Pittsburgh Steelers founder Art Rooney took the most famous elevator ride in NFL history. The Pro Football Hall of Fame has the evidence.

The Immaculate Reception is recognized not only as the play that launched the Steelers dynasty of the 1970s but is considered by many to be the greatest play in NFL history. And the man who deserved to witness it most never saw it.

Rooney, whose club had suffered through four decades of futility, had given up hope with the Oakland Raiders leading 7-6 in the waning seconds of a 1972 AFC divisional playoff game at Three Rivers Stadium. So he headed for the elevator that would take him to the locker room, where he planned to congratulate the players and coaches on a fine season.

There is some dispute as to whether Rooney was on the elevator or waiting for it to arrive when Terry Bradshaw’s desperation pass bounced off Oakland safety Jack Tatum — or off Steelers running back Frenchy Fuqua, if the Raiders’ version is to be believed — and into the hands of Franco Harris. The rookie running back, of course, sprinted for the winning touchdown.

It wasn’t until punter Bobby Walden came bounding into the locker room area that Rooney found out about the improbable ending.

Fast forward to 2001. Three Rivers Stadium is about to be razed as the Steelers prepare to move into their new stadium.

Team president Dan Rooney remembered the significance of that elevator and its place in team lore. So Rooney saved the plate that encased the elevator buttons as well as the plate showing the floor numbers and later donated them to the Hall in Canton, Ohio.

They are among tens of thousands of items stashed in the Hall’s vaults. For more than 60 years, the Pro Football HOF has been the caretaker of NFL history, and its staff of curators and volunteers continues to take in and catalog myriad items.

The Trib recently got a look behind the scenes at the Hall’s archives, and staff members offered insights into how memorabilia is collected and, ultimately, displayed.

***

In a well-lit room deep in the heart of the Hall of Fame, Tim and Cheryl Heslop sit surrounded by jerseys, photos, footballs, documents and other trinkets from the NFL’s past. As two of the volunteers who work in the so-called processing room, the Heslops come in contact with history every day.

This is the first stop for any artifact that comes into the Hall.

“We get to touch it all,” Cheryl Heslop said, lighting up like a child on Christmas morning.

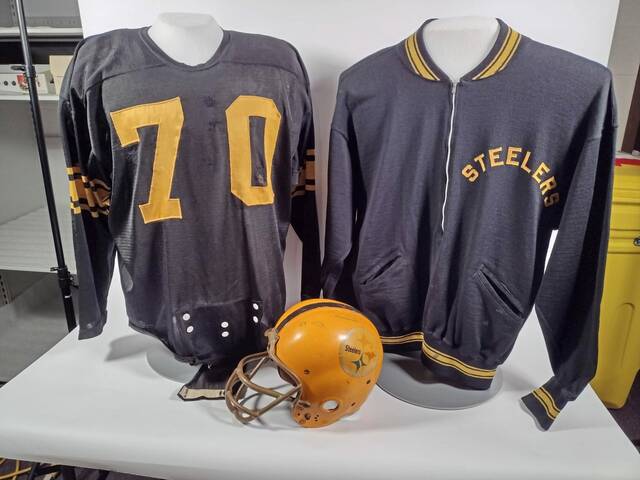

The Hall of Fame, said registrar Brad Collins, has collected more than 40 million documents, 6 million photographic images and 30,000 “3D” artifacts (helmets, uniforms, etc.). At any given time, only a small percentage is on display for the roughly 200,000 annual visitors. To wit: This past week, there were 650 items out for the public to view.

Not all of the memorabilia is confined to Canton. The Hall periodically loans objects to other museums, including the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum at Heinz History Center.

The items are acquired mostly from the general public or, said curator of collections Jason Aikens, a family member of a hall-of-famer. Some items come from the inductees themselves. Collins said former Steelers guard Alan Faneca (Class of 2021) donated helmets he collected from players at Pro Bowls.

And there are more than just football mementos.

Jared Allen (2025) grew up on a ranch and competed in rodeos, so he donated a cowboy hat and lasso. Charles Woodson, who was born with club feet, donated the corrective shoes he wore as a child.

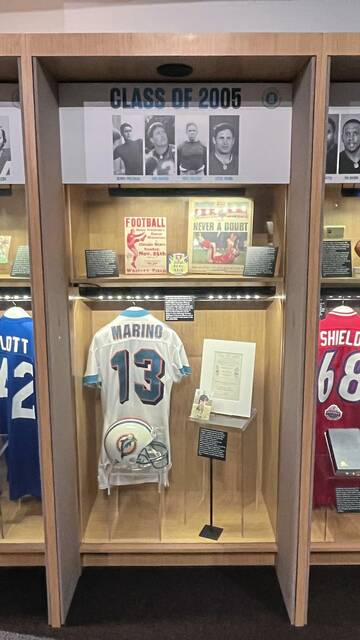

“Whenever somebody is inducted, we have our ‘new class’ gallery, and they come for an on-site visit before they’re enshrined … and we ask them how they would like to be represented,” said Aikens, who has family roots in Ligonier and has been with the Hall nearly 30 years.

Aikens said authentication of items the Hall receives from the general public usually isn’t a problem.

“Most people, if they’re going to donate something, they’re not going to donate something fake,” he said. “If they’re really trying to hold something over somebody, they’re going to try to sell it.”

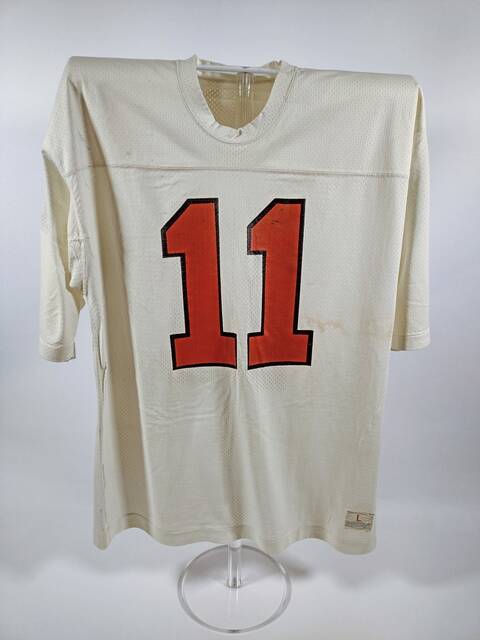

The real challenge, he said, is to make sure the dating of an item is historically accurate. For a pair of shoes donated by former Steelers linebacker Jack Ham (1988), for example, Aikens said the staff had to look at photos to determine what year the shoes were worn.

Not all the objects in the HOF’s collection are associated with inductees. The staff works with the league’s 32 teams — usually an equipment manager or public relations staffer — to acquire items from players who set records or achieve an unusual feat.

Just days after Jacksonville’s Cam Little hit a 70-yard field goal against the Steelers this past preseason, his shoes and jersey were on display.

While the Hall shows only a tiny fraction of its collection, the staff tries to keep things fresh. One way is with the displays that showcase items from Hall of Fame classes that are marking anniversaries. These change annually.

Recently, the HOF had a display honoring the 50th anniversary of Steelers’ Super Bowl IX victory as well as one to commemorate the 1964 NFL champion Browns.

Collins said the Hall also will tailor displays to fans of opponents who are visiting nearby Cleveland. Sunday, the Browns host the Green Bay Packers, so the HOF will highlight Packers memorabilia.

“People who are coming to this part of the country, they want to make the most out of their trip,” Collins said. “So they’ll double dip with us and then the (Browns) game.”

And when the Browns are out of town or on a bye and the Steelers have a home game, it is not unusual for the HOF to feature a Steelers display or one for their opponent.

As might be expected, Western Pennsylvania has been important to the Hall of Fame. According to the Trib’s unofficial tally, 51 of the 382 inductees have ties to the area: 32 who were affiliated with the Steelers at some point in their career, 10 who played at Pitt — only USC, Notre Dame, Ohio State, Miami and Michigan have more hall-of-famers — and nine others who played at Western Pennsylvania high schools.

That keeps visitors from the region flocking to the Canton shrine.

“The fans from Western Pennsylvania have really kept us going over the years and been a reliable source and a reliable fan base,” Aikens said.

***

The elevator plate from Three Rivers Stadium certainly qualifies as one of the more unusual items in the Hall’s vaults. But in terms of oddities, it doesn’t hold a candle to Edgerrin James’ dreadlocks.

“He got tackled in a game, and he got them cut off afterward so he couldn’t be tackled easily,” Collins said of the 2020 inductee. “So they showed up (here) in a box, in a bag.”

There’s also an ear tag from a head of cattle now being raised by former Browns lineman Joe Thomas (2023). It still has some of the cow’s hair attached.

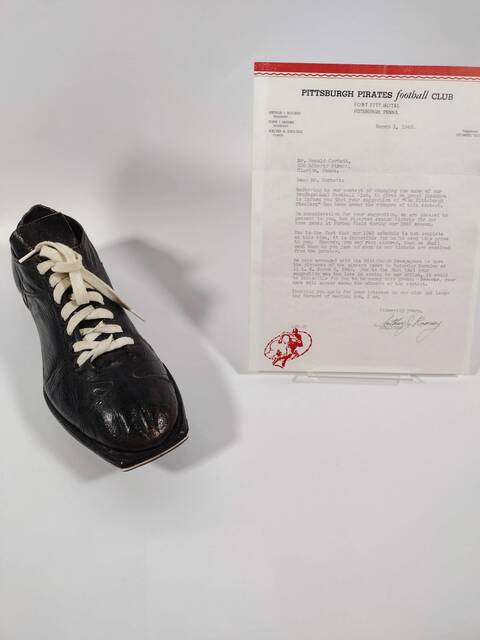

Mostly, the Hall of Fame houses many of the most important historical items that chronicle the evolution of the NFL. Collins and Aikens agree the most significant artifact might be what they call pro football’s “birth certificate,” namely the contract showing William “Pudge” Heffelfinger was paid $500 by the Allegheny Athletic Club, making him the first known pro football player.

Also held in high esteem is the meeting minutes from the 1920 gathering in Canton that formed what would become the NFL. There also is a series of letters between Kansas City Chiefs owner Lamar Hunt and NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle in which the term “Super Bowl” first was used.

Though many of the displays change, one item that has been in view almost continuously since the Hall of Fame opened in 1963 is the sweater Jim Thorpe wore while at Carlisle (Pa.) Indian Industrial School.

Of course, there is a conundrum when it comes to displaying an artifact so precious.

“The best thing for any item is to never see the light of day,” Aikens said. “Any type of light can do some sort of fading, so we try not to keep things on display forever. But some things are just so historic that it’s hard to … like Bart Starr’s Super Bowl I jersey. How do we take that off display?

“There are some things that are just too iconic or too historic to take off display.”

For as much as the HOF has accumulated, curators don’t have everything they want. Pre-World War II memorabilia is much-sought-after. The Hall doesn’t have any artifacts from the NFL’s first game — between clubs from Dayton and Columbus — in 1920, and Aikens is not optimistic anything will surface.

Surprisingly absent are any items from “The Catch,” Dwight Clark’s version of the Immaculate Reception that propelled the San Francisco 49ers over the Dallas Cowboys in the 1982 NFC championship game.

The search for these and other items goes on as the Hall of Fame continues to fill its vaults with memorabilia that keeps fans coming back to learn about the NFL’s history and celebrate its heroes.

“We want to share the collection as much as we can,” Collins said. “We’re collecting for the public’s benefit.”