In a football sense, Jackie Sherrill grew up at the knee of Bear Bryant. His cradle was the SEC.

He played fullback and linebacker from 1962-65, before serving as a graduate assistant for the legendary Alabama coach in 1966.

When Sherrill walks into Neyland Stadium in Knoxville, Tenn., on Saturday — he’ll be Pitt’s honorary captain for the game against Tennessee, its first in an SEC venue in 38 years — he can say with pride, “I’ve been here before.”

This time, the 77-year-old retired coach won’t be carrying wire cutters.

The game has been anointed the Johnny Majors Classic in honor of the former Pitt and Tennessee coach, who led the Panthers to the national championship in 1976. Majors wanted to be there for the third all-time meeting between his two beloved schools, but he died last year at the age of 85.

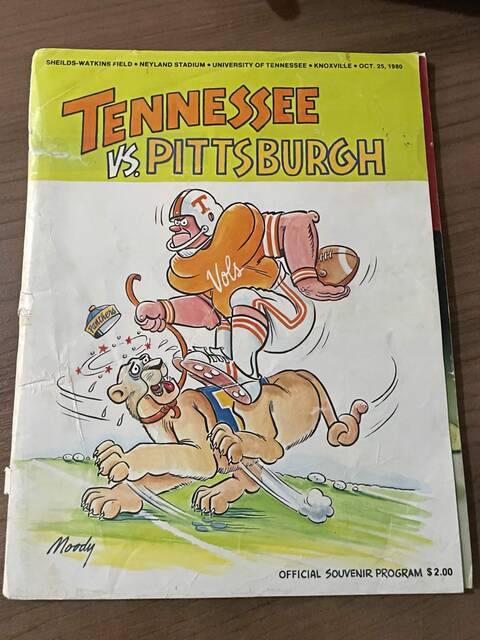

Pitt and Tennessee have met only twice, with Pitt beating Majors both times — 30-6 on Oct. 25, 1980, and 13-3 on Sept. 5, 1983. Both games were played in Knoxville. SEC teams don’t do much traveling north of the Mason-Dixon Line. When Tennessee plays at Heinz Field next year, it will be the first time an SEC team visits Pittsburgh.

Sherrill was Pitt’s coach in 1980, having replaced Majors in 1977 when he left for Tennessee, his alma mater. Sherrill had coached with Majors at Arkansas and under him at Iowa State and Pitt. Upon Majors’ death, Sherrill referred to him as his “father figure.”

Friends forever, the two men had dinner together the night before the game.

“We didn’t give away any secrets,” Sherrill said when contacted this week. “Coach Majors and I had a very good relationship. It got a lot stronger as we retired and got older.”

Sherrill downplayed the coach vs. pupil angle.

“My comment then was ‘Coach Majors and I are not going to play the game. If we were going to play, I don’t know if anybody would show up.’ ”

Former Pitt safety Tom Flynn, a Penn Hills native, said his teammates had bigger plans. Pitt was 5-1, ranked No. 12 in the nation and on its way to an 11-1 finish.

“There was a lot of discussion in the papers about the Jackie Sherrill/Johnny Majors rivalry,” Flynn said. “It seemed like it was as much about the coaches as it was about the two teams that were playing that day.

“We were working toward trying to go undefeated the rest of the way and in doing so we could try to achieve, maybe, a national championship and also give Jackie something to smile about.

“I know Jackie wanted one really bad. We all wanted one for him. As we know, it didn’t quite turn out.”

Flynn said he liked Sherrill from the first time they met.

“He didn’t put a lot of B.S. in front of me,” Flynn said. “He was straightforward and cut to the chase. He told you what you needed to do and then it was up to you whether or not you wanted to do it.”

Sherrill believed his team was well-prepared for the game. Nothing surprised him, especially not the wall of noise from the crowd of 94,008. “I remembered that from years ago as a player (at Alabama),” he said.

Sherrill said the sidelines were lined with huge speakers, the kind you might see at a rock concert. There were 10 on each side, every 10 yards.

“On the home side, they faced the stands. On the visitor’s side, they faced the field. You couldn’t hear on the sideline,” he said.

It was common practice then — as now — for lawmen to stand by the side of college coaches to help them get through crowds, especially after a game.

Sherrill employed Allegheny County Sheriff’s Deputies Johnny Parker and Ray Goga, who became friends with the coach and grew closer to him than almost anyone in the Pitt athletic department.

Sherrill decided to put them to work.

“I gave Parker and Goga wire cutters before the game,” he said. “I told Ray to cut those speaker wires. He did. (Stadium workers) fixed them and he cut them again right before kickoff.”

But Sherrill wasn’t finished with his gamesmanship. Stadium officials wanted Pitt players to run onto the field at a certain time. Sherrill refused.

“(He said), ‘I ain’t doing it until (the Tennessee players) come out because you can’t cheer and boo at the same time.’”

Not long after kickoff, Pitt asserted its dominance.

Rick Trocano replaced Dan Marino, who had been hurt the week before against West Virginia, and orchestrated an offense that rang up 489 yards (237 through the air). He also ran 31 yards for a touchdown on a busted play.

Perhaps Trocano was motivated by another one of Sherrill’s tricks.

Tennessee quarterback Jeff Olszewski came from Parma, Ohio, only 3 miles from Trocano’s hometown of Brooklyn, Ohio. In his book “Golden Panthers Pitt’s 10-Year Affair With Football Prominence,” author Sam Sciullo Jr. writes that before the game, Sherrill walked up to Trocano and told him Majors considered the Parma kid a better prospect. Of course, it wasn’t true, but the story sure didn’t hamper Trocano’s efforts that day.

As Pitt seized control in the second half, the crowd became much quieter. “They were leaving their seats with seven minutes to go,” Flynn said.

Defensively, Pitt dominated, giving up only a 100-yard kickoff return to Willie Gault and just 12 first downs and 177 yards of total offense.

“It seemed like a lot of things we worked on worked,” Sherrill said.

Pitt’s 1980 team might have been its most talented, with 12 players drafted into the NFL in 1981, including Hugh Green, Randy McMillan and Mark May in the first round. Offensive tackle Jimbo Covert and backup cornerback Tim Lewis turned into No. 1 draft choices in 1983. Reserve defensive tackle Bill Maas became an All-American in ‘82 and a first-round pick in ‘84.

Pitt was 11-1 for three consecutive years from 1979-81, and Sherrill said the Panthers would have won two national championships if the “dumb head coach had been smarter.”

The only loss in 1980 was to Florida State, 36-22, two weeks before the Tennessee game. Sherrill said he allowed players to mingle with their families at the hotel during the day before playing the Seminoles at night.

“We have a lot of players from the south,” Sherrill said. “I was allowing the parents, maybe their brothers and sisters. I didn’t realize it was first, second and third cousins who showed up.”

Nonetheless, Flynn has only good memories of playing on two of those 11-1 teams.

“The further away it gets, the more special it seems to be. It doesn’t get old,” he said.

“When you see guys I played with get into the Hall of Fame, it resonates how good they were as football players and for the most part, they were also that good at being teammates.”

Echoing the current Pitt team’s We Not Me battle cry, Flynn said, “Not a whole lot of individualism back in those days. We tried to stick together and make sure that it was us against them. No matter who the them might be, we knew who the us was and that was the guys in the locker room.”