Story by MEGAN TROTTER, DINARI CLACKS, HALEY MORELAND

Photos by SHANE DUNLAP

TribLive

Sept. 8, 2024

The breakneck pace of advancements in artificial intelligence development has led to the technology touching seemingly every facet of life, from work to finances to health care.

That rapid growth and unchecked development have created as much anxiety as hope, from Wall Street to the White House.

But while AI is becoming ubiquitous, it isn’t going to replace the human brain anytime soon, according to most experts.

Still, experts caution, the technology has drawbacks — dangers that humans must recognize if it is to be used to its fullest.

AI is an umbrella term that covers a wide variety of technologies, from the tech involved in autonomous vehicles to virtual assistants such as Alexa and Siri to text generation tools such as ChatGPT. Even AI industry experts seem to disagree on exactly how many “types” of AI there are.

In simple terms, AI uses algorithms — large, complex programs — that tap into gigantic data sets, sometimes the whole of the internet, to make predictions. Those predictions can make it seem as though the computer is “thinking.”

Sunday

• Who are the founding fathers of AI? / What are the different kinds of AI?

Monday

• How AI is being used for finance and investing

Tuesday

• AI technologies are giving some doctors more time for patients, improving health care

Wednesday

• AI in the news; how it impacts what you read

But AI can’t “think” the way humans do, said Chris Forester, an associate English professor at Syracuse University whose focus is digital technologies, like AI, and how they can be applied to various aspects of human life.

Tom Mitchell, who founded Carnegie Mellon’s Department of Machine Learning in 2006, gave a simple example: You could show a computer program photos of your mother and then photos of people who are not your mother. With the gained experience, the program would be able to identify the features that distinguish who is a positive example of your mother and who is not.

Forester agreed, saying it’s a mistake to assume AI can think like humans or that AI technologies are doing something supernatural.

“The word I hate the most … is it’s ‘magic’ because no one totally understands exactly how it’s working,” he said.

What AI really is doing, experts said, is logging hits and misses, correct answers and incorrect answers, by using as much data as it can find. It can remember the right answers, usually, and provide answers to questions, write reports and streamline data processing.

It does the same thing to create images or even videos that didn’t exist in real life.

This gained experience can lead to increased efficiency, from highly involved tasks such as poring over data in a spreadsheet to something as simple as the next text you send.

The possibilities seem endless.

And make no mistake, practically everyone is using AI or affected by it.

A search engine that suggests the rest of your inquiry? That’s AI.

Your smartphone suggesting the next words in your text or email? Also AI.

You even see AI’s shortcomings on a daily basis.

Remember that word autocorrect changed in your company-wide email or text message that embarrassed you? That was AI getting it wrong. That’s because not all of the information AI collects is correct.

Much of the conversation about AI revolves around how it is affecting, or will affect, the workplace.

“I think it is going to change a lot of things. I think it will change what employment looks like, what kind of jobs exist and don’t exist, what kind of jobs disappear and what kind of new jobs appear,” Mitchell said.

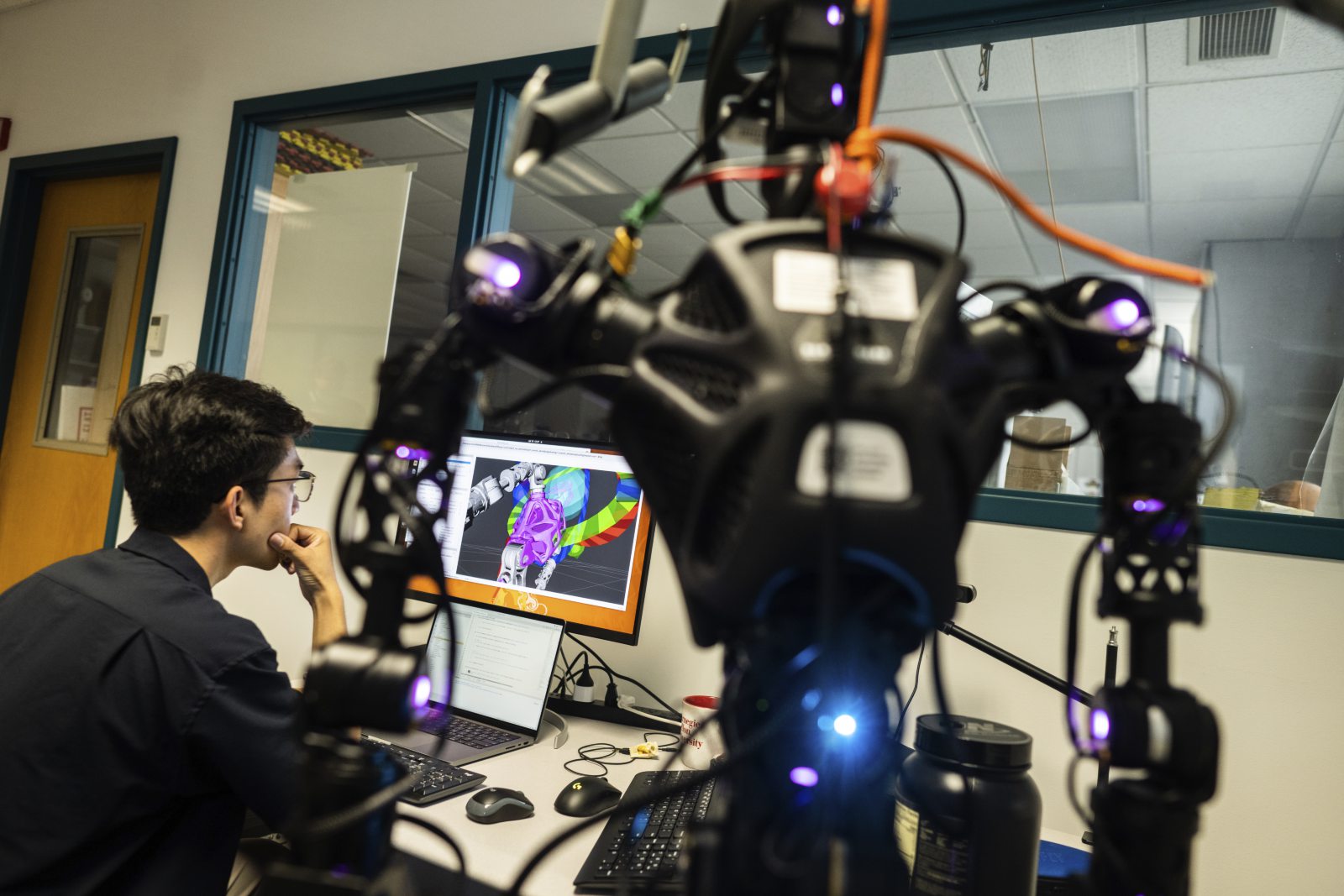

The focus of CMU’s Machine Learning Department is to build computer programs that improve their skill at a task through experience. The experience comes from trolling through mountains of data available on the internet.

Machine learning has led to the development of newer technology such as ChatGPT, launched in 2022. ChatGPT takes large amounts of model language information, the words, syntax and grammar that makes up a language, and uses it to understand conversation, analyze text and language flow, and predict future text.

ChatGPT has various levels, but even the publicly available, free version can — within seconds — compose simple stories and complete other tasks in response to inquiries typed into the program.

Such technologies require a lot of information, Forester said.

“What we’re talking about is almost always collecting, in many cases, just gobsmackingly large training datasets and carefully curating some task like, ‘make this noise look more like an image’ or ‘predict what word is going to come next,’ and that is the thing that we sort of grouped together and call AI,” Forester said.

Companies have spent trillions of dollars ensuring that datasets used to create machine learning programs are filled with reliable information. Sometimes, though, those datasets can reflect the less-desirable aspects of human nature.

“Civilization has been shaped by patriarchy, or colonialism, or anti-Blackness or white supremacy — those forces have shaped the record over 200 years,” Forester said. “These very sophisticated ‘AI systems’ require enormous amounts of data. That means oftentimes scooping up absolutely everything you can, but ‘everything you can’ often means data that has bias built in.”

Forester calls this phenomenon “algorithmic bias.” Algorithmic bias is just one reason people mistrust AI — and a reminder that these technologies are still in their infancy.

“People on both sides who are like, ‘this is the beginning of the absolute end’ are usually proven wrong,” Forester said. “And people who believe, ‘this is going to solve everything once and for all. We’ve finally done it,’ they’re usually wrong.”

Forester said he believes AI will integrate into society just like email did.

“It’s interesting to see the sorts of things that it’s going to actually be useful for,” he said, adding that he thinks AI can be useful for learning about new subjects and expediting data analysis.

Still, AI developers and tech company executives say caution is warranted.

Elon Musk said it may be time to slow down when it comes to AI, even as his social media company X rolls out the second version of its AI bot, Grok-2, which includes image generators in addition to language and sound generation.

Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, the company that makes ChatGPT, told Congress in May 2023 that government intervention would be critical to mitigating the risks of increasingly powerful AI systems.

“As this technology advances, we understand that people are anxious about how it could change the way we live. We are too,” Altman said at a U.S. Senate hearing on the advances being made in AI.

Executives of Google, Microsoft and two other companies developing AI met with Vice President Kamala Harris that same month as the Biden administration considered initiatives meant to ensure AI improves lives without putting people’s rights and safety at risk, according to the Associated Press.

“The proliferation of false material through AI, I think, is genuine concern,” said Zico Kolter, the current head of Carnegie Mellon’s Machine Learning Department. “I think it goes without saying the downside of this is not that people will believe everything. The net result is that you stop believing anything.”

Geoffrey Hinton, a British-Canadian computer scientist dubbed the “Godfather of AI,” raised eyebrows last year when he told CBC Radio in Canada, “I think that it’s conceivable that this kind of advanced intelligence could just take over from us.”

Hinton last year resigned his post at Google, where he was helping to spearhead the company’s AI technology.

“It would mean the end of people,” he said.

With AI’s connection to Carnegie Mellon, tech companies have taken root in Pittsburgh — many in a stretch in the East End nicknamed AI Avenue.

Major companies like Google have opened branch offices in Bakery Square, and new tech startups are opening their doors.

Mark Chrystal, CEO of startup Netail, is working to develop the program Profitmind to help increase retail sales and improve profits.

Retail workers tell Profitmind what the goals of the business are. The program then examines the competition and internal data and makes recommendations.

Batteries Plus, one of the companies using Profitmind, said the program makes it so the user doesn’t need extensive knowledge in economics to understand the recommendations.

“They blend the art of data with AI,” said Peter Evans, CFO of Batteries Plus.

The Profitmind chatbot allows retailers to ask questions and test pricing plans.

“The idea is not to replace the teams that are there but actually to just take a lot of the rote work off their plates and supercharge the teams to be able to capture more sales and profits,” Chrystal said.

Chrystal said he believes AI will bring a new industrial revolution.

“It’s going to change the world as much as the invention of electricity,” he said.

Another Pittsburgh company, Bloomfield.Ai, is using AI and camera images to interpret the health of farm crops.

Bloomfield.Ai CEO Mark DeSantis said the software is attached to cameras that are driven around fields of fruits and vegetables. It captures the images, assesses the crops on the vine and offers solutions to farmers.

Local investment company Walnut Capital believes Pittsburgh is primed to become the next large tech hub.

Company President Todd Reidbord and CEO Gregg Perelman are building in Bakery Square to house a variety of tech companies. They’re calling it the New Age AI Hub.

Walnut Capital has invested in more than 20 AI companies in Western Pennsylvania. In addition to Netail and Pearl Street Technologies, Walnut Capital most recently added two other companies, Lovelace Ai and Strategy Robot.

Walnut Capital’s goal is to keep adding smaller spec spaces for AI companies and to build a community of such companies that can help each other develop the technology.

Pearl Street Technologies is an example of how that can work.

Larry Pileggi, one of Pearl Street’s co-founders, also teaches at Carnegie Mellon. He and his students founded several AI-based companies. Pearl Street is trying to improve the function and reliability of the nation’s electric power grid — an idea that came from one of Pileggi’s other companies’ efforts to improve the production of computer chips.

Despite the excitement around the idea of an AI industrial revolution, public concern remains.

Chrystal tried to calm those worries.

Megan Trotter, Dinari Clacks and Haley Moreland are TribLive staff writers. You can reach Megan at mtrotter@triblive.com, Dinari at dclacks@triblive.com and Haley at hmoreland@triblive.com.