A dead body.

That’s how Duquesne basketball player Halil “Chabi” Barre described himself for the first 72 hours after the incident.

“The first two to three days, I felt terrible,” Barre said after practice Friday. “My body felt weak. I couldn’t even lift my arm. l was just laying down like a dead body.”

Ten months after his collapse in late January, though, Barre wants Dukes fans to think of him in a different way now that he is making his way back to the court for Monday night’s season opener against Cleveland State.

“When something you love is taken from you, it turns you into a lion,” Barre said.

Barre’s first season on The Bluff was cut short on Jan. 30. That’s when the 6-foot-9 forward from the western African country of Benin went up for a dunk during pre-practice warmups. Then, with no warning signs, he collapsed.

“It’s probably the most frightening thing I’ve ever seen as a coach,” Duquesne coach Keith Dambrot said during his SportsNet Pittsburgh coach’s show last week. “Especially when you’re sitting there looking at him and not really knowing what’s going to happen.”

As Duquesne associate athletic director of sports medicine and performance John Henderson recounts, within four minutes, the practice gym at the UPMC Cooper Fieldhouse was filled with campus police and emergency personnel responding to a 911 call from assistant coach Dru Joyce III. Athletic trainer Yuta Ozawa (now with the Sacramento Kings) had an AED (automated external defibrillator) hooked up to Barre within 30 seconds.

“When I look at what happened that day, other than an emergency room, I can’t think of a better place for him to be to get immediate, potentially life-saving care,” Henderson said.

Barre said it was about four or five hours before he was even cognizant of the fact that he was in a hospital. It was eight days before he was released.

From that point on, for Barre, it was an unending series of tests to find out what happened. He went to UPMC Mercy, UPMC Shadyside and Allegheny General Hospital.

A month after the incident, Barre underwent an electrophysiology study. Physicians entered the femoral artery in his thigh and snaked an electrode into the heart in an attempt to stimulate different spots and reproduce any possible arrhythmias. The test was negative. So Henderson described that as an encouraging sign that an arrhythmia was less likely to be the catalyst for the problem.

In June, Barre got a heart monitor implanted into his chest. Through an app, it constantly feeds data on Barre’s heart rate in real-time to his phone and to those that belong to the training staff as well.

Barre says he doesn’t like to look at the readings. He prefers to let the medical staff track that and follow their instructions.

“I can feel it (while) playing. It’s not hurting, but I can feel that something’s right next to my heart that’s moving. For a while, it was tough to get used to. But the doctors say don’t worry about it. It’s nothing. But I’m still trying to get used to it,” Barre admitted.

Throughout Barre’s comeback, anytime he was on the court at practice or running drills, a trainer had the app open and told Dambrot it was time to pull Barre any time his heart rate would hit a certain amount of beats per minute.

For a while, Barre said he would get tired quickly but would recover quickly. Barre steadily pushed his rate of practice upward as he was monitored.

“He was driving us crazy, to be quite honest,” Dambrot said. “He wanted to play from Day 1, really. He’s a guy that wasn’t going to take ‘no’ for an answer — whether it was here or somewhere else. He’s put a lot of time into this. He comes from a place where he didn’t have a lot, and basketball is very, very important to him. So I can’t blame him.”

To date, no exact cause of the incident or diagnosis of a specific condition has been given to Barre. So Henderson is reluctant to even officially call the incident a cardiac-related event. But, based in part on security camera video from the back gym at the UPMC Cooper Fieldhouse, that is the starting point from which Barre’s treatment began.

More sports

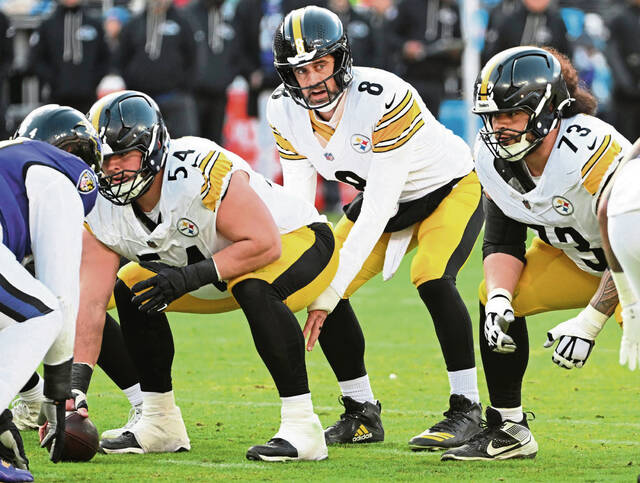

• Madden Monday: George Pickens is upset at Steelers' offense. 'In this case, Pickens is right'• Ke'Bryan Hayes becomes 1st Pirates 3B to win NL Gold Glove Award for defensive excellence

• Steelers’ Dylan Cook views self as future contributor at OT, not just an ex-NAIA QB

“Our physician thought it appeared to be cardiac collapse. We went through a multitude of tests, and we found out everything that it wasn’t,” Henderson said. “Whenever you have this situation, the student-athlete can go through a million tests. Our team of experts was no less than four doctors. Between what they found and what they didn’t find, they do what’s considered a risk stratification. What is your risk of sudden death? What is your risk of this event happening again?”

Last month, it was determined that Barre could be cleared for practice and play without restrictions.

“It used to be with this type of stuff, it was ‘You’re out.’ That’s not the case anymore,” Henderson said. “Shared decision-making is a common term in medicine now. That is applied to this scenario as well. And the decision-making is leaning on the advice of the medical experts. It involves the student-athlete what they want. It involves their family. And it involves the institution. And so the decision to return him to play involved quite a few people.”

Because this occurrence happened just a few weeks after the on-field collapse of Buffalo Bills defensive back Damar Hamlin, Barre wanted no part of the attention he was sure would follow. So he asked Duquesne to keep the matter quiet.

That’s what the school did, never attaching a reason for his absence from the team for the final two months. But the players did start wearing light blue hearts on their jerseys in his honor. When fans and students on campus made the connection and word of mouth spread, Barre said the support he received in private was significant.

“Since I’ve been out with my heart issue, every single game, they call my name from the stands,” Barre said. “They say, ‘We’re praying for you. Get well. Get back real soon.’”

Now, he wants to pay that back on the court starting Monday.

“I really believe in myself. I believe in stuff that I can do. And last year, I didn’t get a chance to show the fans what I can really do. Now, I feel like I’m more comfortable with the program and how Coach D wants to play. So I feel like I have to show the fans what they haven’t seen from me yet,” Barre explained.

Based on the scare Barre endured over the winter, just being out there should be reward enough for the fans who supported him.

But the “lion” within him wants more.