The Westmoreland Symphony is tuning up for the new season, including hiring a handful of new string players, to open with a splash by performing three of the most popular Russian composers.

“For me, Russian music is among the most colorful, most dramatic and the most challenging of all the repertoire,” says the orchestra’s music director, Daniel Meyer. “I love to get the orchestra stretched but also playing music that makes them sound really good at the start of the season.”

Meyer will conduct the Westmoreland Symphony Orchestra in “Russian Masters” to open the ensemble’s 51st season Oct. 12 at The Palace Theatre in Greensburg. The program is Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s “Polonaise” from his opera “Eugene Onegin,” Sergei Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto No. 2 with Alexi Kenney as soloist, and Dmitri Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5.

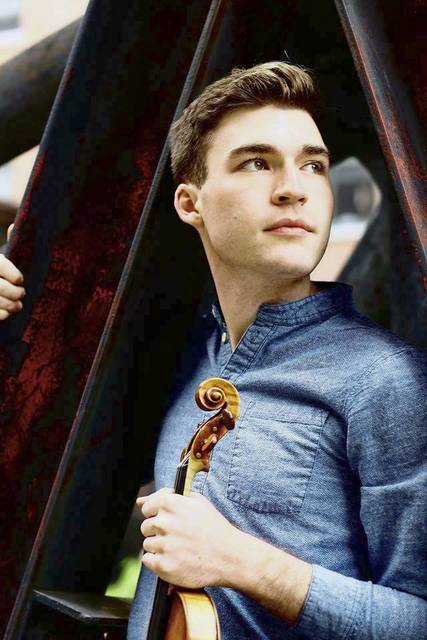

The more popular of Prokofiev’s violin concertos was one of the first parts of the program Meyer decided upon, in part because he is eager to collaborate with Kenney. The young American violinist is active as a soloist and chamber music enthusiast. He won a 2016 Avery Fisher Career Grant and is a frequent guest concertmaster with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra.

“He has that wonderful combination of brilliant technique and also bristling and bubbling energy I thought would be perfect for this piece,” the conductor says. “That’s just how he lives his life. He exudes that spirit.”

Prokofiev wrote his Second Violin Concerto in 1935 for a French violinist, shortly before the composer resettled in his native land after nearly two decades in the West. It opens with a hauntingly lyrical solo for unaccompanied violin, and includes a wonderfully singing slow movement and exciting, Spanish-tinged finale, which includes castanets. The world premiere was in Madrid.

‘An attempt to save his life’

The Shostakovich Fifth Symphony was written only two years after Prokofiev’s violin concerto but occupies an entirely different psychological realm. Meyer says he wrote it as “an attempt to save his life,” and the composer’s life at the time was harrowing. He had been denounced by name and harshly as “an enemy of the people” in Pravda at a time when millions were being killed in dictator Joseph Stalin’s purges. Shostakovich later wrote that the fear he felt that the KGB would come for him in the middle of the night never left him.

“There’s a degree of desperation built into this piece that’s palpable and makes it even more interesting. For me, Stalin cast a shadow over the whole piece, especially the finale,” Meyer says.

Yet Shostakovich was so skilled a composer that his music could also sound like a heroic affirmation of the human spirit, more in line with the aesthetic tone Soviet authorities wanted. It’s didn’t hurt the composer’s attempt to survive when a critic called the symphony “a Soviet artist’s reply to just criticism.”

Both Prokofiev and Shostakovich were harshly attacked in state media in 1948. Prokofiev died on the same day as Stalin, March 5, 1953. But Shostakovich lived to drink in celebration of the tyrant’s death.