After 60 years of dedicating his life to coaching and mentoring youths, Jimmy Gregg is not only synonymous with Greenfield Baseball Association but the neighborhood itself.

“He is Greenfield baseball,” said Emily Pocratsky, whose children play in the league and who is the vice-president of the T-Ball league. “He loves Greenfield and he loves the game. For him, it’s about the kids.”

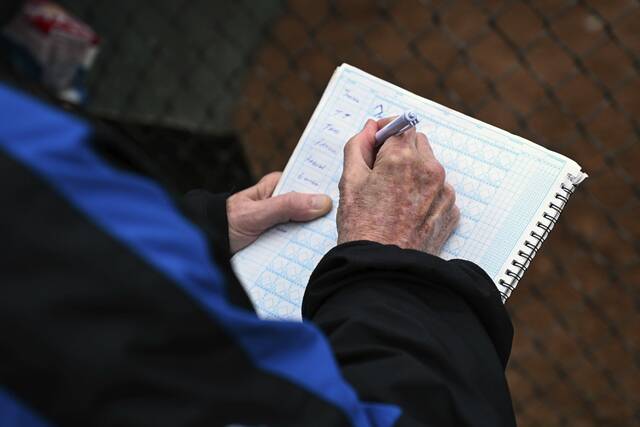

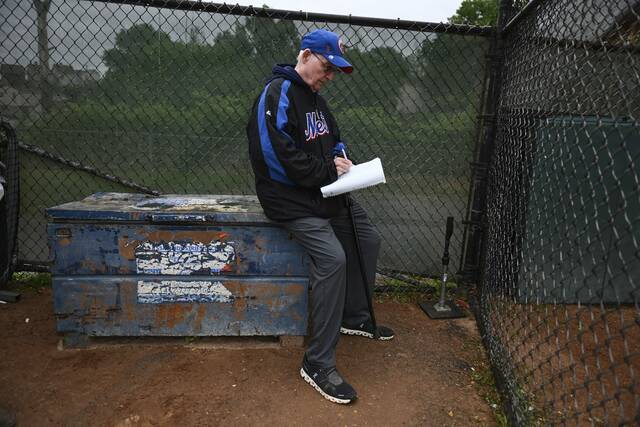

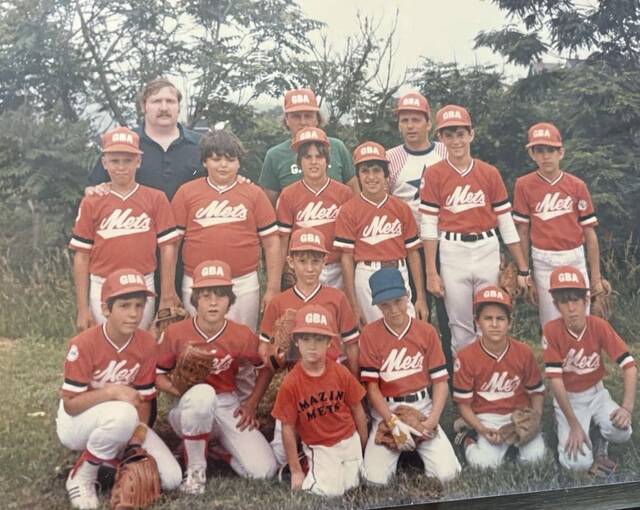

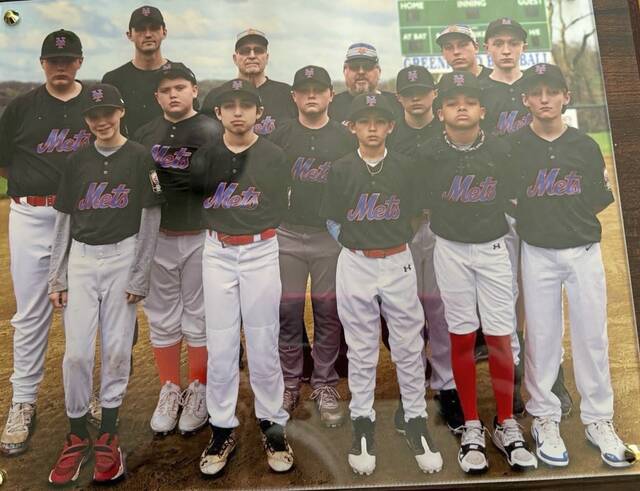

Coaching has been a labor of love for Gregg, 73, who is retiring at the end of the season because of his health. His Little League Mets finished with a 9-3 regular-season record. The team won a best-of-three playoff series to reach the Greenfield Baseball Association Little League World Series, which begins later this week or next week against the winner of a series between the Twins and the A’s.

As Gregg nears the final days of his coaching career, he has been honored in his hometown. A street in Greenfield was renamed Jim Gregg Place. A mural of him was painted on the dugout at Bud Hammer Field by Justin Kichi. Gregg has thrown out several ceremonial first pitches, including one at PNC Park before the Pittsburgh Pirates played the Miami Marlins.

More important to Gregg is the family his coaching has created. He receives text messages, phone calls and visits from former players and attends their high school, college and professional games.

Mets player TJ Mihailoff, 12, calls Gregg an inspiration. His father, Tom Mihailoff, said the community environment Gregg has built makes it a positive experience, and he cares about every kid. His grandmother, Anne Mihailoff, said playing for Gregg has built TJ’s confidence.

“He helps us with hitting, and he is always positive,” TJ said. “Sixty years is a long time. He makes Greenfield baseball better. This is the only team I want to play for.”

As he was being interviewed by TribLive, Gregg received a congratulatory text message from a former player.

“This,” Gregg said, “is why you coach.”

‘Level of commitment unmatched’

A bout with cancer required an operation on Gregg’s hip. He is cancer-free, but he has a spinal issue that affects his right leg, so Gregg uses a cane for stability. That has limited his ability to do one of his favorite things in baseball, the daily ritual of throwing batting practice to players.

“I used to be able to throw hundreds of pitches in batting practice,” Gregg said, “but I just can’t anymore.”

Gregg has delegated those duties to his assistant coaches Bryan McCann, who now plays for Point Park; Mark Pfleger, an assistant baseball coach at Allderdice; and Ryan White, a three-sport athlete at Brashear.

McCann recalled how, when he played for the Mets, Gregg could throw hundreds of pitches in the batting cage at Hammer Field.

“It would be dark, and he would still be throwing pitches,” said McCann, whose father, Chris McCann, and Mike Waugaman also help coach the Mets.

Adds White: “His presence, and his level of commitment are unmatched.”

That’s a lesson his players learned from Gregg: the importance of giving and not expecting anything in return.

Gregg, who advocated to get lights for night baseball, said he plans to stay involved in some way.

“He set the bar high,” said Greenfield Baseball Association president Mike Terlecki. “I want to keep this going for him. This is his baby.”

And his former players have become extended family for Gregg, who has never married and has no children of his own. His twin sister, Jane Boback, has watched how he provided a positive influence on hundreds of young players over the decades.

“His players and their families have been there for him, too,” she said. “It’s a beautiful relationship.”

Gregg credits Paul “Ace” Gorman, who was the recreation leader at Magee in Greenfield when Gregg was growing up, with instilling in Gregg the love of sports and the desire to coach.

“I lived down Magee field,” Gregg said. “Ace was so good to all of us kids. He taught me the importance of paying it forward.”

Craig Rafferty emphasized how Gregg values faith and family, including his players. Gregg has served as a Confirmation sponsor for 21 former players, most recently for his assistant coach White.

“Jim Gregg is more than sports,” Rafferty said. “He does so many behind-the-scenes things that people don’t know about. He is a father figure, and I can tell him anything.”

Coaching about life

Gregg started coaching at age 14, mentored by Mike Palmieri and Don Horgan. For nearly three decades, Gregg coached with John Sicoli. Coaching became his passion project but not his entire life.

Gregg continued coaching while working at Allegheny County Jail in Downtown Pittsburgh for 32 years, 22 as chief deputy warden. Overseeing the inmates instilled in Gregg the importance of guiding young people in the right direction. He co-founded Greenfield Organized Against Drugs with Dr. Bernard Bernacki and is involved in the annual Greenfield Community Awards Dinner.

“You give respect, you get respect,” Gregg said. “It’s all about teaching players about going in the right direction and not just around the bases or shooting at the right hoop. I hope I have led them down the right path in life.”

For Gregg, it’s not just about winning. It’s about building character.

That wasn’t lost on Pirates director of broadcasting Marc Garda, who played for Gregg with the Mets. When the Pirates invited Gregg to throw out the first pitch against the Marlins, Greenfield turned out. Garda said 300 people bought tickets in the left-field bleachers to celebrate Gregg’s final first pitch.

“The thing that stands out to me is that he always treated everyone exactly the same,” Garda said. “It was special to play for him. I learned from (former Pirates player and broadcaster) Steve Blass that the one thing you can give in this world is your time, and no one does that better than Jim Gregg. And the number of lives he touched … you can’t put a value on that.”

Mike McCarthy can put a value on what he’s learned from Gregg. He has a Super Bowl ring to show for it.

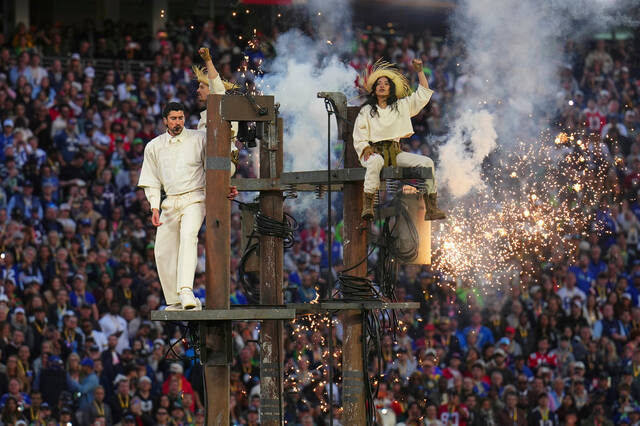

A Greenfield native, McCarthy recalled the excitement of playing in a T-shirt league as a 9-year-old when his team won the World Series against Gregg’s team. Decades later, McCarthy would beat Mike Tomlin’s Steelers in Super Bowl XLV.

McCarthy counts his father, Joe McCarthy Jr., and his Greenfield father-figure coaches for inspiring his career path. That list includes Joe DeIuliis, John Varley, Marty “Roundball” Coyne, Jerry “J.D.” Dusch, Bob Roche, Ted Karabinos and, of course, Jimmy Gregg.

McCarthy coached the NFL’s Green Bay Packers to the Super Bowl XLV championship. More recently, he was the coach of the Dallas Cowboys. No matter where McCarthy coached, Gregg was a fan who wore that team’s colors, even when they played the Steelers.

“Jimmy Gregg is so well respected,” McCarthy said. “I realize from a coaching perspective, Jim Gregg pulls that competitive spirit and toughness out of you immediately. He means a lot to my entire family. Seeing his impact on so many people is one of his many qualities that make me proud to be from Greenfield.”

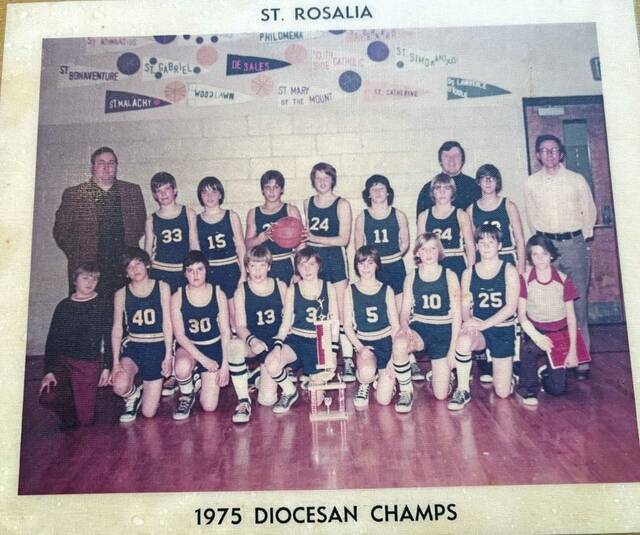

McCarthy played on Gregg’s basketball team at St. Rosalia Grade School in 1975, when the team finished 39-1 and won the Pittsburgh diocesan championship. Gregg coached at St. Rosalia for nearly five decades, which included being involved in the Diocesan Roundball, until the school closed in 2018.

Former player Kevin Kelley said Gregg found a place for Kelley’s younger brother, Timmy Kelley, to be a manager and scorekeeper on that 1975 championship basketball team when he wasn’t able to play because of a heart condition.

“Jim cares about what is most important in life,” Kevin Kelley said.

McCarthy recalled Gregg bringing the basketball team to Children’s Hospital on Christmas Eve to visit Timmy Kelley, who died the following May. Gregg and the players were pallbearers at the funeral.

“Those moments have stayed with me,” McCarthy said. “Jim Gregg is about more than wins and losses. He coaches about life. There needs to be a movie made about him.”