His mates on the Braddock High School basketball team didn’t seem too interested, but Billy Knight was fascinated by the newest game in town. In 1967, the Pittsburgh Pipers were one of the charter members of the American Basketball Association, and Knight, whenever he could make his way to Civic Arena from Braddock, would watch games.

He remembers a friendly Arena employee letting him in so he could see this bold, new league that featured a red, white and blue ball, wide-open play and a shot worth three points.

The league was founded with the idea of eventually achieving a merger with the established NBA. Nine years after Knight first got an up-close look at the Pipers — and 50 years ago this month — the ABA opened what would be its final season before it merged with the NBA.

Well, it was a merger to those involved with the ABA. Many on the NBA side viewed it as an “expansion.”

Whatever the terminology, the ABA’s place in basketball history is undeniable. Sometimes chaotic, sometimes quirky but never boring, the ABA changed the game forever.

TribLive recently spoke with seven men who played during the ABA’s final season to get their thoughts on the league’s history and legacy.

THE LURE

To have any hope of getting itself on equal footing with the NBA, the ABA needed players. Good ones. Guaranteed contracts were the way to do it, and it swayed several players who otherwise might have gone to the NBA, even if they never saw a portion of the money they were promised by the frequently cash-strapped franchises. (When he was with the Virginia Squires, Dave Twardzik remembers the club having money problems. A teller at his bank in Virginia Beach — the mother of PGA Tour legend Curtis Strange — “bailed us out” when checks bounced. Swen Nater said he had a three-year contract for $45,000 a year “and twice as much as that, I never received.”)

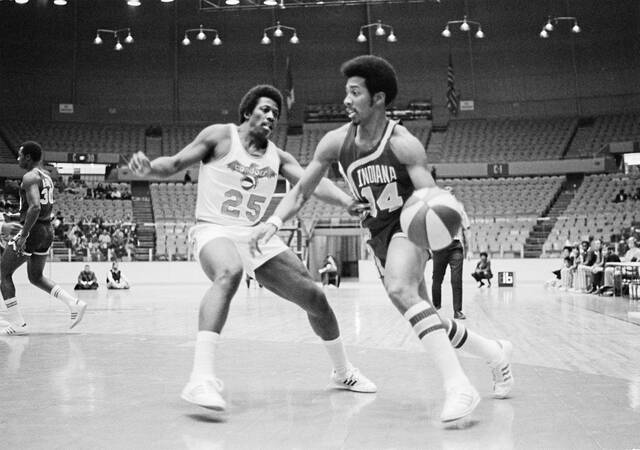

The ABA also offered opportunity for players to see action right away rather than potentially sitting behind seasoned NBA veterans. Besides, the ABA style just looked more fun.

Bobby Jones, forward, Denver Nuggets, 1974-76: “I went to the ABA because I felt like I could play fairly quickly there as opposed to being drafted by Houston (of the NBA). … As a rookie, all you think about is trying to survive and do your best.”

Swen Nater, center, Virginia Squires 1973 and ’76, San Antonio Spurs 1973-75, New York Nets 1975-76: “I got drafted (in the NBA) by Milwaukee, and they had a guy named Kareem Abdul-Jabbar over there. I didn’t want to go to Milwaukee and put him on the bench (laughs).”

Nater already had spent the bulk of his college career sitting behind Bill Walton at UCLA.

“It was a chance for me to finally play.”

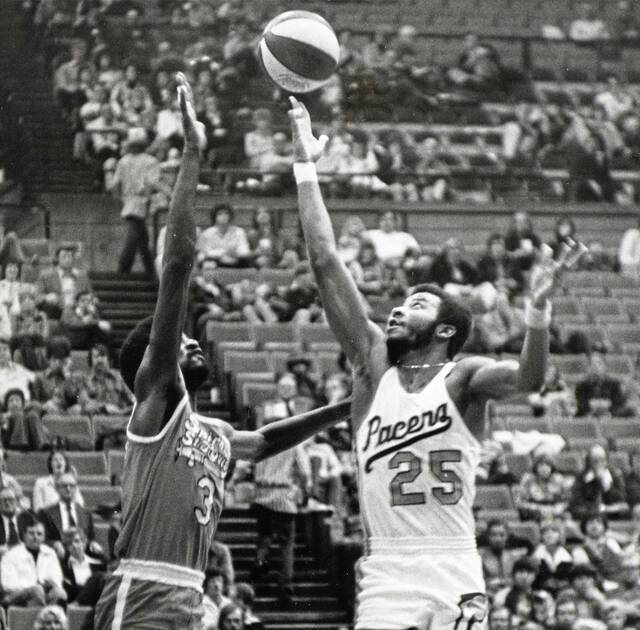

Freddie Lewis (McKeesport), guard, Indiana Pacers 1967-74, Memphis Sounds 1974, Spirits of St. Louis 1974-76: “We (the ABA) would run and shoot and dunk and (shoot) 3-pointers. Our game was a fast-paced game, where the NBA was a slow-down game, and we felt people wanted to see more dunks, more running up and down the floor and more 3-pointers.”

Len Elmore, forward/center, Indiana Pacers 1974-76: “I was looking for security and commitment. … I was offered a three-year contract, two years guaranteed, by the Washington Bullets (of the NBA). On the other hand, the Pacers offered me six years, all guaranteed, at a higher rate. When you look at the two deals, taking the Pacers deal was a no-brainer, recognizing that — or hoping that — the merger would occur, and I eventually would be playing in the NBA.”

Knight, Indiana Pacers 1974-76: “The Pacers offered me a five-year guaranteed contract. The Lakers offered me a two-year guaranteed contract. My mother didn’t raise no fool.”

THE BATTLE

From the time it started, the ABA was in a constant fight, not only for its own survival but against how it was portrayed in the media and by the NBA.

Jim Eakins, center, Oakland Oaks/Washington Caps/Virginia Squires 1968-74, Utah Stars 1974-75, Squires/New York Nets 1975-76: “During this time, NBA officials, especially people like (Boston Celtics owner) Red Auerbach and (New York Knicks coach) Red Holzman, those guys just kept referring to us as a bush league. ‘Those players over there (ABA), they can’t carry our players’ gym bags.’ We were fighting, all of us … being labeled like we were by the NBA and the press carrying those labels. Athletes are very proud people, and so there was not only pride in us and our individual games. There was pride in our teams. There was quite a bit of pride in the ABA.”

Dave Twardzik, guard, Virginia Squires 1972-76: “They thought the ABA was an absolute joke and everything was a gimmick: the red, white and blue ball, the 3-point shot, the style we played.”

Elmore: “We were treated like the stepchildren, literally. Media, everybody treated us like stepchildren on a national basis.”

Knight: “I had seen the ABA, obviously, with the Pipers being in (Pittsburgh), so I wasn’t an anti-ABA person. Some people were because the NBA was a great league. They had established themselves, they had sponsorships, they had the money, the TV contracts and all of that stuff. The ABA just didn’t have all of that.”

Nater had a strange feeling he didn’t do the ABA’s “stepchild” reputation any favors during his rookie season.

Nater: “I didn’t play but two, three minutes a game (at UCLA). And I got drafted (in the NBA first round) because the GM at Milwaukee, Wayne Embry, he knew I could play and he had seen me play. … But here’s the deal: Nobody really knew how good the ABA was compared to the NBA. … So here comes a backup center who becomes (ABA) rookie of the year … and that didn’t do the ABA any good at all. A backup center who was that good in the ABA? It wasn’t until I got to Milwaukee after the folding of the ABA that people saw that I was for real.”

THE TALENT

As the ABA forged ahead, despite franchises moving and folding, it began to accumulate a significant amount of talent. Many former ABA players point to the 1977 NBA All-Star Game, the first year after the merger, as proof. Julius “Dr. J” Erving, who had played exclusively in the ABA before the merger, was the game’s MVP, and 10 others who had played in the ABA were on the rosters, meaning 11 of the 24 NBA All-Stars that year had ABA roots.

The first NBA championship after the merger featured four starters who came from the ABA — Philadelphia’s Erving, George McGinnis and Caldwell Jones and Portland’s Maurice Lucas (Schenley) — plus Twardzik, who averaged 16 minutes and 6.7 points per game for Portland. There are 16 players with ties to the ABA in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.

Jones: “I remember we played an exhibition game against Boston in that last year, and we won … so, yeah, I felt like, the year after the leagues merged, if you look at the All-Star game the next year, there were quite a few — if not half of them — ABA players that were on that All-Star team. … I feel like when the leagues merged, there were some nights (in the NBA) where I was thinking, ‘This is going to be a night off.’ In the ABA, there was never a night off. I felt like there was always somebody that, if you didn’t work hard, they were going to score 20-30 points on you. ”

Eakins: “As the seasons went on, and the owners and teams got more and more serious about this ABA league and putting money into it and bring in talent — the David Thompsons, the Dan Issels, the Artis Gilmores and all the other great talent that upgraded the teams — if we played the top teams (from the NBA), and they won, at least they would know they had been in a hell of a game.”

Twardzik: “We certainly were an extremely talented league. … We just didn’t have the media exposure and the big-city markets that the NBA had wrapped up.”

Knight: We in the ABA felt that we had good players, too. There were quite a few of us in the All-Star Game after the leagues merged. … We were proud of the fact that there were so many ABA players.”

Nater: “After the (ABA) folded, they saw the quality. We had great players. We just didn’t have as many of them.”

THE DOCTOR

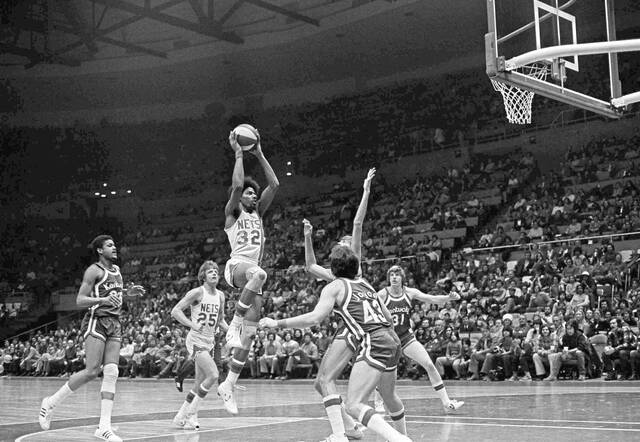

Erving was the unquestioned face of the ABA, and his unique talents made the NBA salivate. Erving, more than any other player, took advantage of the league’s fast, above-the-rim style.

Jones: “He was such a threat with his big hands. He controlled the ball really well in the air. Good shooter, clutch player and he played good defense. Savvy player. I can remember several times trying to front him in the low post and didn’t get much weak-side help then just getting dunked on.”

Nater: “When you have one superstar on a team, he can entertain. If there are more, then they can’t entertain as much. When Doc went to the 76ers, he did great things. But not like he did in the ABA where he always had the ball.”

Twardzik: “He was the guy who carried the torch for the league. There’s no doubt about it. … (In the ABA) he was younger, he was healthier, he wasn’t having any knee problems. … And what he did during games paled to what he did during practice. … And some of the stuff he did in practice was like, ‘Oh, my God!’ … My first year in the league … I can remember sitting on the bench and Doc would do something, and you lean (to the guy next to you) and go, ‘God, can you believe that?’ ”

Elmore: “He was what I would consider the queen on the chess board: could move and play any position and do anything. He was something to behold then, no question about it. He wasn’t constrained by the coaching notions of the NBA that were hard to shake, so to speak. There was a level of improvisation in some instances because of how the 3-point line affected the pro game. It stretched the floor, opened up driving lanes, gave guys better opportunity to create off the dribble particularly, as opposed to the NBA. … Julius could show the totality of his talents.”

Knight: “He was a big reason as to why they merged the leagues because he was a big name, and they wanted him in the NBA. … He was a name that was destined to be in the NBA.”

THE END

The 1975-76 ABA season — its ninth — opened in October with 10 teams. Just a few weeks later, the league was down to seven. The Baltimore Claws folded before playing a game. The San Diego Sails folded after 11 games, and the Utah Stars ceased operations after 16 games. The remaining teams pushed on through the chaos, hoping the rumored merger would come to fruition.

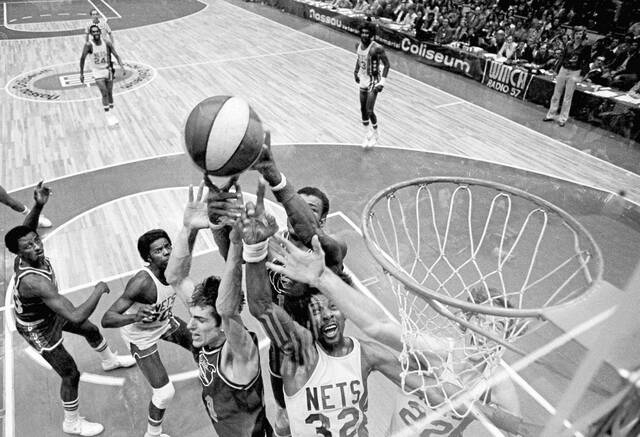

The Nets, led by Erving and Eakins, defeated Jones’ Nuggets in the finals.

Eakins: “While we were playing, no one knew this was going to be the last year. We were just playing for another championship, then we were going to have the offseason and everything would start up again. There was no inkling to the players, at least, that things were bad enough that this was going to be the last year.”

Twardzik: “I think the people invested in (a) franchise with the hopes of a merger that was going to be driven by a TV contract. The problem was small markets. You look at the teams that went into the NBA — other than (the Nets) being in the New York metropolitan area — you have Denver, small market. San Antonio, small market. Indiana, small market. The lifeblood was going to be the infusion of money from a TV contract, which never came. … When you see a team that’s financially struggling or is put up for sale, that definitely gets your attention whether you’re a player on that franchise or a team in the league.”

Lewis: “We kind of knew (the merger was coming). We felt like (the ABA) was a big success, and that’s what we really wanted to do.”

Elmore: “People had one eye on the economic and financial news as well as on the basketball news itself. We recognized that there were four franchises that were solvent enough that the NBA would want to incorporate.”

Knight: “Sure, we’d heard about it, that there could be a merger. But we were playing our season. … We didn’t know for sure that it was going to be the last ABA season. … In some ways, (franchises folding) could have been unsettling. We just rolled with it. You just played those teams that were left in the league. You just played them more often.”

THE AFTERMATH

After the 1975-76 ABA season, Indiana, Denver, San Antonio and New York were added to the NBA. Players from Virginia, St. Louis and Kentucky went into a dispersal draft.

The Silna brothers, who owned the St. Louis franchise, struck what might be the greatest deal in the history of sports. They negotiated for themselves a portion of the TV revenue from each of the four ABA teams that joined the NBA. And the deal would last in perpetuity. Thanks to the NBA’s skyrocketing TV contracts, the Silnas, by the 2010s, reportedly had made more than $300 million. In 2014, according to reports at the time, they reached a $500 million settlement with the NBA to end the deal. Reports estimate that the Silna brothers made more than $1 billion over the course of the deal.

The ABA changed the NBA. The 3-point shot became a weapon for many offenses. The Slam Dunk Contest, which originated at the ABA’s final All-Star Game, has become a staple of NBA All-Star Weekend. And the more open style of play paved the way for the “Showtime” Lakers, Celtics and Bulls dynasties — and those huge TV contracts — that would follow.

Jones: “It was a real innovative league. … And they kept (stats for) steals and blocked shots, and the NBA didn’t do that at the time. They were a little bit ahead of their time. I felt like it had a big influence in that era.”

Eakins: “I wholeheartedly feel the ABA was vindicated. … Definitely not to the point where we couldn’t carry (the NBA’s) gym bags. The ABA really changed the game. I would hope that people would give the ABA credit for changing the game. … So much of the NBA was staid. It was not an exciting game. It really wasn’t. … So we had the red, white and blue basketball, and we had an up-tempo style … and the 3-point shot. Dr. J then took it to the next level of playing above the rim. All of that changed the game, and people became excited about the game again.”

Twardzik: “There was a lot of talent. … Back when I played, teams weren’t taking 10, 15 3-pointers a game … now half their attempts are from the 3-point line. We revolutionized the game. When I was with Portland (after the merger), there were still a lot of teams that were playing old-style NBA. … The ABA wasn’t built that way. It was definitely built for entertainment.”

Lewis: “We had some of the greatest players of all time in our league, and when they came to the NBA, they made a statement. There was a lot of them inducted into the hall of fame, and a lot of them went to (NBA) teams, and they started on those teams.”

Nater: “We had guys like Dr. J, they were entertainers.”

Elmore: “I think it was the focus on entertainment, fun-and-gun type of mentality. The personalities that came out of the ABA, particularly some of the earlier personalities before I even got there … those personalities kind of made the NBA legendary. … The colorful nature of the league, and that’s not just the ball.”

And for that kid from Braddock who was there to see the league’s beginning and its end, he still takes immense pride in being a small part of the ABA’s legacy.

Knight: “It’s revolutionized basketball all over the world: the 3-point shot, the shorter shot clock and the wide open game that opened the game up for more individual talent being displayed. … It’s a fan’s game, too, so it’s got to be fun and exciting and enjoyable. … ABA people are very proud of the fact that they helped revolutionize basketball with some of the things that they invented.”