Mike Lange, as he always did during his career as the voice of the Pittsburgh Penguins, captured it perfectly.

When goaltender Marc-Andre Fleury made his NHL debut Oct. 10, 2003, he got a standing ovation during a 3-0 loss to the Los Angeles Kings at the Mellon Arena.

That reaction came late in the contest after he poke-checked the puck away from Los Angeles Kings forward Esa Pirnes on a penalty shot attempt.

Lange detailed the moment in perfect fashion.

21 years ago tonight:pic.twitter.com/9K99GPv33L

— Seth Rorabaugh (@SethRorabaugh) October 10, 2024

“He’s found a home in the city of Pittsburgh,” Lange said, calling the game for the former Fox Sports Pittsburgh. “Marc-Andre Fleury. He’s the hero of the night, and they’re losing, two-nothing. No question about it! You can feel it. You can see it!”

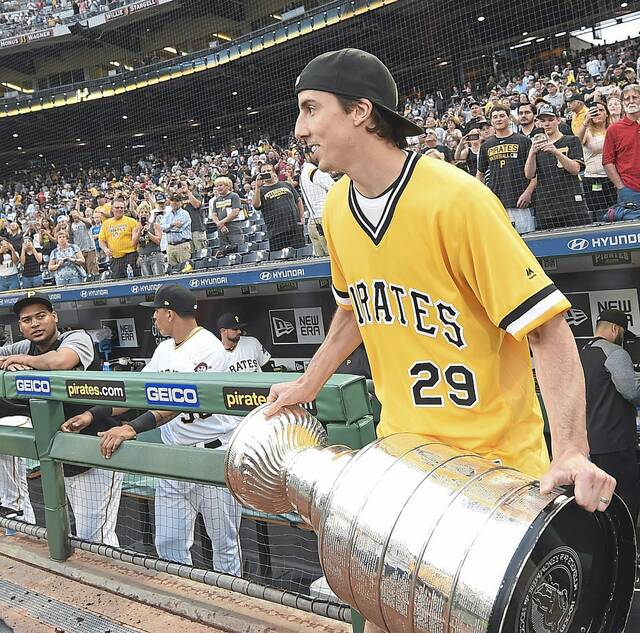

More than two decades later, Pittsburgh will get its presumed final chance to see the player who helped usher in the greatest era in franchise history.

On Tuesday, Fleury, now a member of the Minnesota Wild, is expected to suit up for what will presumably be his final game in the city he initially invigorated 21 years ago.

Fleury has indicated the 2024-25 campaign will be his last in the NHL, and barring a trade or a seemingly unlikely encounter between the Penguins and Wild in the Stanley Cup Final, he will not make any return visits as an active player.

A quick glimpse of Fleury’s base statistics will verify he is the greatest goaltender in franchise history. He holds most of the Penguins’ career marks including games (691), wins (375) and shutouts (44).

But those tabulations don’t offer a thorough enough explanation of what Fleury, the top overall pick in the 2003 NHL Draft, meant to a franchise he helped lead to three Stanley Cup championships (2009, 2016 and 2017).

Recently, a number of Fleury’s teammates in Pittsburgh offered what the “Flower” meant to them.

Early impressions

From the start of his time with the Penguins, Fleury’s affable nature, arguably his most prominent trait, was apparent.

As a rookie in 2003-04, he wasn’t shy about having fun at the expense of established NHLers.

“His first year, he was roommates with (defenseman) Marc Bergevin,” former Penguins defenseman Dick Tarnstrom said. “He bought an electric (fake) book and put it on its side. He said, ‘Read this page.’ As soon as (Bergevin) touched it, there was an electric shock. He did that to a veteran guy. It was so funny. Eighteen years old, and he did that. That’s confidence.”

Given the Penguins’ financial constraints at that time, Fleury only played a few games in the NHL in 2003-04 and spent the bulk of the season at the junior level. And with the NHL’s lockout wiping out the entire 2004-05 season, he played that entire campaign in the American Hockey League with Wilkes-Barre/Scranton.

He wasn’t afraid to be himself as a 19-year-old.

“When we were still (with Wilkes-Barre/Scranton) … he came dressed as Catwoman one time to a team party,” said defenseman Rob Scuderi. “We had this room reserved (at a restaurant). It was a great costume. At a certain point, the reservation fades and the room becomes just general use. At one point, we had to tell him to take the mask off because he didn’t have a bad figure for Catwoman. At one point, we were like, ‘Hey, Marc, I think you’ve got to take the mask off. You’ve got some suitors lining up.’”

Leading the way

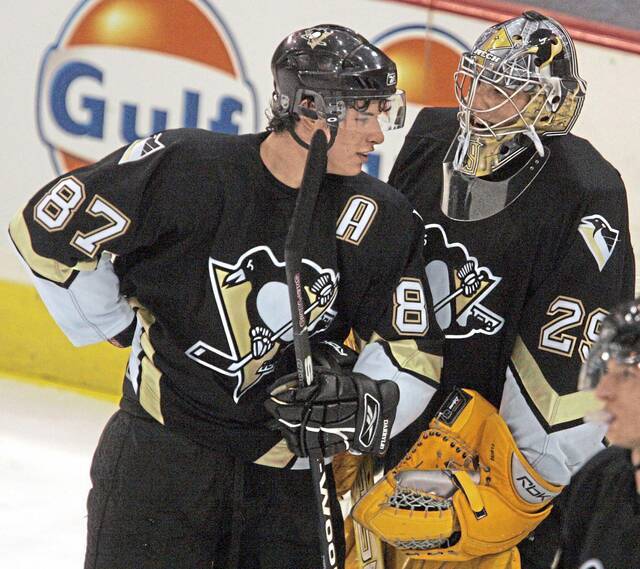

While much of the Penguins’ success over the past two decades is often affixed to star forwards Sidney Crosby and Evgeni Malkin and defenseman Kris Letang, Fleury was the first component of that foundation, arriving in Pittsburgh a handful of years before each of them.

As such, he took on the responsibility of welcoming them to their new surroundings while sharing a common level of expectations.

“It was huge,” said Crosby, the first overall pick in the 2005 NHL Draft. “I had met him before. We had played together (for Canada in IIHF World Junior Championship tournaments) and stuff like that. (Had) that relationship a little bit and just seeing how he handled everything — he had the pressure — but the way he handled it. He was a guy that loved coming to the rink. He worked really hard. He wanted to be the guy but in a really healthy way. … Really wanting that responsibility, being excited about the team and all the guys that were a part of it.

“That was huge when you come in and you feel that right away. That’s so important right off the start.”

Like Fleury, Letang (a third-round pick in 2005) is a native of Quebec. As a stranger in a strange land, Letang was guided by Fleury on and off the ice.

“Obviously, he helped me,” said Letang, a six-time All-Star. “There was a couple of training camps that I stayed at his house to learn how to be a pro and how to navigate unfamiliar waters. It was really helpful for me, especially as a young guy.”

Another Quebecois who was key in the rise of the Penguins during the 2000s was forward Max Talbot, an eighth-round pick in 2002. Talbot, who scored the Stanley Cup-clinching goal during the 2009 final against the Detroit Red Wings, had a particularly affectionate kinship with Fleury.

“I was always kind of close to him (before joining the Penguins),” Talbot said. “But when we got to (Pittsburgh) together, we did all those things, superstitious things before we got on the ice. It was always super fun because he approached it kind of the same way I did. We would prepare in a way where we were going to have fun playing hockey in practices and in games and (with) crazy stuff we would say to each other before we get on the ice.

“It was all about having fun and being grateful to be a hockey player. And having fun off the ice also by doing pranks and stupid stuff and laughing. We really hit it off and never looked back.”

Pranked

The stories of Fleury’s penchant for pranking teammates are well chronicled. He often bound gear together into a cocoon of tape or logged bubble gum into the deepest reaches of hockey gloves.

Perhaps his most notable prank was documented in 2010 on the HBO series “24/7” where he orchestrated the removal of all the furniture from the hotel room of forward Mark Letestu and Ben Lovejoy into a hallway.

“We never responded. We never did anything,” Lovejoy said. “You want to stay out of that guy’s crosshairs. You will never win when you go against Marc-Andre Fleury.”

Fleury’s commitment to pranks was thorough.

“Team dinners, he would go back for a pregame meal and sit underneath the table just to shoe-check someone (putting food on their shoes) for 45 minutes,” defenseman Deryk Engelland said. “He would stay under there until everyone left so no one busted him. The pranks he pulled, he would go all in for it. Everyone would figure it was him, but no one could prove it was him because he was so dedicated to pulling off his pranks without anyone knowing.”

Automobiles were often the focus of pranks.

“With (defenseman) Jay McKee, he had (a) nice Jeep and he would come to Mellon Arena all the time with it,” Talbot said. “One day, (Fleury) filled up his Jeep with popcorn through the roof. That was one of the best things ever, having a small jeep with the (top) open and was full of popcorn.”

That was a pattern that originated in Northeast Pennsylvania.

“I can’t remember whose car he did it to, but the old Wilkes-Barre parking lot was this massive, massive lot,” Scuderi said. “He took a guy’s car to the far end of the lot. … It had to be a half-mile walk at least to find your car in the lot.”

Attire could capture Fleury’s attention as well. When defenseman Justin Schultz arrived via trade in 2016, he quickly found his clothing suspended from the ceiling of what was then Consol Energy Center.

“Whenever he got (Schultz) with his clothes (during) his first practice with us, I remember (Schultz) is looking up,” Crosby said. “I don’t think (Schultz) actually realized they were his clothes. Honestly, the amount of stuff that ‘Flower’ has done, it’s not proven. All the stuff that he’s been involved in, you can’t actually prove that it’s him. That’s the best part about it is he’s been doing stuff for so many years, they still haven’t actually been able to verify that he’s the culprit.”

Fleury’s pranks weren’t limited to teammates. Or to mundane moments.

“The day of Game 7 when we won the (Stanley) Cup (in 2009), we were at the MGM (casino resort hotel in Detroit) that (day),” Talbot said. “And the afternoon of the game, there was a lot of noise around his room. The room beside him was making a lot of noise because it was a casino. … I remember him coming to the game laughing in the bus going on the way to the rink, for Game 7, the most important game of our lives. Marc was laughing because before he left, when he woke up from his pregame nap in the afternoon, he actually filled up a (small) garbage can full of water. He leaned it on the (noisy) room and knocked.

“So when the people opened the door, their feet were all wet. You think about it, it’s Game 7 and the starting goalie is doing pranks right before going in that game. It’s a pretty important aspect of his life, pranking people.”

Teamwork

While Fleury was not always a nice teammate, he was by all accounts the ultimate teammate.

In the early 2010s, the Penguins, under coach Dan Bylsma, held shootout competitions after seemingly every practice. At the end of a month, those competitions were labeled as “Mustache Boy” as the loser — the player who was last to score — would have to sport a mustache for the next month.

“‘Mustache Boy,’ I’m sure would have been really fun had I been a shootout guy,” Lovejoy said. “‘Mustache Boy’ was super stressful for a couple of guys that had no chance of ever taking a shootout in their life. Every month, there would be a couple of us just so nervous. It would ruin our practice. It was not something that I was good at. It’s not something the Penguins or Dan Bylsma would ever need me to do. But that didn’t matter. We did it anyway.

“We would go down and take our shot, make our move and very rarely would any of us have a chance at scoring. Marc-Andre knew this, knew how stressed we were and he took care of his defensive defensemen. As it got down to crunch time, he would go down for his diving poke check and he’d end up in the corner and let us gracefully bow out without a mustache for the month. At the time, he was one of the very, very best shootout goaltenders in the game.

“He was incredible. He was the best. We knew once we got to the shootout, we had a super advantage because we had Marc-Andre Fleury. And he took care of his defensive defensemen because he appreciated what we did in front of him. It was always things like that with Marc. This guy is a superstar, and he was always noticing what the fifth, sixth, seventh defenseman was doing and how he could make my life easier and my life better.”

Other shootout competitions with lesser stakes were labeled “Juice Boy.” The losers of those events would have to get drinks for teammates or wear silly clothing.

“We did these ‘Juice Boy’ (competitions), and I would always get anxious,” forward Joe Vitale said. “There was always a punishment for the person that scored last. I would get so worked up. The first couple of weeks, I struggled and I’d lose one. ‘Flower,’ he was very observant. He recognized that certain players were good at certain things and not good at other things. He appreciated that I put my body on the line every night for him and blocked as many shots as I could, won as many faceoffs in the (defensive) zone. It was more his way of thanking me. … He would always keep his legs really spread wide and he would point with his stick five-hole. I’d come down, and I’d rip one five hole. He would wave up his arms and (yell) ‘Ahhhhh!!!’ I don’t think I ever lost a ‘Juice Boy’ after the first three weeks because it was really him.

“Whenever I needed to score and I needed to get out of the (competition), I could always count on ‘Flower’ because he knew I lacked a lot of skill. He would just always help me out.”

Fleury would often resort to cheeky hijinks during those shootout competitions such as doing push-ups or covering his face as a shooter approached.

“You’re like, ‘This son of a (gun)’ and you’d shoot the puck and he’d jump up, catches it,” forward Mike Rupp said. “Or he’d put his glove in front of his face then all of a sudden you’d shoot it and he makes a save. It was frustrating.

“I said to him one day, ‘Hey Flower, honestly you should do that in shootouts (during games) sometimes. I tell you what, as a player coming down to shoot on you, even though I know you’re going to do it, it makes me so mad I just shoot.’ It’s like you internally combust. You just try to shoot it real quick.

“Weeks later, we’re going to a shootout. The (Zamboni drivers) are doing the dry scrape. ‘Flower’ comes over to the bench to grab a water and he says to me, ‘I’m going to do it.’ I’m like, you’re going to do what? He put his two hands in front of his chest and he makes a push-up (motion). I go, ‘No, no, no! Dude don’t do it! I was just messing with you.” He goes, ‘I’m going to do it!’ … I was like, if he does it, it’s either going to ruin him or it’s going to be legendary stuff. He went in his net, he was just looking over smiling the whole time. He never did it. I was so nervous.”

In addition to being a radio broadcaster in his hometown with the St. Louis Blues, Vitale coaches youth hockey in the area.

One lesson he passes along came from Fleury during his first steps into the NHL.

“I’m a rookie with (forwards) Dustin Jeffrey and Eric Tangradi — and at the end practice, we’re hanging around,” Vitale said. “The rookies, we can’t get off until Sid gets off because we can’t pick up pucks until everyone is done. We’re down in the corner and just like ‘Oh my god, Sid and (Fleury) will not get off the ice.’ They’re constantly playing and constantly working on things and having fun. Finally, practice is over and we go down on one knee to finally pick up pucks. We’re exhausted. I still have these images of ‘Flower ‘sliding in and getting on one knee to help us pick up pucks.

“I’ll tell my youth players now … I always tell the story, if Marc-Andre Fleury, if he doesn’t have a big enough ego to reach down and pick up pucks, everyone should pick up pucks. If ‘Flower’ can get on one knee and help rookies pick up pucks, everyone’s picking up pucks. So we have this thing now where the entire team picks up pucks.”

Still serious

Fleury’s affability largely masks the devotion he has to his craft. While he is blessed with hiccup-quick reflexes, he supplements those natural gifts with a determination to improve his play.

“We’d have practice where we’re doing a drill and it’s a continuous drill,” Vitale said. “It’s shot after shot. I remember vividly coming down. … I pick my head up and he’s still battling with the shot before me. If you watch him practice, he would accept that shot and if there was a rebound, he would stay with that rebound. If there was five rebounds, he would stay with that player until that puck was done. He didn’t care if he missed the next two or three shooters.

“You look at the way he competed in games is because he put in the work at practice. He did that better than any goalie I was ever around. Most goalies now, they accepted a shot, maybe one rebound then they dust it off and get ready for the next one. He would stay with it. Then if you look at him in games, the way he made that first save, second save, third save, fourth save. … He did it every day in practice. Even a warm-up drill. He would stay with that shooter.”

During his career with the Penguins, Fleury encountered a handful of inflection points that in some way altered his trajectory.

The first came during the 2007-08 season when he suffered a high-ankle sprain that cost him 27 games.

“He was hurt for a while, and I thought when he came back, he was just a little bit different,” Scuderi said. “He never lost the joy and the energy that he brought to the room. But I thought his mentality changed a little bit. Maybe being out and having to watch it, whatever happened, I thought he was a little bit different. We went on to the (Stanley Cup Final) that year and won the next year. It’s not shocking that he’s gone on to play 20 years because when your mentality meets your ability — especially for someone with the ability that he had — the sky is the limit.”

Another crossroads came in 2012 when he was diced up in a first-round playoff series loss to the Philadelphia Flyers. That carried over to the 2013 postseason when he was replaced by Tomas Vokoun as the starting goaltender. Mike Bales was hired as the goaltending coach and helped Fleury regain his All-Star form.

“If you recall, there was that stretch probably around (2013) where things weren’t going good for him,” Rupp said. “From talking to people, I think he changed and tweaked some things. He’s always Marc-Andre Fleury. He’s always going to smile. But I think the approach was a little bit different. It helped him.”

Perhaps his most difficult moment with the Penguins came when they let him go to the Vegas Golden Knights in the 2017 expansion draft.

With Matt Murray supplanting him as the Penguins’ top goaltender, Fleury went off to the desert and helped steer that franchise to a Stanley Cup Final appearance in its first season.

“At first, it was a little unsure,” said Engelland, also a charter member of the Golden Knights. “But as he got in here in the city and (saw) his welcome at the expansion draft (with) the cheers and stuff, that lightened the load a little bit. I don’t think anyone expected us to win so many games.

“Without him, we wouldn’t have had the year we had.”

Well spoken

While he has a very soft voice, Fleury was no shrinking violet when it comes to being chatty.

“He was always talking,” Vitale said. “He was always making noise. He was having a full-blown conversation (with) us on the ice. I’ll never forget blocking a shot and going down right in front of him. He would say ‘thank you’ to me while the game was still happening.

“(Another game), it was like a backdoor tap-in and I slid and I make a ‘save.’ The puck is in the crease, and I clear it with my glove. He tapped me on the head (saying) ‘Oh, thank you Joey V. ThankYou.ThankYouThankYouSoMuch. GetUpGetUpGetUp!’’

“I do remember a ton of times of him just having a full-blown conversation. This wasn’t in between whistles. This was during the play.”

There was plenty of talk before games as well. In particular, Fleury and Talbot had a well-known pregame routine where they knelt down next to each other in the runway from the dressing room, got face-to-face and bantered with one another.

“It was nothing planned at the start but it kind of probably worked one day where he had a good game, I had a good game and it became a ritual,” Talbot said. “I can’t really say what we were saying, but I can say it was not super serious. It was not like, ‘Hey, let’s go tonight!’ It was mostly talking about stuff that wasn’t concerned with hockey and trying to get loose in some way. I think it was gratitude also. That was always part of it. ‘Oh my God! We’re playing on (Quebec broadcaster) RDS tonight! Let’s go! Let’s play well against the (Canadiens). We’re so lucky to be here.’ It was also some funny (stuff) through all this.

“It was always special and always something different.”

Always fun

At 39, Fleury barely has any detectable gray hairs or wrinkles, and that is despite playing what might be the most stressful position in all of sports.

His carefree nature is his default mode.

“I remember doing (batting practice) at PNC Park,” Rupp said. “A lot of hockey players I feel like don’t play other sports. I don’t know if ‘Flower’ did or not, but it didn’t look like he played baseball. We’re taking (batting practice) and we’re taking some rips. Guys are hitting the ball hard. ‘Flower’ is standing at second base. Everybody else is shagging balls in the outfield. He’s standing in the infield. The balls are coming hot. He’s standing backwards with his back to the plate looking to the guys in the outfield. Balls are zipping by. He’s doing cartwheels. I’m like, ‘Dude, you’re going to get killed. What are you doing?’

“He just had no worries, no worries in the world. It kept him young.”

He found ways to keep his peers young as well.

“It was always fun being with him,” Rupp said. “He was always energetic. He was a reminder always that we’re kids playing a game, even if we’re 30 years old.”

“He always found a way to bring joy to the game,” Scuderi said. “He’s one of those guys, you’re not ever sure if he had a bad day. Most likely, he did, just like everybody else. But he certainly always bounced back with a good attitude. For the position, it must have been a huge attribute. If there’s any position where you can get down on yourself, it would be goaltender. For him to learn from something but also turn the page at the same time, must have been a tremendous attribute for the position he played.”

Fleury’s bonhomie could be an asset to teammates.

“If it’s someone else having a bad day, you get around him and that bad day’s gone,” Engelland said. “He just brightened the room anytime he came in and made everything fun which it should be. When you’re having fun, you’re playing your best. He’s one of the best guys at that. He made it fun for everyone no matter what was going on.”

Fleury even spreads that fun outside the rink.

“In Montreal, in August before he leaves to Minnesota, for two weeks, he rents this ice and we shoot on him, a couple of ex-players and friends,” Talbot said. “He does that in public arenas. He practices for two hours on the ice. And there’s often like 40, 50 kids just waiting for him to get autographs. He just smiles and just goes through all of them every time. He stays there for an extra 30 minutes with his pads on and signs (for) every single kid that goes to see him.

“He’s really a special individual and I’m very proud to call him my friend.”

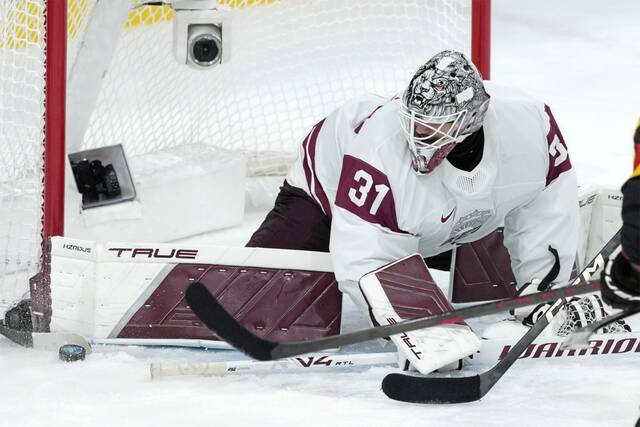

Full bloom

Fleury has been an outstanding goaltender by any measure and is bound to retire with the second-most goaltending wins in NHL history by the time his spellbinding career is complete.

(Through Saturday, he had 562 victories and would likely need another half-dozen seasons to catch up to Martin Brodeur’s 691 wins.)

His figures are spectacular and will ensure him a place in the Hockey Hall of Fame one day.

But the person, not the player, stands out more to his teammates.

“Whenever anyone retires, everyone talks about how great of a human being that person is,” Lovejoy said. “Marc-Andre is the greatest human being ever to play in the NHL. He is the absolute best person off and on the ice. Just a spectacular human. I was so lucky to be in the same orbit as him for a long time.”

That nature — and some outstanding natural talent — have allowed him to be an NHLer for 21 seasons.

“Marc, he was like a goofball,” Vitale said. “He was certainly dialed in but once the game was over, he was like a kid. He was a complete goofball, which I think really did help him because he found that balance where when the game was on, he was super intense. Then, he needed that flip side of being just his jolly old self when the game wasn’t on. That balance has certainly gifted him the career that he has.

“The fact that he’s been such a fun personality, he brings charisma everywhere he goes, he lifts spirits in every room that he walks into. That is just another thing on top of (his elite play). It’s that personality that has really gotten to the place he is at now.”

Fleury maintains a profound place in the memories of those he played with.

“It’s pretty easy to characterize Marc as probably the best teammate you’ve ever had,” Talbot said. “He comes to the rink with a big smile, works his (butt) off, stays in shape, always brings the right attitude to the rink. He also wants to win. He always wanted to be the guy. He cared deeply about being at the top. What he did throughout his career was pretty amazing.

“That’s pretty much what I think about ‘Flower’ as a hockey player but a human being also.”