sports mythology that led to the city’s greatest chapter of sports infamy.

Like Lind, Van Slyke and Bonds were Gold Glove winners in 1992. After Cabrera’s foul ball, Van Slyke claims he suggested that Bonds adjust his positioning in left field.

“I just told him to move in,” Van Slyke said. “After Cabrera hit that 2-0 foul … as an outfielder, more balls are hit in front of you than behind you, especially on the ground. So my philosophy was, I’m going to give myself the best opportunity to throw the guy out at home plate, especially with two outs because the guy is going to be running on contact.”

Van Slyke said his suggestion was not well received.

“He ignored me and gave me the ‘international peace sign,’” Van Slyke said.

From there, every Pittsburgh fan remembers what happened.

Cabrera strokes Belinda’s pitch into left field. Justice scores to tie the game. Bream chugs around third base. Bonds throws. He’s a bit late and slightly to the first base side of home plate. LaValliere makes a great catch and dives to tag Bream.

It’s too late. Bream is safe. The Braves win and go to the World Series. The Pirates don’t break .500 again until 2013.

“I wish the ball was hit to me because I know, for a fact, we would have gone to extra innings,” Van Slyke insisted.

That said, Van Slyke still believes Bonds takes too much heat for the throw.

“Barry gets an unfortunate rap. It was only off by two feet,” Van Slyke said. “Barry really made a great play. He charged the ball really hard. He had to go to his left, and as a left-handed thrower, and you go to your left it’s kind of hard to throw across your body. So he made a terrific play. It’s just unfortunate that it sailed a little bit up towards the first base line.”

Pittsburgh-born John Wehner was a reserve infielder on the team who had two at-bats in the series. He remembers having a different view of the throw. He doesn’t think it was about Bonds’ depth. Rather, it was about how close to the line Bonds moved after the foul ball.

“Barry moved towards the line,” Wehner said. “He was so close to the foul line. If he is playing him more straight up, he is coming straight in to get that ball. If he is coming straight in, he has a direct path to throw. … But he was coming to his left and in. So he is coming across his body, and that’s when the ball sailed to the first base line.”

As far as the tag, did it beat the slide? You’ll never convince Bream he was out.

“I’ve seen that thing so many times. There’s no way,” Bream said. “Before my foot came up, my heel hit the corner of home plate.”

Just about all the Pirates I interviewed advanced a similar opinion. Van Slyke went so far as to say, “It was close, but he was clearly safe.” And even though there is a small chance that replay review — which didn’t exist in 1992 — might have overturned the call in 2022, Walk has a hard time reconciling how that would’ve settled years later.

“An ending like that, so memorable for two organizations, to end on a phone call to New York? … It’d be a shame, wouldn’t it?” Walk said.

‘I don’t have the heart to look at it again’

Maybe it’s because he’s 77. Or because he eventually won a World Series — with the Marlins in 1997. But for whatever reason, Leyland doesn’t see the use of holding onto the “what ifs.” Not the throw. Not the tag. Not Marsh’s strike zone. Not the pitching change.

“Drabek was fantastic. Belinda actually did a great job. He had the guy struck out. We didn’t get that. If the ground ball is right at somebody, everyone is talking about what a fantastic job Belinda did,” Leyland said.

Belinda didn’t return requests for comment. Neither did Marsh or Bonds. Others like McClendon will talk about the game. He just won’t ever watch it.

“I don’t think I’ve taken out the video and looked at it since the week after it happened,” McClendon said. “I don’t have the heart to look at it again.”

Watching live at the time, it felt like that inning lasted an hour. In reality, with the pitching change, it was about 20 minutes.

The final play lasted nine seconds.

For Pirates fans, the pain has lingered for 30 years.

In today’s Breakfast With Benz podcast, Tim Benz and former Pirates outfielder Andy Van Slyke discuss Game 7 of the 1992 NLCS.

Listen: Tim Benz and Andy Van Slyke talk Game 7 of the 1992 NLCS