Johnny Majors, a devoted son of the South whose single act of reviving Pitt football endeared him to a very northern city, died Tuesday night in Knoxville, Tenn. He had turned 85 on May 21.

Jackie Sherrill, who followed him from Iowa State to Pittsburgh and became his eventual successor at Pitt, said Majors died in his sleep Tuesday night on his back porch.

Sherrill said he spoke to Majors by phone Sunday night.

“(He was in) great spirits,” Sherrill said. “He was sitting on his back porch, having a beverage and we talked for over an hour.

“The last things (said) were we need to see each other and we made plans either for him to come to Texas or for me to come to Tennessee and spend time with each other.

“It was a shock to me. He talked about how good a shape he was in and how he was feeling really well. We laughed and talked.

”I was talking to his son, John Ireland, (Wednesday) morning. He was sitting on the back porch (Tuesday) night and fell asleep and didn’t wake up.”

“He spent his last hours doing something he dearly loved,” Majors’ wife, Mary Lynn Majors, told Sports Radio WNML, “looking out over his cherished Tennessee River.”

Majors, a member of the College Football Hall of Fame, was inducted into the Pitt Athletics Hall of Fame in 2019. He will be joined there by Sherrill this year.

John Majors, 1935-2020.

— Pitt Football (@Pitt_FB) June 3, 2020

He led us to our greatest glory and changed Pitt forever.

Thank you, Coach. Rest in peace. pic.twitter.com/bPs4OEoQXW

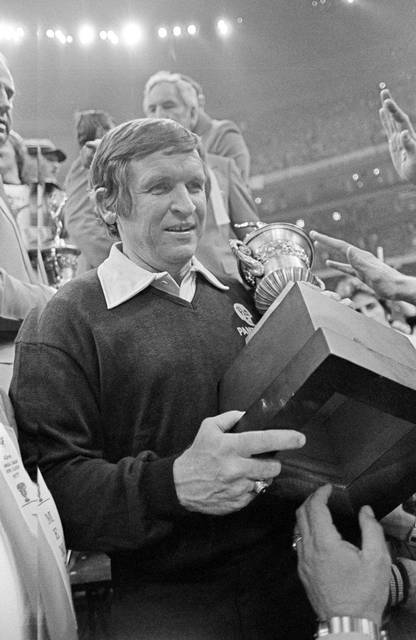

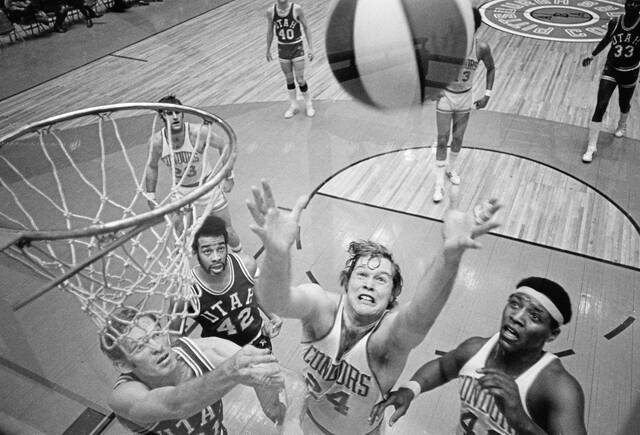

Hired as the Pitt coach in December 1972, the former Tennessee tailback and Heisman Trophy runner-up inherited a 1-10 team from the Panthers’ ninth straight losing season. He immediately injected life into the program, hiring top assistants and loading up on recruits. The Panthers were 6-5-1 in 1973. They won seven games the next season and eight the next. In 1976, Majors’ fourth season, Pitt went 12-0 and won the national championship while producing a Heisman Trophy winner, senior running back Tony Dorsett.

Rest in Heaven, Coach. Words could never express what you meant to me. Catch you on the other side.@Pitt_FB @PittTweet pic.twitter.com/4QgM7mA2u2

— Tony Dorsett (@Tony_Dorsett) June 3, 2020

With its first national championship since 1937 and ninth overall, Pitt restored a rich football tradition and emerged as a worthy college counterpart to the Pittsburgh Steelers, who were building an NFL dynasty. Majors, the architect, stood taller than the Cathedral of Learning.

And then he left. Lured by his alma mater and the only other job he said he would take, the Lynchburg, Tenn., native headed home to coach the Tennessee Volunteers. It was not entirely pleasant. The later years were better than the early ones, but disenchantment among too many fans and boosters, and conflicts with university officials led to his forced resignation during the 1992 season, his 16th, less than a month after undergoing heart surgery.

Majors promptly returned to Pitt, his second home, and its familiar surroundings. But much had changed, including academic standards and rules governing scholarships and rosters. No longer could he haul in nearly 90 high school recruits and junior college transfers, as he did in that first season two decades before.

Pitt football was not the same as he left it. After Majors left for Tennessee, he turned the program over to his former assistant, Sherrill, and good times continued. Sherrill left for Texas A&M in 1982 and, despite some winning seasons during the next decade, the program fell into disrepair.

Majors sought to again ride to the rescue, failing to heed Sherrill’s warning not to take the job. Majors returned in 1993 and endured four years of losing before turning in his whistle for an administrative job with the university. In 2007, he again returned to Tennessee to stay, having made an indelible impression on the Steel City and its environs.

Dorsett, who went on to a Hall of Fame NFL career with the Dallas Cowboys, said of Majors in a 2014 interview with the Trib, “He brought Pitt football back to a national presence. When he came in he recruited a zillion players and ran some players off and brought the program back up. It was breath of fresh air.”

The late Pitt sports information director and TV personality Beano Cook called Majors “the most beloved southerner of all time in Pennsylvania.”

Majors was hired after five years at Iowa State, where he improved the program as a first-time head coach. He was 37 when he arrived in Oakland bent on fixing a program in such bad shape that some believed drastic action might ensue if Majors failed.

“What I recollect hearing is they were gonna give it one shot and if it couldn’t be turned around they were gonna drop a level, or drop football,” Sherrill, who served as Majors’ defensive coordinator and assistant head coach before becoming head coach at Washington State in 1976, told the Trib.

True or not, the situation was dire. It wasn’t just the losing. Majors once described the facilities as “atrocious.” He reportedly said, “Is that all there is?” when first inspecting the Panthers’ equipment room.

But chancellor Wesley Posvar, athletic director Cas Myslinski and some prominent donors ensured that Majors would have the necessary means. The school spent freely to upgrade facilities and provide Majors with what amounted to an unlimited recruiting budget, with scholarships to match. Pitt tight end Jim Corbett, part of Majors’ first recruiting class, cited the figures, 73 freshmen and 13 junior college transfers.

“I don’t know how you get that past the accounting department,” Corbett told the Trib. “It took a lot of stretching of resources.”

Majors was familiar with big recruiting classes. At Tennessee in 1953, he was among 127 freshman recruits.

Later in 1973, the NCAA instituted what some have called the “Majors Rule,” drastically limiting rosters and scholarships. Majors and others debunked the label, saying the plan was in the works before he arrived at Pitt. Regardless, Majors and his staff took full advantage while they could.

“We didn’t know any better,” said Sherrill, who accompanied Majors from Iowa State.“We just put our heads down and our rear ends up and started recruiting.”

The key recruit was Dorsett, a tailback from Hopewell High School. A bit undersized, he was incredibly fast and elusive. Majors made Dorsett a top priority. The first time he visited Hopewell, Sherrill said, the principal told him to leave because the previous Pitt staff was not particularly enamored with Dorsett. The hard-nosed and stubborn Sherrill, who played for Bear Bryant at Alabama, was undeterred.

“I came back every day and we became friends,” Sherrill said. “I was there all the time.”

Quiet and introverted, a self-described “momma’s boy,” Dorsett preferred to attend college close to home and was looking for any reason to attend Pitt, despite its problems. He found it.

“Johnny Majors and Jackie Sherrill did one heck of a job recruiting me,” Dorsett said. “Every time I walked out the door it seemed like there was a Pitt coach. I kind of befriended those guys. I trusted them. I could have gone anywhere in the country, but I trusted them.”

Baked goods might have helped, too. Sherrill’s mother would send her son homemade pecan pies, and Sherrill would bring them to Dorsett’s mom.

Majors set the tone with his first preseason camp at Pitt-Johnstown, where the heat was brutal and the contact relentless. There was a high attrition rate, but it was disregarded and likely preferred because of all the players on hand.

“I think we took five buses to camp,” Sherrill said. “I think three came back.”

Al Romano, a freshman recruit from Syracuse, told the Trib that he called his dad and told him he was thinking about quitting.

“He pretty much ran half the team off by the end of those workouts,” recalled Romano, who stuck it out and became an All-American defensive lineman.

“There was a lot of hitting,” Dorsett said. “They had a lot of players and they were trying to weed the men from the boys. They were hard on us. They were molding the team they wanted.”

Majors was “a great motivational speaker,” former defensive lineman Don Parrish said in an interview. “Some coaches will say the same thing over and over, but he would tell you something.”

Majors delegated a great deal of authority to his staff, particularly Sherrill.

“They were all incredibly fundamentally strong coaches, down to your feet,” Romano said. “ ‘What are you standing like a duck for?’ I believe that is the key to building a great team.”

In dealing with players, Majors was like the good cop and Sherrill the bad cop. Romano described Majors as “the knight in shining armor” with the “smooth, southern, velvety voice.” And Sherrill? “He was the piercing, look-through-you type.”

Said Dorsett, “You didn’t want to go see Jackie.”

Majors gave his players leeway off the field, but they had to earn it.

“We had fun, man,” Dorsett said. “We were rambunctious. He gave us some freedom. But once we got on the field it was all business. We worked hard and we played hard. But you had to work hard first.”

After spending most of two weeks in New Orleans without a curfew, Pitt beat Georgia, 27-3, in the Sugar Bowl to clinch the national championship. When it was 21-0, one press box wag reportedly said, “Well, I guess they’re drinking Bloody Marys down there now.”

John Terrill Majors was born in his grandmother’s house in Lynchburg on May 21, 1935, the oldest of six children, including five boys. His mother, whose first name was John but went by her middle name, Elizabeth, taught in elementary school. She was known as a friendly but outspoken woman, described by her son as a “fierce competitor.”

Majors’ father, Shirley Inman Majors, was an excellent all-around athlete in high school. He tried farming but changed his career path as a young adult, coaching football at three Tennessee high schools before moving to the University of the South in Sewanee, Tenn., as head coach. He stayed there 21 years and coached two unbeaten teams.

An outstanding athlete like his father, Johnny Majors started out at Lynchburg High School. In the last game of his freshman year, Lynchburg beat his father’s Huntland team, after which Shirley Majors declared that no son of his would ever beat him again. He then moved the family to Huntland. Three of John’s brothers also would play for Shirley Majors.

After rushing for 2,550 yards and averaging 17.7 yards per carry, the 145-pound Majors was highly recruited and chose Tennessee. A multi-threat, single-wing tailback, he excelled during his junior and senior years. As a senior in 1956, he led the Volunteers to a 10-0 record and finished second to Notre Dame’s Paul Hornung in the Heisman Trophy balloting.

In 1959, Majors married Mary Lynn Barnwell. She survives him, along with his son, John Ireland Majors, and daughter, Mary Elizabeth Majors.

Majors briefly played with Montreal in the Canadian Football League before turning to coaching. He was an assistant at Tennessee, Mississippi State and Arkansas (where he met Sherrill), before taking over at Iowa State in 1968. His teams there went 24-30-1 in five seasons, compared with 14-31-4 in the five previous seasons, and went to two bowl games.