On the final day of 2010, Pittsburgh was the capital of the hockey universe.

One of the NHL’s tentpole events, the Winter Classic, was being staged on a football field on the North Shore.

Barely half a decade earlier, the idea of any professional hockey games being held anywhere in Western Pennsylvania was far from a guarantee.

Though the Pittsburgh Penguins emerged from bankruptcy in the late 1990s, the overall economics of the entire league and uncertainty over the franchise being able to secure funding for a new arena put everything in doubt.

Speculation of the franchise moving to far-flung outposts like Kansas City, Mo., or Portland, Ore., was rampant.

But a messy lockout that wiped out the entire 2004-05 season eventually led to a new collective bargaining agreement between the league and players that benefited the Penguins greatly.

Then, the even messier business of politics in Pennsylvania was squared away by 2007 and what was initially known as Consol Energy Center opened in August 2010.

Only four months later, the Penguins hosted the Washington Capitals at what was then called Heinz Field on New Year’s Day on national television.

In the lead-up to the spectacle of that game, alumni from both teams held a scrimmage on an overcast afternoon, and the star of that event was Mario Lemieux, an icon for his exploits in a Penguins jersey who eventually became the club’s owner and steered it through those uneasy times at the turn of the century.

After the scrimmage, Lemieux granted a rare bit of media availability and staged a news conference to remark upon the occasion.

Five years after making suggestions of moving to Missouri or Nevada, Lemieux was basking in the Penguins becoming the model franchise of the NHL and hosting such a prominent showcase.

“It’s exciting for the franchise, for the players and, of course, for the fans here that have been supporting us throughout my career since I’ve been here,” Lemieux said. “Anytime you can host a Winter Classic in your own city, it’s very special. And we’ve come a long way. As you know, we struggled for many years before the lockout. We were not able to compete at the level that we wanted to. The new CBA really allowed us to put a great product on the ice and compete with all the (30) teams in the league.

“And of course, the lottery didn’t hurt.”

Winning the 2005 NHL Draft lottery was the product of a handful of painful seasons in the early 2000s in which the Penguins failed to qualify for the playoffs. But they did qualify for some of the best odds in that lottery thanks to a somewhat convoluted system the league devised.

That led to them selecting Sidney Crosby with the first overall selection.

In the two decades since, Crosby has kept the Penguins relevant in ways only Lemieux was capable of when he arrived as the top overall selection of the 1984 draft.

While not always competitive — the past three nonplayoff seasons are evidence of that — the Penguins have continued to matter since Crosby arrived.

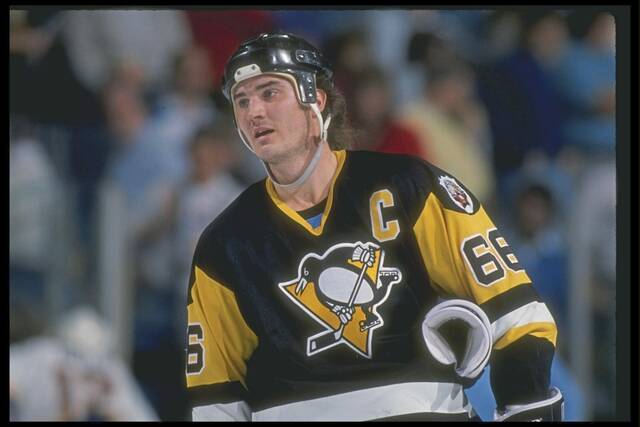

That relevancy is in many ways an extension of what Lemieux established and then cultivated over the 17 years he played for the franchise.

By the time Lemieux retired in 2005, he was far and away the Penguins’ leading career scorer with 1,723 career points.

For the first time since he took over that designation almost four decades ago, Lemieux is not at the top of that list.

Crosby surpassed him and now has 1,724 points.

He reached that mark Sunday during a 4-3 shootout win against the Montreal Canadiens at PPG Paints Arena.

Crosby recorded a secondary assist on a power-play goal by forward Rickard Rakell at 12 minutes, 40 seconds of the first period.

THE HISTORY MAKING POINT!

No. 1️⃣7️⃣2️⃣4️⃣ from the new FRANCHISE LEADER ???????? pic.twitter.com/YdtwNO79hD

— SportsNet Pittsburgh (@SNPittsburgh) December 22, 2025

It was Crosby’s 1,387th career game.

The leader

Lemieux became the Penguins’ all-time leader in points during a 7-3 loss to the Winnipeg Jets on Jan. 20, 1989, at the Winnipeg Arena. Happening on the same day George H.W. Bush was sworn in as president, Lemieux’s accomplishment was hardly a momentous occasion.

In his 336th career game, Lemieux recorded an assist on a goal by defenseman Chris Dahlquist at 13:10 of the second period and broke the mark held by forward Rick Kehoe, who totaled 636 points in 722 contests with the Penguins.

— EN Videos (@ENVideos19) November 24, 2025

Mark Recchi has strong memories of the game — but not Lemieux’s achievement — for good reason.

The speedy right winger scored his first career goal — of a career that eventually led him to enshrinement in the Hockey Hall of Fame — that night.

“I remember the game,” Recchi said by phone in October. “But I didn’t know (Lemieux set the record). I forgot that.

“It wasn’t a very good game. I remember my first goal, obviously. I guess we would have probably known after if he (set the record), but I don’t remember that for some reason.”

The record was more of a footnote than a celebration, especially since Lemieux tied the mark as he reached a more notable milestone earlier in the game by opening the scoring with his 50th goal of the season (in only his 44th game).

— EN Videos (@ENVideos19) November 24, 2025

Later in the contest, Lemieux also had a role in Recchi’s history by setting up his first goal.

— EN Videos (@ENVideos19) November 24, 2025

“I don’t know what I was doing on the ice with Mario at the time,” quipped Recchi, a fourth-round draft pick (No. 67 overall) in 1988. “Mario made a great pass to me. I was driving the net, and I chipped my goal in.”

Recchi eventually earned a steady role on Lemieux’s line, particularly during the 1990-91 season when the franchise won its first Stanley Cup title.

“I always said, the great thing is there is never a bad pass to Mario because he could pick up anything,” Recchi said. “He’d make us look good. I’d send one, and it would be a terrible pass. He’d pick it out of the air, and he’d go down and he’d score. I’d be like, ‘Well, that’s a hell of an assist I just got.’ He was just incredible to play with. In (the 1991 playoffs), he was such a two-way force. He defended. Played two-way hockey unbelievably well. It was so much fun to be a part of.”

Ryan Malone had plenty of fun at that time as well.

The son of former Penguins forward-turned-executive Greg Malone, Ryan Malone grew up around Lemieux and company.

Before the team’s celebration upon winning the Stanley Cup again in 1992, Malone was granted some exclusive company.

“It was in the back of the bus for the parade at Three Rivers (Stadium), me and my brother,” Malone said. “There was no other seats on the bus. We’re all the way in the back. Mario was generous to let us sit back there.

“Mario. It was crazy to be on the back of (that) bus as a 13-year-old.”

Hockey town

A little more than a decade later, Malone, as a 24-year-old, became one of the first natives of this region to reach the NHL, and he got to do so as a power forward with the Penguins, who drafted him in the fourth round (No. 115 overall) in 1999.

Malone was a trailblazer for Western Pennsylvanians who dreamed of reaching the NHL, as he did in 2003. And his starting point as a hockey player was largely put in place by Lemieux, who caused the sport’s popularity to blossom in the region.

“There were like three rinks in the 1980s,” said Malone, who grew up in Upper St. Clair. “Them winning the Stanley Cup in the early 1990s definitely put hockey on the map in Pittsburgh. Obviously, it’s still a football-dominant town, but it was really the growth of the hockey rinks. There was nothing really around.

“I remember our high school practices were at that Bridgeville rink where there (were) brick boards and a caged fence. I don’t even know if parents would allow kids to skate there anymore, but that was the only ice there was around. So, his effect, definitely, now you can see how many rinks from that time until now. That shows the impact he had on the community, bringing those championships.”

Lemieux laid that foundation while Crosby has expanded upon it, particularly with his Little Penguins Learn to Play Hockey program.

Utah Mammoth star forward Logan Cooley, a native of West Mifflin, is a product of that endeavor.

“That’s the greatest impact is what you’re having on the community,” Malone said. “Mario, to this day, I think his foundation has donated something like $40 million back to the community. Sid’s learn-to-play program, what a great story with Logan Cooley.

“I’m sure they love all their trophies and everything, but their greatest impact is probably how they’ve affected people around them. That’s where you see both of them impact so many lives in a positive way just by being true to themselves.”

Crossing paths

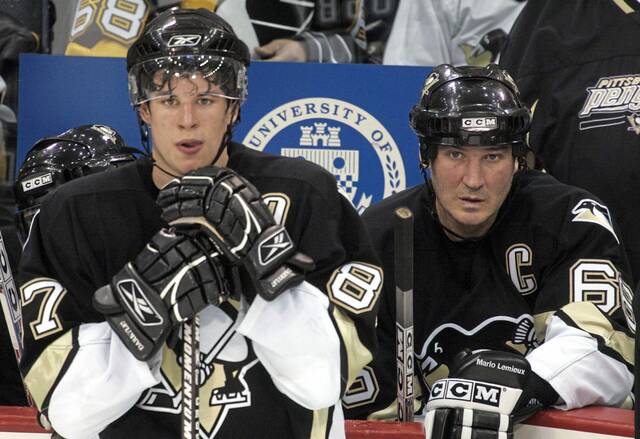

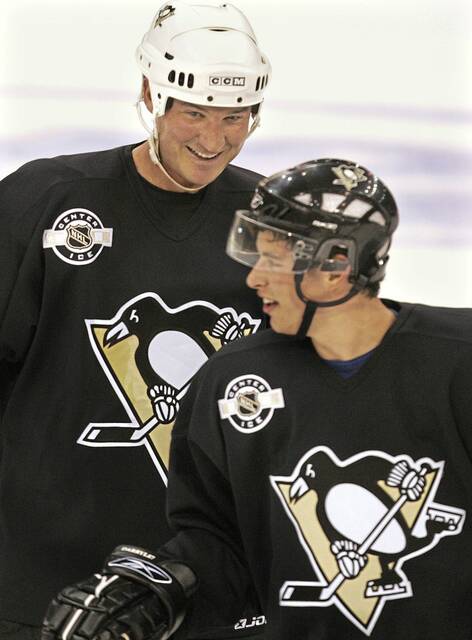

Crosby arrived in 2005, and he was one of three No. 1 overall draft picks in the Penguins’ nest.

He joined goaltender Marc-Andre Fleury (2003) and Lemieux (1984).

Lemieux was still the most important component of the present. But Fleury and Crosby, especially, were the future.

“I knew (Crosby) was coming,” said Recchi, who re-signed with the Penguins in 2004. “Pretty excited when we got that first pick.

“When you get that young stud — just like when it changed with Mario — it just brings energy, it brings excitement. Then it follows up with Fleury and (Evgeni) Malkin and (Jordan) Staal and (Kris) Letang, it follows up with those guys adding to a stud like Sid — and they’re all studs in their own right — you know he was special, right from the moment he came in. As a person and as a player.”

The Penguins won the highly anticipated draft lottery that led to them selecting Crosby on June 22, 2005. That event was treated like an impromptu holiday in Pittsburgh.

“It was the summer, we were golfing and people were going crazy,” Malone said. “Me, just coming into the league, I was like, OK, it’s another young guy. You always hear that. … Everyone usually hypes up those top picks.

“Then when you saw Sid on the ice in camp … there was another gear this kid has.”

Lemieux’s gear had slowed down by this point in his career. He had turned 40 as the season opened and far too many ailments, such as a serious back injury and Hodgkin’s lymphoma, had taken their toll in ways that extended well beyond his effectiveness on the ice.

But his brilliance could not be dulled.

“In practice (during the 2003-04 season), we’d do these one-on-one drills,” Malone said. “The forwards are on the goal line, defense on the hashmarks. The forward is going to go along the boards, then the (defensemen) could kind of cut over center ice to angle off. And anytime (the defenseman) would cross his feet over, Mario would do his move where he would put the puck through his stick and feet and jump around him. He was just burying (defenseman) Drake Berehowsky both times.

“Then (Berehowsky asked), ‘What am I supposed to do?’ talking to (an assistant) coach. Then, (the coach would say), ‘Don’t go over there.’ So, they just let Mario come down hard and he would just take a slap shot from the outside instead of dancing around. He was just so smart. He (said), ‘If I can just wait for the (defensemen) to cross over, you’re waiting for that crossover, then you’re hopping the other way.’

“He had these little things. … The details with which he saw the game were so impressive with how smart he was (at) anticipating.”

Lemieux and Crosby shared that attribute. But they were clearly different in a variety of other ways.

The elegant Lemieux was a towering 6-foot-4 and 230 pounds, while the frenetic Crosby is a more compact 5-11 and 200 pounds.

“On the ice, they’re both very competitive,” Recchi said. “Their competitiveness is so high. You watch Mario play through back injuries. You know he doesn’t have to do that. It just shows you how competitive he is. He wanted to be on the ice. He wanted to play well. He wanted to help the team. They’re different players. Obviously, Mario is a lot bigger. Sid is just under 6 feet. The physical part is different. But Sid’s physical maturity was incredible.”

Their methods of viewing the ice were divergent.

“They saw the game a little different with angles and creating space for one another,” Malone said. “Mario, especially with the power play, was the perimeter pass guy. You never see any guys shoot that one-timer from the goal line ever, or anymore rarely, which I loved. Sid was definitely more, ‘Hey, go challenge that defenseman one-on-one.’ ”

Bodies of work

One area Crosby has easily enjoyed a considerable advantage over Lemieux in is health.

While Crosby did lose parts of two seasons because of chronic concussion woes in the early 2010s, his maladies weren’t quite as severe as Lemieux’s.

A herniated disk in his back required surgery during the 1990 offseason. And cancer took an incalculable toll beginning in 1993. His recovery from Hodgkin’s lymphoma led to him sitting out the entire 1994-95 season and had a role in his first retirement in 1997.

An irregular heartbeat led to his permanent retirement in 2006.

“His back, there would be days he couldn’t tie his skates up and he’s going out there and playing,” Recchi said. “You could just imagine if he didn’t have that and those issues, what he could really have accomplished.

“It’s incredible what he accomplished.”

A lot of those accomplishments happened in an era that was far different with regard to training and diet.

And lifestyle.

Lemieux entered the NHL when players still smoked, a habit he engaged in early in his career.

In contrast, perhaps the most dangerous vice Crosby is prone to might be peanut butter cups (the organic ones).

Crosby’s longevity has been no accident.

His commitment to — obsession with, really — his physical well-being has allowed him to remain one of the NHL’s most dominant players as he approaches his 40s.

“Sid was talking about gut health in 2006 or 2007,” Malone said. “I go to (Vail, Colo.) with his (training) group. And he’s talking about gut health. I have no idea. ‘OK, sure, bud. Whatever you’re talking about.’ They’re sprinting up the mountain. I’m carrying all the beers up the mountain, taking my time.

“It wasn’t until five years ago that I understood gut health, 90% of our serotonin, our ‘happy chemicals,’ are produced in our gut.

“Sid has gone two decades long. It makes sense. He was 19. That’s how detailed he was of understanding his body, what to put in it at the right times.”

To this day, Crosby is routinely one of the final players off the ice.

Not just after practice. But after a season as well.

“There’s a reason why he’s still so good at this age,” former Penguins defenseman Brian Dumoulin said. “He doesn’t take time off. At the end of the season, he’s skating two days after. A couple of summers ago, Sid was around a lot, so me and him skated a lot together.”

Though he is certainly blessed with natural talent, Crosby is still here for another reason.

“(Former Penguins forward Colby Armstrong) mentioned to Sid, ‘Oh you’re just so lucky,’ ” Malone recalled. “You’re born with this gift. Sid was like, ‘(Expletive) you. I work at this.’ Sid’s tenacity and work ethic is just beyond description.”

Carrying things

Another commonality between the two is the burden of being the face of the franchise, if not the entire NHL.

That responsibility was born out of their adroitness on the ice as much as their presence off it.

“The one thing they have in common is they treat everyone with respect and dignity,” Malone said. “They understand everyone is part of a team. They understand it takes everyone to have success. That goes to the equipment (staff) to the guys running the Zamboni. They want to make everyone feel a part of the team. They bring people together. As a player on the ice, they raise your level of commitment to the team and to your personal career just from their work ethic.”

Crosby was remarkably mature when he debuted as an 18-year-old and was ready to meet the daunting demands of being the “next one.”

But he got some good guidance from the previous one.

“They can’t really have that normal life,” Malone said. “Mario, for sure, probably (said), ‘This is maybe what I did wrong or could have done better as a kid.’ I’m sure living with Mario, he got wrapped up in the way he’s preparing for games and the routine of things. I couldn’t imagine how beneficial that was for Sid to learn from one of the greatest of all time.”

After Lemieux’s retirement in 2006, Crosby succeeded him as captain in 2007.

“He’s always been a quiet leader but also a very good leader,” Recchi said. “You see how he practices. You see how he trains. And obviously, when he speaks, you listen. It was just taking that next step for him. Mario was the same way. Mario was just a really quiet leader. Different people, but they were similar in that aspect.”

Comparables

It’s probably safe to assume Lemieux’s place in franchise history will remain secure for however long the Penguins exist in Pittsburgh.

Still, seeing a “No. 2” next to his name on the list of the franchise’s leading scorers for the first time in 36 years is a bit jarring.

But it illustrates what Crosby has done in his 21 years wearing the Penguins logo.

“I think the fans don’t understand how lucky they’ve been the last four decades, having the elite of elite players being here,” Malone said. “What a rare, awesome thing that would probably never be done again with how sports are being done now. With Sid being No. 1, he earned it, obviously. He deserves it. Mario is always going to be Mario. And Sid is going to be Sid, which is a great thing.

“Two amazing hockey players. Pretty cool.”

As for who is the better player, Crosby’s thoughts on the matter are succinct.

“He’s still number one in my book,” Crosby said after Sunday’s game. “I don’t think you can put a stat line or a number on what he means to this team and to hockey. In my mind, he’s still number one.”

Lemieux’s ruminations on any comparisons are a matter of speculation, given how private he has been in his post-playing years.

But on May 30, 2009, before the start of Game 1 of the Stanley Cup Final, Lemieux held a rare news conference at Joe Louis Arena in Detroit and remarked on the then 21-year-old captain of his team that would eventually win the franchise’s third championship a few days later.

Lemieux’s thoughts on Crosby that day remain relevant today.

“He’s a lot more mature than I was at (that age),” Lemieux said. “He was a lot more mature at 18. He’s a special kid. He’s a better player than I was at the same age, for sure. Some of the things that he does on the ice — his strength, skating ability — (are) incredible.

“His passion for the game and his will to be best each and every shift, his work ethic, he’s got it all.”