Jiri Hrdina remains a passing acquaintance of Jaromir Jagr in their home country, now called Czechia.

As a scout with the Dallas Stars, Hrdina occasionally crosses paths with Jagr, still an active player in Czechia’s top hockey league, the Extraliga ledního hokeje (ELH or Czech Extraliga for those of the Anglo-Saxon persuasion).

Jagr also happens to be the owner of the team he plays on, the Kladno Knights. So playing and using his star power to draw ticket sales or sponsors is very much a business decision as it is a pursuit of happiness in the sport he still loves at the age of 52.

“As owner of the Kladno team, he’s very, very busy getting money from the sponsors to maintain the team, keep players happy,” Hrdina said by phone Thursday as he scouted a game in Czechia. “This season, it’s not really happening. They’re in last place of the (league), but he’s trying.”

That endeavor will take a temporary pause this weekend as Jagr returns to Pittsburgh, a place where he first encountered Hrdina as a teammate with the Penguins and became one of the most celebrated sporting figures in the history of the city.

Almost 23 years after he left the team through a messy divorce in July of 2001, Jagr will have his iconic No. 68 retired by the team prior to Sunday’s game against the Los Angeles Kings at PPG Paints Arena.

The 66-year-old Hrdina, who helped Jagr acclimate to life in North America, will be one of many of Jagr’s teammates from the franchise’s Stanley Cup championship squads in 1991 and 1992 on hand to celebrate the reunion.

So will Kevin Stevens, the hard-charging power forward of those dominant teams. Serving as a scout for the franchise today, he understands the significance of repairing the damaged relationship.

Related:

• Jaromir Jagr’s reunion with Penguins celebrated as ‘really important to this franchise’

• Mark Madden: From Kladno to Bayside, Jaromir Jagr put smiles on hockey fans’ faces

• Jaromir Jagr’s Penguins teammates recall when they realized they were playing with a legend-to-be

“It’s a great move for the organization,” Stevens said in November when the honor was announced. “He was always a Penguin. I know when anybody talked about Jaromir, they talk about what happened in Pittsburgh. It wasn’t about the (New York) Rangers or the (Boston) Bruins or wherever (else) he played. He’s always known as a Penguin.”

Of the 24 years he spent as an NHLer (and 34 in various levels of professional hockey), 11 took place across the street at the site of the Civic Arena.

And over that decade-plus, Jagr grew up as a human in a very public manner in front of a smitten fan base.

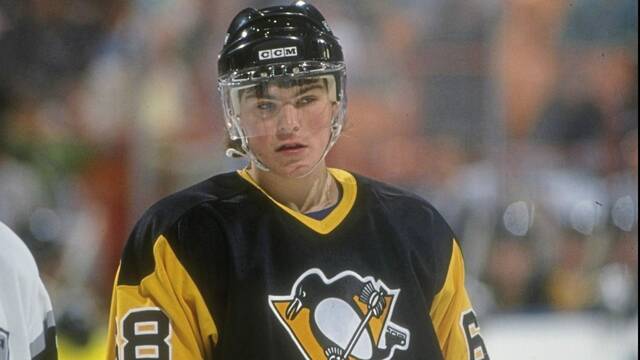

Arriving as a shy 18-year-old and departing as a demanding — some would say moody — 29-year-old, Jagr’s life as a member of the Penguins was captivating to fans, media and teammates alike.

Recently, a collection of Jagr’s teammates over those 11 years shared their memories of “Jags.”

Rough arrival

The Penguins drafted Jagr with the No. 5 overall selection in the NHL draft at a time when taking on players from Eastern Europe was an uncertain proposition.

The Velvet Revolution in late 1989 ushered out Communist rule in Czechoslovakia, the previous incarnation of Jagr’s homeland. The 1990 NHL draft in Vancouver took place roughly six months after the revolution.

After some quiet finagling by general manager Craig Patrick, the Penguins opted to take Jagr when other teams were still leery of selecting players from places not too far removed from Communist rule.

For Jagr, the adjustment was difficult. In addition to learning English, living in a country with freedom — a concept that was almost strictly a dream and far from a reality for him as a youth — was a welcomed but strange experience.

So was playing hockey in North America where the rinks are typically smaller than what is found in Europe.

Just over two months into Jagr’s rookie season, Patrick traded for Hrdina, a sturdy veteran bottom-six forward with the Calgary Flames.

“It was a time when I came to the NHL in Calgary and (Swedish forward) Hakan Loob was the only European on that team there,” Hrdina said. “He helped me the same way I was trying (with) Jaromir. After (several) months being on the team, just one Czech, he felt a little alone and kind of sad. I was just trying just to pump him up mentally, mainly.

“I think it helped when I came. He started to be feeling better. I explained things to him, explained things in English, translate some words, stuff like that. Then he became more comfortable. You would see that right away on the ice. He felt comfortable and started to play up to his potential.”

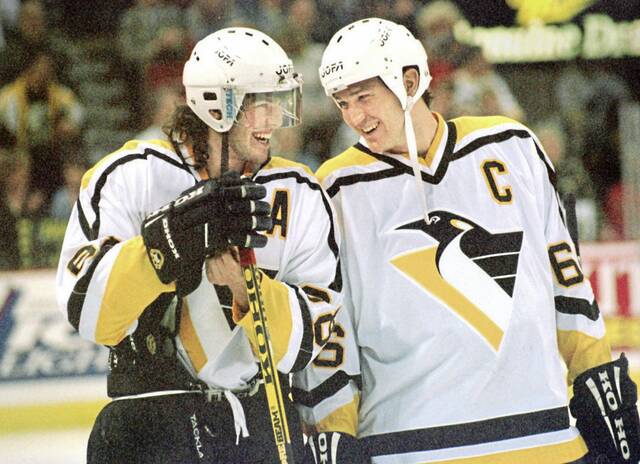

That potential ultimately was realized, especially early on as Jagr and Hrdina each helped the Penguins win the Stanley Cup in 1991 and 1992. But that success didn’t come without some obstacles.

“When he came to (the U.S.) after the revolution, there was still many, many things to adjust to,” Hrdina said. “The banking, the shops, whatever, it was totally different than what he had in Czechoslovakia at that time. Also, he was 18 years old. You forget that. He was just (a) kid. Coming to the league, it’s a pretty tough league.”

The presence of Hrdina, nicknamed “George,” was appreciated by teammates who were limited in their communications with Jagr.

“‘George’ was spectacular with him,” former forward Bryan Trottier said. “He was patient. And it calmed (Jagr) right down. He was getting a little homesick and frustrated. (Coach Bob Johnson) was trying to explain things to him. Bob’s got hours and hours and hours of patience. But when ‘George’ came, you could see this kid hit another gear and just calm down. He’s got someone that he can talk to, someone from his country that he understands. ‘George’ was great. It was good for all of us because we’re all trying so hard to help Jaromir. Just the language thing, he was homesick. … George was just a huge asset for Jaromir.

“To take on that role with Jaromir in addition, it just really fit on ‘George’s’ personality and the human that he is.”

Getting tough

Grant Jennings was a strong representative ofthe toughness the NHL offered in the early 1990s.

A stout 6-foot-3, 210-pound defenseman from Saskatchewan, Jennings was the embodiment of rough physical play that was typical of the NHL at that time.

That’s one of the reasons Patrick orchestrated the seismic trade he made in March of 1991, acquiring Jennings, fellow defenseman Ulf Samuelsson and forward Ron Francis.

Jennings wasn’t impressed by Jagr at first.

“Being in Hartford there, Ronnie, Ulfie and me, we always liked playing against Pittsburgh because they were offensive and they couldn’t handle the way we played,” Jennings said. “When we got traded there, we all knew who Mario (Lemieux) was, but then they said, ‘This Jagr kid is going to be good.’ I was like, ‘What are you talking about? He’s horse (manure)!’

“But he was young. It was his rookie season. He hated playing against a team like Hartford. But once we got there and started practicing with him and seeing what he could do, it was pretty impressive. Then we got into the games, he wasn’t just a practice player, he was a game player. When we got to the playoffs, seeing a European player like that in the playoffs was impressive.”

For as celebrated as Jagr’s non-pareil skills are, his sheer power might have been his most prominent trait.

It was to Samuelsson, who played a violent style that made him a hero in Pittsburgh (and a villain in most other NHL locales).

“We loved competing in practice,” Samuelsson said. “Some guys didn’t care too much about it, but Jagr always loved a good competition. Sometimes, we would seek each other out, whether it was one-on-one in a battle low or two-on-two, whatever it was. The thing Jagr loved and was so good at, he could have the puck and if someone came at him, he was so strong so he could most of the time absorb that hit. Then if he had you on his back, that’s exactly what he wanted. Because he could do whatever he wanted almost with a guy sitting on his back. That’s how strong he was.

“The only chance, the way I played it, if you ran him so hard, then for a split second, he would lose balance and then you could sort of get even in that battle and have a good chance to get that puck. But if you just kind of went out to him normally, kind of closing the gap and hit him half-(speed), he would just laugh at you and eventually make you look really bad. If I didn’t get him in practice, I would just let him go. I would skate away and take another run at him. He would get something going or I would get the puck from him. But you could never be sitting on his back.”

Jennings’ entanglements with Jagr in practice were similar.

“He was very hard to defend against in front of the net,” Jennings said. “Or him driving to the net. You had to be strong to defend against that and a lot of guys weren’t. I could do it, but it took all I had to keep him away from the net.”

Working it out

Jagr was clearly blessed with natural gifts, but he supplemented his abilities with a fastidious approach to working out on and off the ice.

“I hung out with him at his house (after practice),” said former Penguins forward Matthew Barnaby, whose family lived out of town. “I’d go over to his house and his mom would cook us borscht or whatever she was cooking. And he’d take a nap. I’d watch TV or go out, whatever. Then he would wake up at 5 (p.m.) and jump on the bike.

“Where I’m going out having a few beers, here’s the best player in the league jumping on the bike and starting to work out. This is crazy. He has his regimen where he’d go home, he’d get his rest, he’d eat, then he’d get a workout in late. It was always different times at night. It could have been five o’clock at night, it could have been nine, it could have been 11. But he was always getting those workouts in.”

Jagr’s workouts weren’t just obsessive. They were also creative.

“He used to put those ankle weights on his stick, down on (low) on his stick and stickhandle with those on there,” former Penguins forward Stu Barnes said. “That was different. You had never seen anybody do that before. You’d see his forearms and his hands and his strength over his stick and his shot, obviously, there’s a reason for that. It’s his hard work and dedication.”

Jagr even looked for ways to strengthen his mental approach to the game.

“He always had something going,” former defenseman Brad Werenka said. “We were in the gym one time and he’s looking at colors. He said when you look at colors, it will make you stronger. So certain colors are going to make you stronger, certain colors are going to make you weaker.”

Jagr apparently looked at the right colors when it came to the leg press.

“We would always look for a different adventure, different games or something different to bet on,” Samuelsson said. “We were in the gym one day and we said, ‘OK, let’s have a (competition) here. Everyone puts in a certain amount of money and sees who can do the most leg presses.’ Jagr had all the weights on you could possibly fit. Then our big (strength and conditioning coach) John Welday sat on top of the (machine). He probably weighed in at 250 (pounds).

“I’m guessing there’s between probably 500 and 1,000 pounds on there and Jagr starts doing these exercises like it’s nothing. He won that competition for sure.”

Jagr’s dedication often kept teammates on the ice well beyond the bounds of formal practice sessions.

“I was a backup goalie,” Ken Wregget said. “I would be spending an hour and a half after practice. I would do it myself because I knew if I had a chance to play against one of the top (players) in the world, it would make me a better goaltender and it also provided a backstop for him to help him hone his skills.”

Jennings, a left-handed defenseman, often faced Jagr, a right winger in practice.

“He’d always stay after practice, shoot pucks,” said Jennings, six years older than Jagr. “He’d always want to work on his game. Something that I should have done. He’d say, ‘Grant, you stay with me and work in the corners with me.’ I was like his toughest opponent on his team. I’d say, “No, I think I’m going to go for lunch with the guys and drink beer and eat chicken wings.’ But he would stay and work out all the time after practice and after the games.

“That’s why he’s still playing and why I’m limping around like an old man.”

Jokes like Jagr

While Jagr took the business of being in shape seriously, he never took himself too seriously.

He was, by many accounts, a good teammate. But not necessarily a nice teammate.

“It always seemed like he was always laughing,” said Barnaby, himself an agitator during his NHL career. “You don’t see that, especially from star players. They’re a lot more reserved than he was. He was always joking around, always making fun, always making fun of me.

“I was in the shower. He said, ‘I feel sorry for your wife that she has to have that come home to her.’ When I would walk by naked in the (locker room), he’d start making chicken sounds because I have small legs and he’d start calling me the chicken. Those are the things that stand out to me because those are the things you miss.”

Jagr challenged his teammates, mostly in good fun.

“We started arm wrestling then we get into a (normal) wrestling match,” said Werenka, a sturdy 6-foot-1, 221-pound defensive presence. “Ron Francis was on the bike there, he called a timeout. He calls me over, he goes ‘Wrenks, if you hurt him, then they’re going to ravage your house, all the fans in Pittsburgh. They’ll burn your house down then you’re going to get sent to Siberia.

“‘Don’t. Wrestle. With. Jags.’”

Jagr could instill fear in teammates as well.

“I had him pick me up from practice one day to take me downtown,” Jennings said. “I was living across from South Hills (Village) in a condo. He picks me up in his IROC. We’re going down (Route) 51 toward the city and he’s just speeding. I’m looking at him and I finally yelled at him, ‘Slow the (expletive) down!’ He goes, ‘No, no Jenner. It’s OK. I get a speeding ticket, I pay it.’

“I go, ‘No, that’s now how it works here. … If you get too many speeding tickets, you’re going to lose your license.’ He just kept speeding all the way into town. I was just staring at him like, ‘Where did you learn to drive?’ I was scared for my safety. I said, ‘We’re not going to the hospital. We’re just going to practice.’”

That carefree approach was seemingly Jagr’s default setting.

“He watched a lot of MTV,” Trottier said. “As his roommate (on the road), I watched MTV. That’s where he learned all of his English. It was kind of fun because if he got asked a question by one of the reporters, he would just answer with a phrase from one of the songs like ‘I like Cherry Pie.’ That’s (the band) Warrant. He liked the loud music.

“It was kind of fun to be around that youth, that enthusiasm, that desire. Obviously, it was refreshing for me because we built a good trust.”

Jagr’s affability didn’t exactly mesh well with all coaches, particularly a disciplinarian like Kevin Constantine, who took over the club in 1997.

But Jagr didn’t always bear the brunt of Constantine’s displeasure for his antics.

“At the start of practice, ‘Jags’ comes up to me, he goes, ‘Hey, can I have your stick?’” Werenka said. “I’m thinking, I’m not going to give him my stick. And he gives me his stick. Then he throws my stick over the glass. … I go to the bench to get my other stick because practice is about to start and he already took my (extra) stick.

“So, Constantine has to start practice right on time. … He was pretty strict with his rules and stuff and so I had to start practice with Jagr’s stick. My stick was a little shorter and Jags was always giving me a hard time because he said I had the worst stick in the league. … I had Jagr’s stick for all practice. A long stick because it was a foot and a half longer than the one I used. I knew that I was going to get in big trouble because I had only been in the league for about a year. I went through all practice with Jagr’s stick. I never missed a pass all practice. Then at the end of practice, Jagr is leaving the ice and Constantine comes over and just rips me. Just gives me, ‘You’re making a mockery of it. This isn’t a joke!’

“’Jags’ got me in trouble.”

Lifting others

Barnes was the fourth overall pick of the 1989 NHL draft by the Winnipeg Jets. He lasted an impressive 16 seasons as a steady two-way forward and enjoyed considerable team success with the Florida Panthers, Buffalo Sabres and Dallas Stars.

He only spent parts of three seasons with the Penguins. But his lone full campaign in Pittsburgh (1997-98) was by far his most productive as he scored a career-best 65 points (30 goals, 35 assists) in 78 games.

He thinks he could have done better.

“We had injuries throughout the lineup,” Barnes said. “Ronnie and Jags needed someone to play left wing with them. I got lucky enough to be the guy that got put on that line to figure out how to play left wing with those two guys. I’ve told a lot of people that 30 (goals) is good and sounds good. But based on some of the setups that Jags gave me — empty net opportunities and things like that — I probably should have had a lot more than 30. But it was incredible. It was just a blast to go out every day and play with him and watch him and be a recipient of some of his unbelievable work.”

Jagr won the Art Ross Trophy as the league’s top scorer on five occasions. He might have won it more were it not for his occasional linemate, Lemieux, claimant of the trophy on six occasions.

But once Lemieux’s various maladies forced him into his first retirement, Jagr took over as the Penguins’ — and the NHL’s — most dazzling offensive force.

“When he was playing with Mario, he looked up to him and it gave him time to grow up and bloom,” Wregget said. “When Mario stepped aside, he was the guy that stepped in and said, ‘OK, it’s my turn and I now get to show the world what I’m made of.’ To have a one-two like that on a team is amazing, let alone having the surrounding cast that they did.

“Very, very fortunate for hockey fans in Pittsburgh getting to see Mario Lemieux and Jaromir Jagr at the same time.”

While Jagr was a vital component of the franchise’s first Stanley Cup titles, perhaps his finest moment came in the 1999 playoffs.

Facing the New Jersey Devils, the top seed in the Eastern Conference, in the opening round, the eighth-seeded Penguins lost Jagr to a groin injury in Game 1.

Jagr missed the next five games as the Penguins slipped to a 3-2 deficit in the series. By Game 6, he gutted through his injury and scored a game-tying goal late in regulation at 17:48 of the third period.

Then at 8:59 of overtime, he scored off a feed from forward Martin Straka to give the Penguins a valiant 3-2 win at the Civic Arena.

— EN Videos (@ENVideos19) February 16, 2024

Two nights later, the Penguins upset the Devils, 4-2, in Game 7 as Jagr recorded two assists.

It remains arguably the biggest upset in the history of the franchise.

“He really couldn’t practice that whole playoff run there,” Barnaby said. “And (New) Jersey was good. They were a really good team. He put us on his back. That power play, when he got it on that right side, that wrister was coming. In between the games, the rest and the recovery and the therapy just to be able to play the games, pretty remarkable. It’s one of the reasons he’s at the best of all time. It doesn’t happen by accident.”

Welcome back

Sunday’s ceremony will heal wounds that have lingered for more than two decades.

After leaving the Penguins, Jagr suited up for the Washington Capitals, Rangers, Philadelphia Flyers, Stars, Bruins, Devils, Panthers and Flames (to say nothing of his time playing in Russia or Czechia).

And just about every occasion he came back to either the Civic Arena or PPG Paints Arena, he was booed, particularly during his tenure with the rival Flyers, which came about after a brief flirtation in which he discussed potentially re-signing with the Penguins in 2011.

His reunion with the Penguins is profound to those who played with him.

“You have a quick flash of him skating or his body of work, the first thing you think of is Pittsburgh Penguins,” Barnes said. “I know he went on to play in other places throughout the league and even throughout the world. But any snapshot of him, I think the first thing you think of is the Pittsburgh Penguins and the city of Pittsburgh.”

Absence has made the heart grow fonder for Pittsburgh and the curious superstar who arrived as an 18-year-old in 1990 and then left under sour circumstances in 2001.

“He’s 52 now,” Hrdina said. “Of course he has matured. … He is different. You’re talking (more than) 30 years difference. He’s mature. He’s a man. He was a kid when I was there, and he’s a man now.”